Final draft scoping report

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT FOR

THE KUSIBED DELTA AND DUNE BELT AREA

STRY OF ENVIRONM

ENT AND TOURISM,

DIRECTORATE OF ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS

NAMIBIAN

MANAGEMENT (NACOMA)

Final Draft Scoping Report

UNIVERRSITY OF NAMIBIA CENTRAL

CONSULTANCY BUREAU (UCCB)- 2011

Content List

List of Abbreviations

MGs – Matching Grants

EIA – Environmental Impact Assessment

SEA - Strategic Environmental Assessment

EMP - Environmental Management Plan

KDDP/T – Kuiseb Delta Development Project/Trust

PCO – NACOMA Project Coordinating Office

TOR – Terms of Reference

MET – Ministry of Environment and Tourism

DEA – Directorate of Environmental Affairs

CBNRM – Community-Based Natural Resources Management

NATMIRC – National Marine Information and Research Centre

ICZM – Integrated Coastal Zone Management

ORV – Off-Road Vehicles

NPC – National Planning Commission

DST – Decision Support Tool

Kuiseb Delta & Dune Belt EIA Team:

Dr Sindila Mwiya (EIA & EMP expert, DST and GIS expert):Risk-Based Solutions

Dr John Kinahan (Archaeology Study): Quaternary Research Services

Mr Peter Cunningham (Biophysical Assessment): Environment and Wildlife Consulting

Ms Margaret Angula (Socio-economic and Environmental Governance): UCCB –

University of Namibia Central Consultancy Bureau

Ms Johanna Niipele (Geomorphology & GIS): UCCB – University of Namibia Central

Consultancy Bureau

Dr Martin Hipondoka (Geomorphology & GIS): UCCB – University of Namibia Central

Consultancy Bureau

Executive Summary

1.1 Introduction

The NACOMA project under component 3 supports the management planning of coastal

biodiversity hotspots, more specifically the "Implementation of Priority Actions under the

Management Plans at site and landscape level" under sub-component 3.2. This supports

small Matching Grants (MGs) for targeted investments in specific Project intervention

sites in ecosystems of biodiversity importance. Furthermore, the NACOMA project

commissioned the undertaking of the Strategic Environmental Assessment of the

northern regions of Kunene and Erongo in 2006. The SEA strongly recommended that an

Environmental Assessment be conducted for the Dune belt area between Swakopmund

and Walvis Bay. It is against this background that NACOMA commissioned this study to

conduct an environmental impact assessment (EIA) study and develop an environmental

management plan (EMP) in reconfirming the carrying capacity of the Kuiseb Delta to

community based tourism and Dune Belt Area to various conflicting resource use

1.2 Project Location

The study area lies in the Central Namib Desert, between the Swoop River in the North

and the sand dune area south of the Kuiseb River. The Kuiseb Delta lies in an area

where the Kuiseb River flows down a steepened gradient onto the coastal flats. The Dune

Belt Area between Swakopmund and Walvis Bay is important for tourism as it creates a

number of job opportunities as part of the socio-economic development for the two

1.3 Environmental Assessment Requirements

The SEA for the Erongo Region strongly recommended an EIA be conducted in the Dune

Belt area between Walvis Bay and Swakopmund. This area is spawned by tourism and

recreational activities. The extent of impacts resulting from tourism activities is not

assessed in-depth during SEA study. Hence, it makes sense to conduct an EIA for the

entire area as recommended although the purpose of this project was initiated for the two

MGs (KDDT and Walvis Bay Bird Paradise cc).

Environmental Regulatory Framework

Important legislative instruments that affect the feasibility, operation and management of

eco-tourism activities include:

Cabinet approved Environmental Assessment Policy for Sustainable

Development and Environmental Conservation of 1995 published by the Ministry of Environment and Tourism (Directorate of Environmental Affairs (DEA), 1995;

Environmental Management Act, 2007, (Act No. 7 of 2007) - (Not yet

Water Resources Management Act, 2004, (Act No. 24 of 2004) - (Not yet

The Nature Conservation Ordinance, Ordinance 4 of 1975, Amendment Act,

Act 5 of 1996 and the draft Parks and Wildlife Management Bill of 2006;

National Waste Management Policy, 2010 National Heritage Act, 2004 (Act No. 27 of 2004) Coastal Policy for Namibia Green Paper

Other legislations, policies and regulations to be identified during the full EIA.

3. Current and Future Land Uses of the Study Area

The study area between Swakopmund and Walvis Bay is concentrated with Tourism and

recreational activities. Coastal tourism is one of the priority economic area for local,

regional and national development. Community-based tourism provides avenue to local

communities in the area (NACOMA, 2007). This area is also subject to intensive

recreational pressure during peak holidays (NACOMA, 2004). There are also other

activities in the area, such as quad-biking, cultural, sightseeing and eco-tours operating in

the study area. The nature of these activities prompted this EIA study commissioned by

Description of the Proposed Project

There are two proposed projects that received Matching Grant funding from NACOMA

PCO. These projects are proposing community-based eco-tourism activities. The Kuiseb

Delta Development Trust applied for a concession from MET and engage in Community

Based Tourism activities. The Walvis Bay Bird Paradise proposes to establish a bird

watching tourism activity. There are also other activities in the area, such as quad-biking,

cultural, sightseeing and eco-tours operating in the study area. The nature of these

activities prompted this EIA study commissioned by NACOMA PCO.

Baseline Environment

This section presents the description of the natural environment that may be affected by

activities proposed in the study area. The Central Namib near the coast has a

temperature range that is moderated by proximity to the sea. The average precipitation

(fog and rain) ranges around 15mm at the coast. The wind at the coastal areas of

Namibia is characterised by strong southerly winds but westerly and south westerly winds

are also frequent. The area is characterised by four distinct geomorphological units. The

largest by far is the dune field. Other units include inter-dune plains, gravel/ coastal plain,

river beds and delta. Sufficient good quality groundwater is available for different land

users in the coastal towns.

The literature review was undertaken to determine the actual as well as potential

vertebrate fauna associated with the general area commonly referred to as the Southern

Namib or Southern Desert. This area is bordered inland by the Central Namib or Central

Desert. Climatically the coastal area is referred to as Cool Desert with a high occurrence

of fog. The Namib Desert Biome makes up a large proportion (32%) of the land area of

Namibia with parks in this biome making up 69% of the protected area network or 29.7%

of the biome. Four of 14 desert vegetation types are adequately protected with up to 94%

representation in the protected area network in Namibia. With the exception of municipal

land, the area falls within the recently proclaimed Dorob National Park. No communal

and freehold conservancies are located in the general area with the closest communal

conservancy being the ≠Gaingu Conservancy in the Spitzkoppe area approximately 100

km to the northeast. Two important coastal wetlands – i.e. Walvis Bay Wetlands and

Sandwich Harbour – both Ramsar sites, occur in the area. According to Curtis and

Barnard (1998) the entire coast and the Walvis Bay lagoon as a coastal wetland, are

viewed as sites with special ecological importance in Namibia. The known distinctive

values along the coastline are its biotic richness (arachnids, birds and lichens) with the

Walvis Bay lagoon‟s importance being its biotic richness and migrant shorebirds as well

as being the most important Ramsar site in Namibia. The Ramsar site covers 12 600 ha

with regular counts of birds varying between 37 000 and well over 100 000 individuals,

albeit mainly migratory species. The Walvis Bay wetland is considered the most

important coastal wetland in southern Africa and one of the top 3 in Africa. The Sandwich

Harbour Ramsar site covers 16 500 ha and falls within the Namib-Naukluft Park and

enjoys full protection. This area is a centre of concentration of migratory shorebirds,

waders and flamingos regularly supporting over 142 000 and 50 000 birds during summer

and winter, respectively. The area is bordered by the Kuiseb River to the south (Walvis

Bay area) and the Swakop River to the north (Swakopmund area) with catchment areas

of 15 500 km² and 30 100 km², respectively. The central coastal region and the Walvis

Bay area in particular, is regarded as "relatively low" in overall (all terrestrial species)

diversity. Overall terrestrial endemism in the area on the other hand is "moderate to

high". The overall diversity and abundance of large herbivorous mammals (big game) is

viewed as "low to medium" with 1-2 species while overall diversity of large carnivorous

mammals (large predators) is determined at 4 species with brown hyena being the most

important with "medium" densities expected in the area. It is estimated that at least 54

reptile, 7 amphibian, 42 mammal and 182 bird species (breeding residents) are known to

or expected to occur in the general/immediate Walvis Bay/Swakopmund area of which a

high proportion are endemics.

6. Scoping Study Conclusions

Coastal tourism is a priority economic area for local, regional and national development.

Community-based tourism activities can provide employment but they are also likely to

cause social and environmental impact. Biological hotspots, breeding areas,

environmental sensitive areas may suffer from uncontrolled tourism development and

activities. These impacts however can be effectively mitigated through careful planning

and design of sustainable tourism activities.

Scoping Study Recommendations

Full Environmental Assessment

Based on the findings of the scoping study it is recommended that a full EIA and the

development of an EMP be undertaken for the proposed eco-tourism and recreational

activities in the Kuiseb Delta and Dune Belt area. Draft TOR for the full EIA and EMP

include the list of stakeholders, specialist studies to be undertaken, likely positive and

negative impacts to be considered as well as draft proposed outline of the EIA and EMP

Aims and Objectives of the Full Environmental Assessment (EA)

The aims and objectives of the full EIA and EMP with respect to the proposed eco-

tourism activities in the Kuiseb and Dune Belt areas are:

To assess all likely positive and negative impacts environmental and social

impacts on the local and regional (Erongo Region) and national (Namibia) using

appropriate assessments guidelines, methods and techniques covering the

complete project cycle. The EIA and EMP shall be performed in accordance and

conforming to national regulatory requirements, process and specifications in

Namibia and in particular Ministry of Environment and Tourism and the Namibian

Tourism Board as well as draft guidelines for conducting EIA & EMP (MET/DEA,

The development of appropriate mitigation of appropriate measures that will

enhance the positive impacts and reduce the likely negative impacts anticipated or

Stakeholders‟ participation in the EIA process is a critical component in achieving

transparent decision-making. Stakeholders‟ involvement in the EIA process gives all

interested and affected parties such as local communities and individuals a voice in

issues that may bear directly on their health, welfare, and quality of life. An open flow of

environmental information can foster objective consideration of the full range of issues

involved in project planning and can allow communities and citizens to make reasoned

choices about the benefits and risks of proposed actions (MET/DEA, 20008).

A number of interviews and workshops will be conducted with the members of the local

communities and any other stakeholders particularly in Walvis Bay and Institutions from

Swakopmund and Walvis Bay. Consultations with stakeholders will cover the following:

- Awareness about the proposed projects

- Expectations of local communities in terms of temporal and permanent

contracts/job opportunities as well as local economic benefits

- Worries and concerns of farmers and existing tour operators in Kuiseb Delta and

- Views of the various stakeholders, particularly the local communities of Walvis

Bay, with respect to the likely positive and negative impacts of the proposed

project on the environment and suggestions on the appropriate mitigation

The following is the provisional list of identified interested and affected stakeholders who

will be contacted for input/comments to the EIA process:

- MET/DEA/NACOMA

- MET – Parks, CBNRM, Tourism

- Roads Authority

- Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources (NATMIRC)

- Ministry of Regional Local Government Housing and Rural Development

- Erongo Regional Council

- Namibia Wildlife Resorts

- Namibia Tourism Boards

- KDDT and Boards of Trustees

- Topnaars community in the Kuiseb Delta

- Walvis Bay Bird Paradise Caretaker

- Traditional authority

- Coastal Tour Operators Association

- Coastal Environment Trust of Namibia

- Lauberville – in the Kuiseb Delta

- National Heritage Council of Namibia

- Fishing Companies and NamPort (those involved with Topnaars community)

- 18 Tour operators and agencies are identified (Having stake in the KDDT)

- Rossing Foundation/Rio Tinto

- NGOMA Consulting Services

- Local and Tour Operator Organisations and representatives

- Walvis Bay Municipality

- Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Forestry

- National Botanical Research Institute

- Other stakeholders to be identified during newspaper advertisement and to be

registered and reflected in the Final EIA report

Specialist Studies to be Undertaken

The specialist studies identified during scoping will be undertaken by specialist

consultants and the results of these studies will comprise the full EIA and EMP reports.

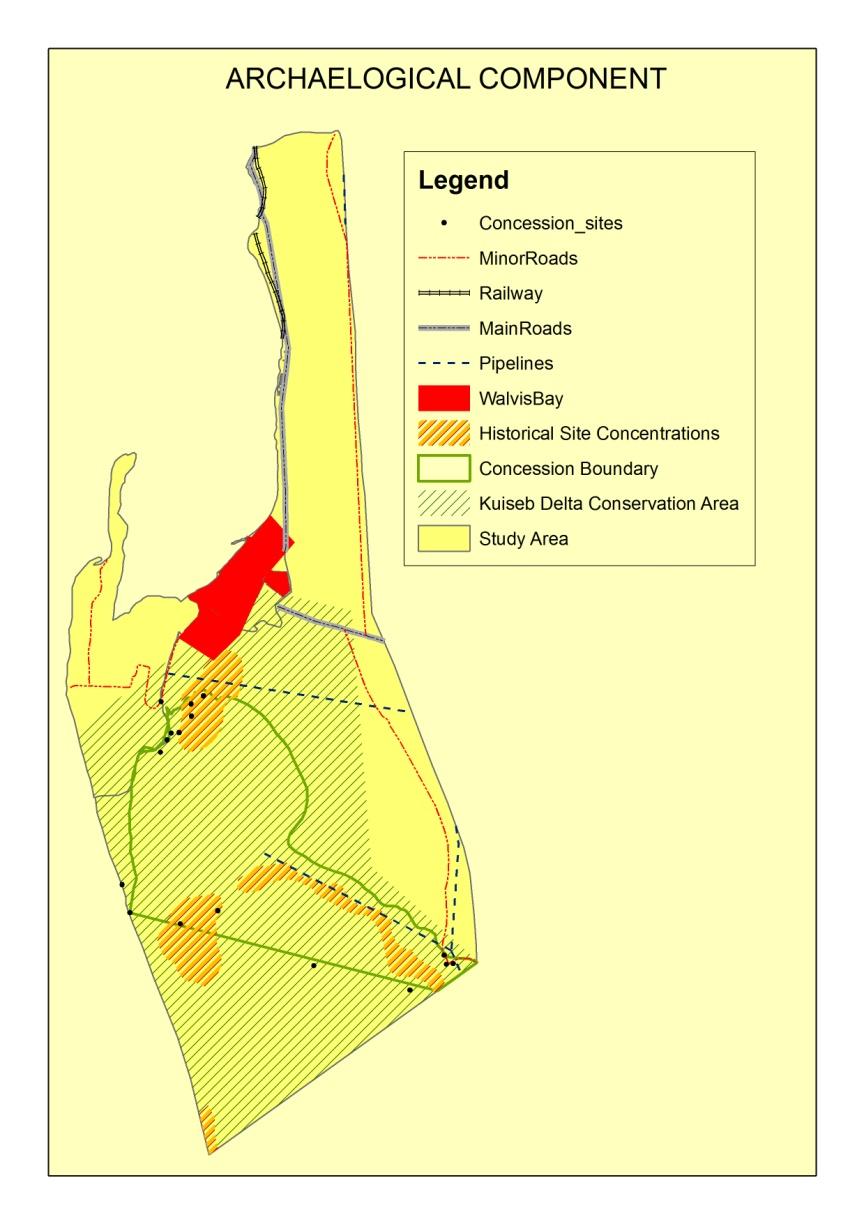

The Archaeology study (Dr John Kinahan)

The Vertebrate Fauna and Flora study (Mr Peter Cunningham)

Geomorphology Study (Dr Martin Hipondoka)

Likely Positive Impacts to be Considered

The following is the summary of the likely positive impacts that will be assessed at

different levels of the proposed solar energy project developmental stages;

Local and Regional social, economic, and cultural impacts;

Opportunities for community participation;

Other issues to be identified during the consultation process.

Likely Negative Impacts to be Considered

The following is the summary of the likely negative impacts that will be assessed at different levels of the proposed solar energy project developmental stages;

Current and future land uses, zonation and existing infrastructures and

Threats to biodiversity (habitat alteration and species injury or mortality and

Visual impacts, Water use and quality;

Waste and Sewage management at project sites ;

Wind situation;

Tourism activities and quad-biking

Other issues to be identified during the consultation and full Environmental

Assessment process.

Environmental Management Plan (EMP) Considerations

The following is the summary of the likely EMP considerations that will be assessed

based on the findings of the EIA:

- Waste and sewerage management

- Wind situation

- Tourism carrying capacity

- Facilities and structures at project sites

- Historic and Archaeology sites

- Implementation of the EMP

- Environmental Awareness and Training

- Off-road Vehicle zones, access and driving

- Tour activities (e.g. hiking and driving trials, archaeology, historical and cultural

- Dealing with Environmental Complaints Guidance

Proposed Outline of EIA and EMP Reports

The following is the summary of the tentative content lists of EIA, EMP and Final Scoping

(Baseline) reports:

VOLUME 1 or Part 1: Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA)

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

PROJECT BACKGROUND

POLICY, LEGAL, AND ADMINISTRATIVE FRAMEWORK

DETAILED PROJECT DESCRIPTION

SOCIO-ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT

NATURAL ENVIRONMENTS

(viii) ASSESSMENT OF LIKELY ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS

ANALYSIS OF ALTERNATIVES

EIA CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

VOLUME 2 OR PART 2: ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN (EMP)

INTRODUCTION TO THE EMP

ENVIRONMENTAL POLICIES

OBJECTIVES OF THE EMP

THE EMP FRAMEWORK

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE EMP

ENVIRONMENTAL MONITORING PLAN

ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT AND TRAINING

(viii) APPENDICES

VOLUME 3 OR PART 3: FINAL SCOPING REPORT

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

PROJECT BACKGROUND

ENVIRONMENTAL REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

DESCRIPTION OF PROPOSED PROJECTS

BASELINE ENVIRONMENT

HERITAGE RESOURCES

SOCIO-ECONOMIC ENVIRONMENT

(viii) GEOLOGICAL SETTINGS

ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

PROJECT BACKGROUND

1.1 Introduction

The Namibian Coast Conservation and Management (NACOMA) project is a multi-

sectoral national initiative that is aimed at enhancing coastal and marine biodiversity

conservation through the mainstreaming of biodiversity conservation and sustainable use

into coastal policy, legislative framework, and institutional and technical capacity. The

NACOMA project is supporting four components addressing legislation, capacity building,

sustainable investments and performance monitoring for Integrated Coastal Zone

Management (ICZM).

The NACOMA project under component 3 supports the management planning of coastal

biodiversity hotspots, more specifically the "Implementation of Priority Actions under the

Management Plans at site and landscape level" under sub-component 3.2. This supports

small Matching Grants (MGs) for targeted investments in specific Project intervention

sites in ecosystems of biodiversity importance. As such, the Kuiseb Delta Community and

investors from Walvis Bay and Swakopmund were awarded small Matching Grants to

invest in projects that support sustainable development. These MG‟s proposed activities

that require an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) study. Furthermore, the

NACOMA project commissioned the undertaking of the Strategic Environmental

Assessment of the northern regions of Kunene and Erongo in 2006. The SEA strongly

recommended that an Environmental Assessment be conducted for the Dune belt area

between Swakopmund and Walvis Bay. It is against this background that NACOMA

commissioned this study to conduct an environmental impact assessment (EIA) study

and develop an environmental management plan (EMP) in reconfirming the carrying

capacity of the Kuiseb Delta to community based tourism and Dune Belt Area to various

conflicting resource use activities.

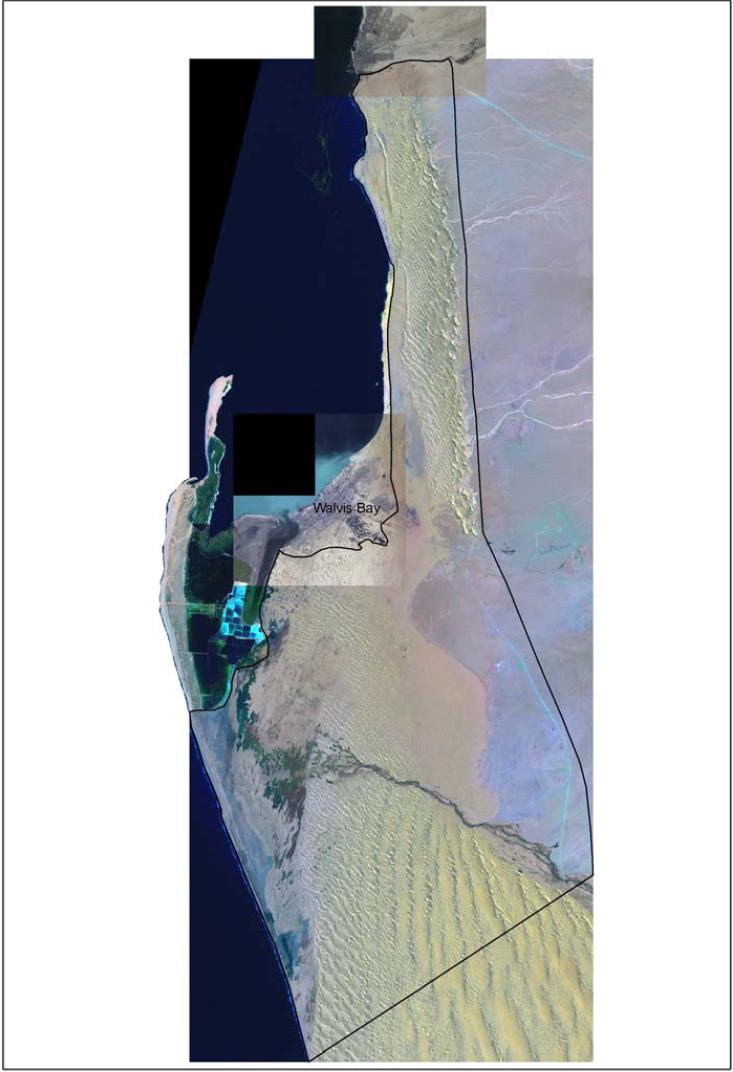

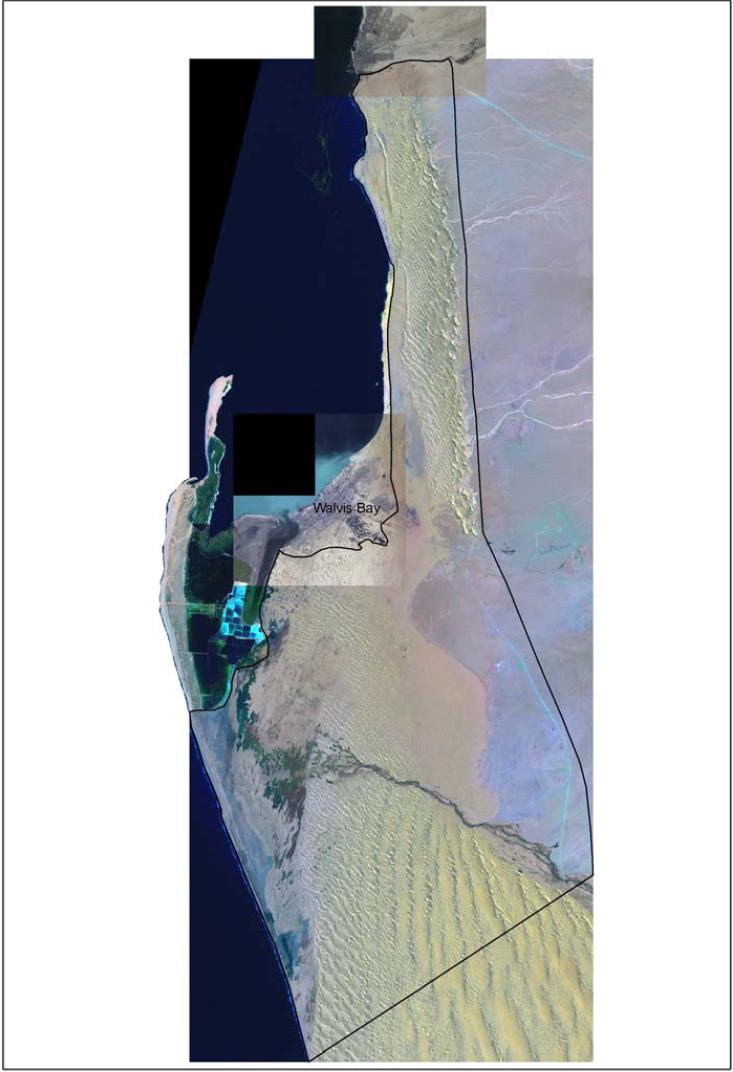

1.2 Project Location

The study area lies in the Central Namib Desert, between the Swakop River in the North

and the sand dune area south of the Kuiseb River. The area has a considerably high

variation of the natural environment and climatic patterns (InnoWind Draft Scoping

Baseline Report, 2010) influenced by the position of the high-pressure cells over the

South Atlantic Ocean which creates arid and semiarid conditions on the west coast of

Africa, (Svendsen et al., 2007).

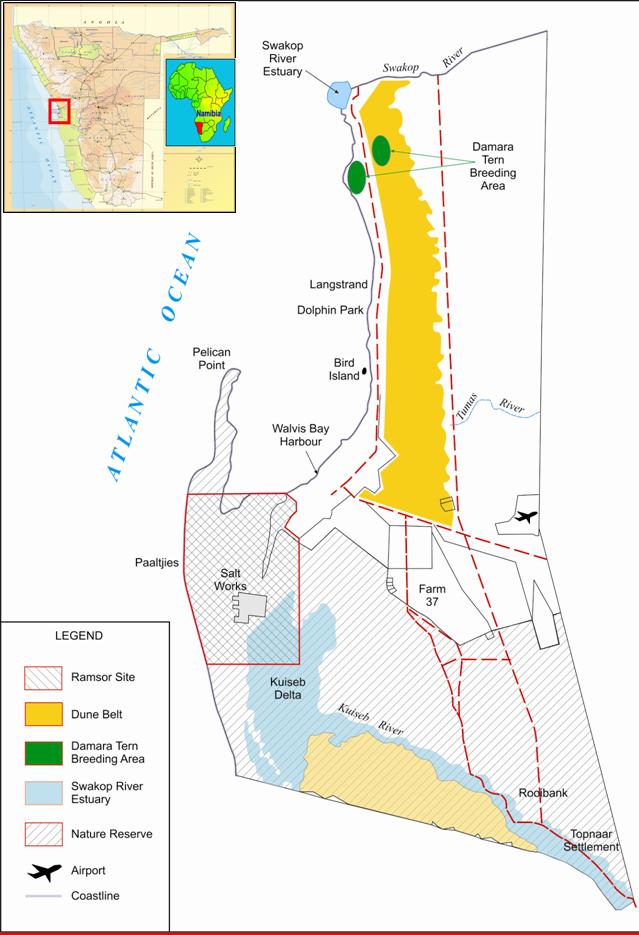

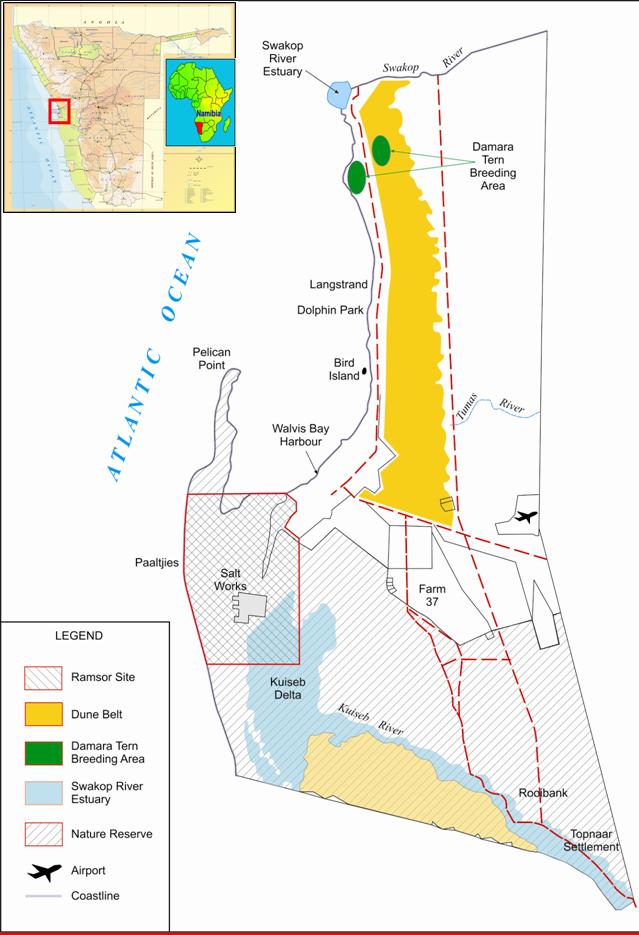

1.2.1 The Kuiseb Delta

The Delta lies in an area where the Kuiseb River flows down a steepened gradient onto

the coastal flats (Figure 1.1). The delta is made up of a series of channels and palaeo-

channels forming an intricate network of fine-grained fluvial deposits associated with

numerous small aeolian dunes South-east of Walvis Bay (Ninham Shand Consulting

Services, 2008).

In the previous SEA study under the Namibia Coast Conservation Management Project

(NACOMA), the Kuiseb Delta has been classified as an area of very high conservation

priority falling under the Walvis Bay Nature Reserve Management Plan, in line with the

new Wetland Policy. The study suggested that the Ministry of Environment and Tourism

(MET) should formally designate the Nature Reserve as a protected area. MET, the

Walvis Bay Municipality and the Coastal Environmental Trust of Namibia should ensure

further enforcement of the national Wetland Policy in the area by adopting the Nature

Reserve Management Plan. Furthermore, they should also establish a long-term

environmental monitoring programme which should include the biodiversity elements for

terrestrial, coastal and offshore habitats found in the wetland. They also suggested that

the information derived from the monitoring programme should feed into the requirement

for improved Environmental Impact Assessments. To make full use of the potential for

development of eco-tourism and traditional tourism in the wetland, a tourism development

plan for the Nature Reserve should be drafted by the Walvis Bay Municipality in

collaboration with the Walvis Bay Tourism Association and the Marine Tour Association of

Namibia. Developments of all tourist activities and accommodation facilities should occur

on the basis of permissions subject to Environmental Impact Assessment, (MET/DEA,

1.2.2. Dune belt area

The Dune Belt Area between Swakopmund and Walvis Bay (Figure 1.1) is important for

tourism as it creates a number of job opportunities as part of the socio-economic

development for the two coastal towns. The area is characterised by a unique landscape

of different types of dunes and gravel plains as well as a unique biodiversity, which is of

conservation importance. Due to the water scarcity and low annual rainfall, the rate of

vegetation growth is very slow and requires a long period of time to recover from

The dunes and gravel plains between Walvis Bay and the Kuiseb River, as well as south

of the Kuiseb River include a variety of desert landscapes. Most outstanding are the

various types of sand dunes which take on mainly crescent-shaped forms. The gravel

plains are less spectacular but represent a natural part of the desert landscape around

Walvis Bay as the windswept part of the desert. The gravel plains are rich in stones and

minerals of a very high diversity and form an extremely sensitive desert pavement,

As per Cabinet decision, the dune belt area currently managed by MET, should be

included in the Walvis Bay Nature Reserve, and free zones for off-road driving should be

maintained east of Walvis Bay and east of Long Beach. The demarcation of the free zone

east of Long Beach should take into account the area south of the settlement, used for

breeding purposes by Damara Tern birds. The management and environmental

monitoring of the area should be part of the activities proposed for the Nature Reserve

and the expansion of eco-tourism activities should be promoted through inclusion of the

dune belt in the proposed Walvis Bay tourism development plan. Cabinet decision also

suggested that prospecting or mining licences should not be granted in the dune belt

once the existing licences expire and that the zoning of eco-tourism and free zones for

off-road driving should become object of a detailed Environmental Impact Assessment,

nd (MET/DEA, 2008).

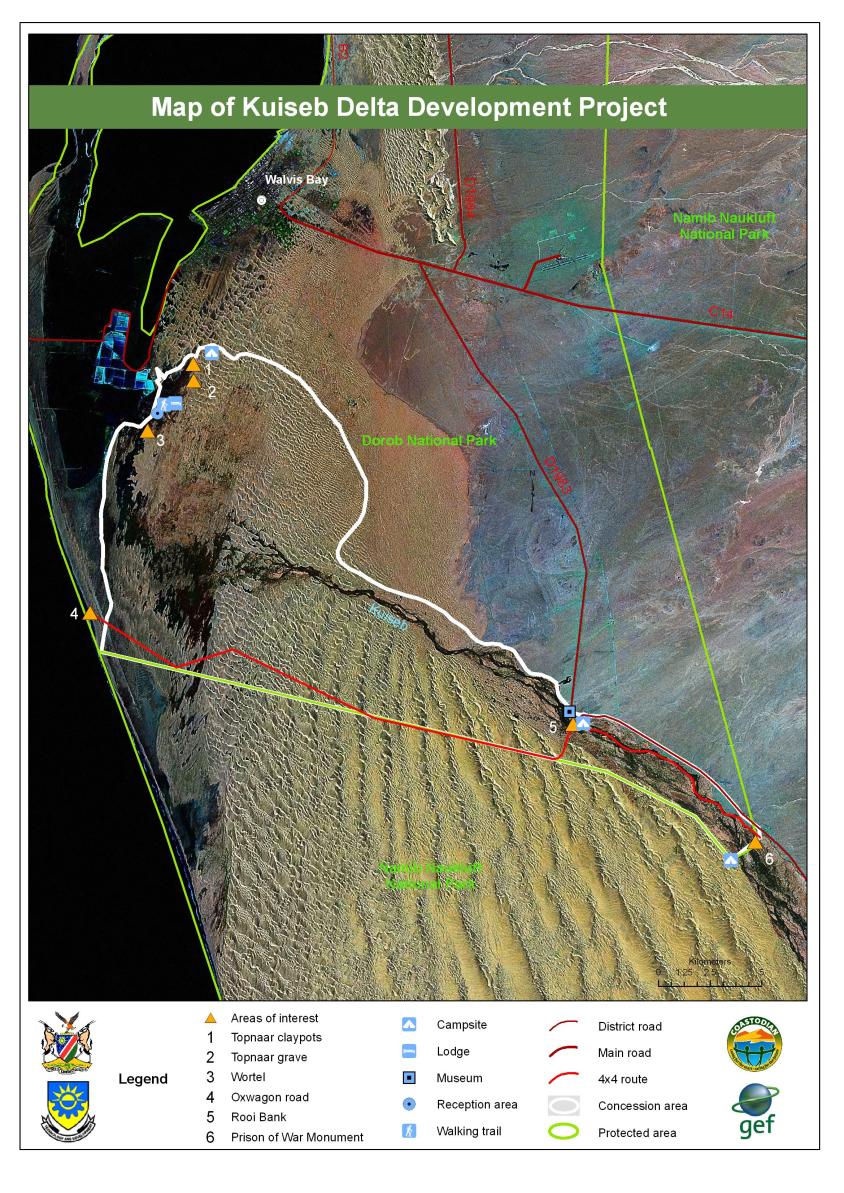

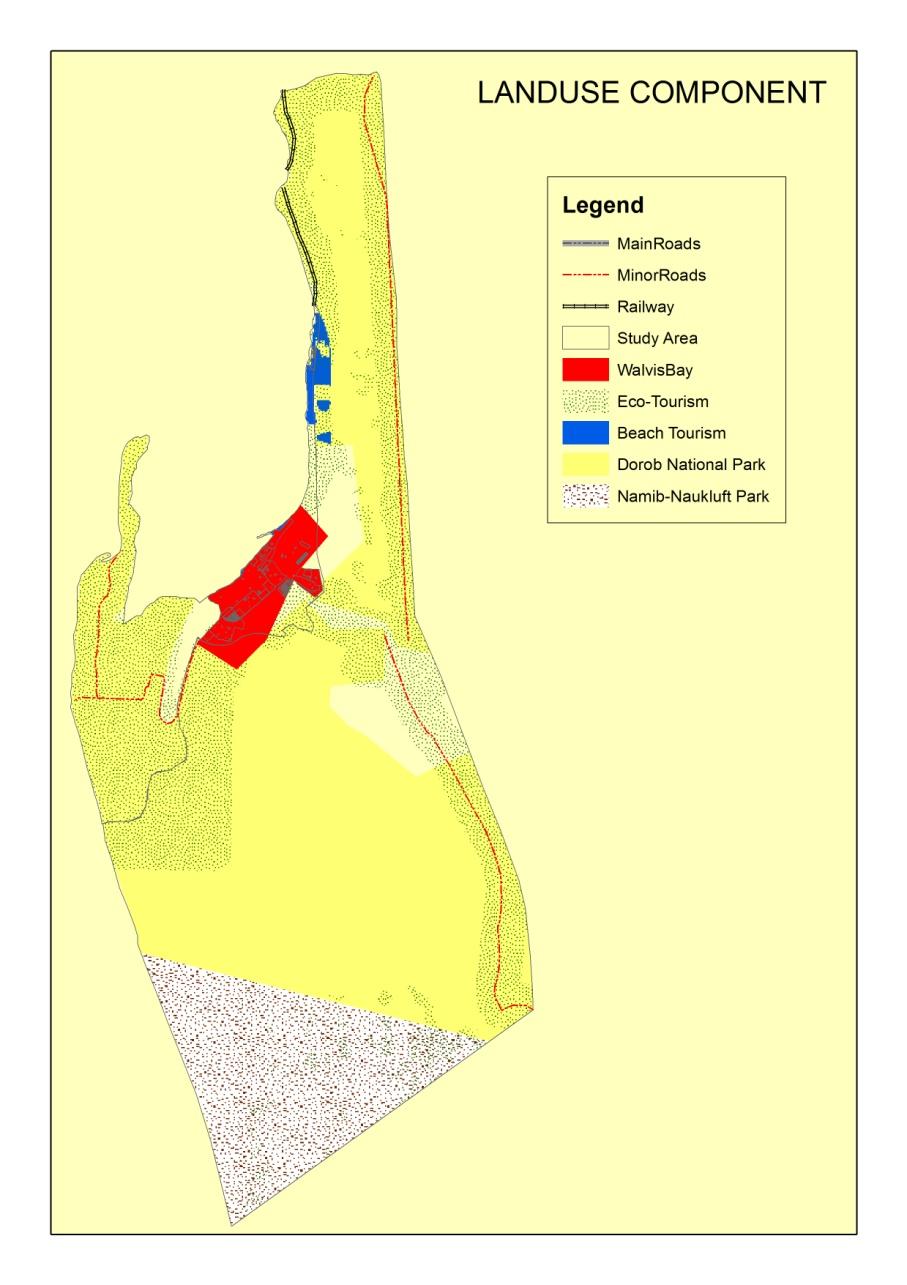

Figure 2.1 1.1: Project Location

1.3 Environmental Assessment Requirements

As explained earlier, the SEA strongly recommended an EIA be conducted in the Dune

Belt area between Walvis Bay and Swakopmund. This area is spawned by tourism and

recreational activities. The extent of impacts resulting from tourism activities is not

assessed in-depth during SEA study. Hence, it makes sense to conduct an EIA for the

entire area as recommended although the purpose of this project was initiated for the two

MGs (KDDT and Walvis Bay Bird Paradise cc).

This project conform to the Environmental Assessment Policy for Sustainable,

Development and Environmental Conservation (1995), Environmental Management Act,

2007 (Act No.7 of 2007) and the Draft Procedures and guidelines for EIA & EMP of 2008.

In accordance with the Policy on Tourism and Wildlife Concessions on State Land,

proposed tourism activities in the Kuiseb Delta and Dune Belt area are required to

undertake an EIA study. In accordance with the Environmental Management Act, 2007

(Act No.7 of 2007), the Environmental Study shall include (i) Scoping (Baseline report) (ii)

Environmental Impact Assessment and (iii) development of an Environmental

management Plan. The framework for conducting the EA is explained in the following

reports (SAIEA, 2003, Republic of Namibia, 2008 & Republic of Namibia, 1995) and the

illustration is shown in Figure 1.2 below:

Figure 2.1 1.2: Environmental Assessment process in Namibia (Directorate of

Environmental Affairs, 2008).

1.4 Purpose of this Scoping (Baseline) Study

This scoping report is prepared for the EIA of the Kuiseb Delta, Walvis Bay sewerage

ponds and Dune Belt Area in the coastal are of the Dorob National Park, Erongo Region.

The objective of scoping study is to identify from a broad range of potential problems, a

number of key issues of concern that should be addressed by an EIA. Scoping also assist

in identification of information sources and data gaps that may require to be filled by

specialists studies. Therefore, this phase of assessment determines the key elements of

the Environmental Management Plan (EMP) for the Kuiseb Delta, Walvis Bay sewerage

ponds and Dune Belt area.

The output of this scoping exercise contained in this report includes:

Description of existing, proposed and potential activities A preliminary list of reasonable alternatives to be considered in the EIA Identification of laws and guidelines that have been considered in the preparation

of the scoping report

Description of physical, biological, cultural, social and economic environment that

may be affected by proposed tourism activities in the study area

Description of environmental issues and potential impacts, including cumulative

impacts that have been identified

An inventory of stakeholders likely to be consulted

ENVIRONMENTAL REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

2.1 Introduction

The study area was previously known as a National West Coast Recreational area. As

such most activities are geared towards recreational, leisure and non-consumptive

tourism. In addition, the Kuiseb Delta, Walvis Bay sewerage ponds and Dune Belt area

are situated within the newly proclaimed Dorob National Park. Therefore, tourism and

nature conservation activities fall within jurisdiction of the Ministry of Environment and

Tourism with environmental regulations guided by the Directorate of Environmental

Affairs, within the same ministry.

Although, the Environmental Management Act, 2007 (Act No.7 of 2007) and procedures

and guidelines for the EIA and EMP are not yet implemented, they provided the

framework followed by the process of developing the baseline report and an EIA study.

However, the study followed the legal framework provided by the Environmental Impact

Assessment Policy, 1995. The legislation of the Republic of Namibia that are relevant for

this study and has been consulted for the scoping study are listed in section 2.2 as

presented below.

2.2 Environmental Regulations

2.2.1 Constitution of the Republic of Namibia (1990)

The constitution commits the Government of Namibia to sustainable utilisation of

Namibia‟s natural resources for the benefit of all Namibians. Article 95 of the constitution

states that "the State shall actively promote and maintain the welfare of the people by

adopting, inter alia, policies aimed at maintenance of ecosystems, essential ecological

processes and biological diversity of Namibia and utilisation of natural resources on a

sustainable basis for the benefit of all Namibians both present and future"

2.2.2 Environmental Management Act, 2007 (Act No.7 of 2007)

The Environmental Management Act of Namibia is not yet implemented, nevertheless it

provide legal framework necessary for the guidance of the scoping and EIA studies.

Accordingly, the act will give legislative effect to the EIA Policy; allow establishment of the

Sustainable Development Advisory Council and appointment of the Environmental

Commissioner. Such institutions are expected to improve the management of impact

assessment in Namibia. With regard to this study, the act gives directives to developers

to gain clearance from the Environmental Commissioner before proceeding with plans.

The functions of the Environmental Commissioner are currently carried out by the

Environmental Assessment Unit of DEA/MET.

2.2.3 Environmental Assessment Policy

The essence of the EIA policy is the principle of achieving and maintaining sustainable

development. In it, all policies, programmes and projects undertaken within Namibia shall

be guided by sustainable development principles. The Environmental Assessment Policy

requires require full EIA to be submitted to the Ministry of Environment and Tourism for

commercial tourism and recreation facilities. As such, proponents are required to follow

the integrated environmental management procedure set out in the policy.

2.3 Other Specific Legislation

2.3.1 Nature Conservation legislation

Nature Conservation Ordinance amendment Act, Act 5 of 1996 progressed from the old

South African Nature Conservation Ordinance, Ordinance 4 of 1975. The Amendment act

provides for community based natural resource management. The Draft Parks and

Wildlife Management Bill is anticipated to replace the Nature Conservation Ordinance

amendment Act, Act 5 of 1996. The state protected areas are governed by the amended

2.3.2 Tourism

The National Policy on Tourism for Namibia, 2008 aims to provide a framework for the

mobilisation of tourism resources to realise long term national goals defined in Vision

2030 and specific targets of the NDP3, namely, sustained economic growth, employment

creation, reduced inequalities in income, gender as well as between the various regions,

reduced poverty and the promotion of economic empowerment.

2.3.3 National Heritage Act

The National Heritage Act provides for the preservation and registration of places and

objects of national significance. Moreover, it establishes a National Heritage Council and

a National Heritage Register.

2.3.4 Water Resource Management and Regulations

The Water Act, Act No. 54 of 1956 inherited from South Africa is still in force because the

National Water Resource Act, Act No. 24 of 2004 is not yet promulgated. The Act makes

provision for a number of functions pertaining to control and use of water resources,

water supply and protection of water resources. Once the National Water Act of 2004 is

promulgated it will provide specific procedures for water abstraction permitting that are

much more adapted to Namibia‟s climate and geohydrology than the Water Act of 1956.

2.3.5 Waste Management

The essence of the National Waste Management Policy, 2010 is to prevent and reduce

health risks associated with exposure to healthcare substances, household, radiation and

other waste from healthcare workers, waste handlers and public by promoting sound

environmental waste management practices. In addition, to design appropriate means of

safe and sustainable waste management. In order to achieve lasting positive impact on

health and environment, any new program should be subjected to sustainability

assessment before implementation.

2.3.6 Coastal Policy for Namibia (Green Paper, Feb 2009)

The Coastal Policy Green Paper is a background document which sets the overall

framework for development in the coastal area. As such it sets out, firstly, the coastal

policy process. As with other legislation that are not yet in force, the study will consider

green paper coastal policy.

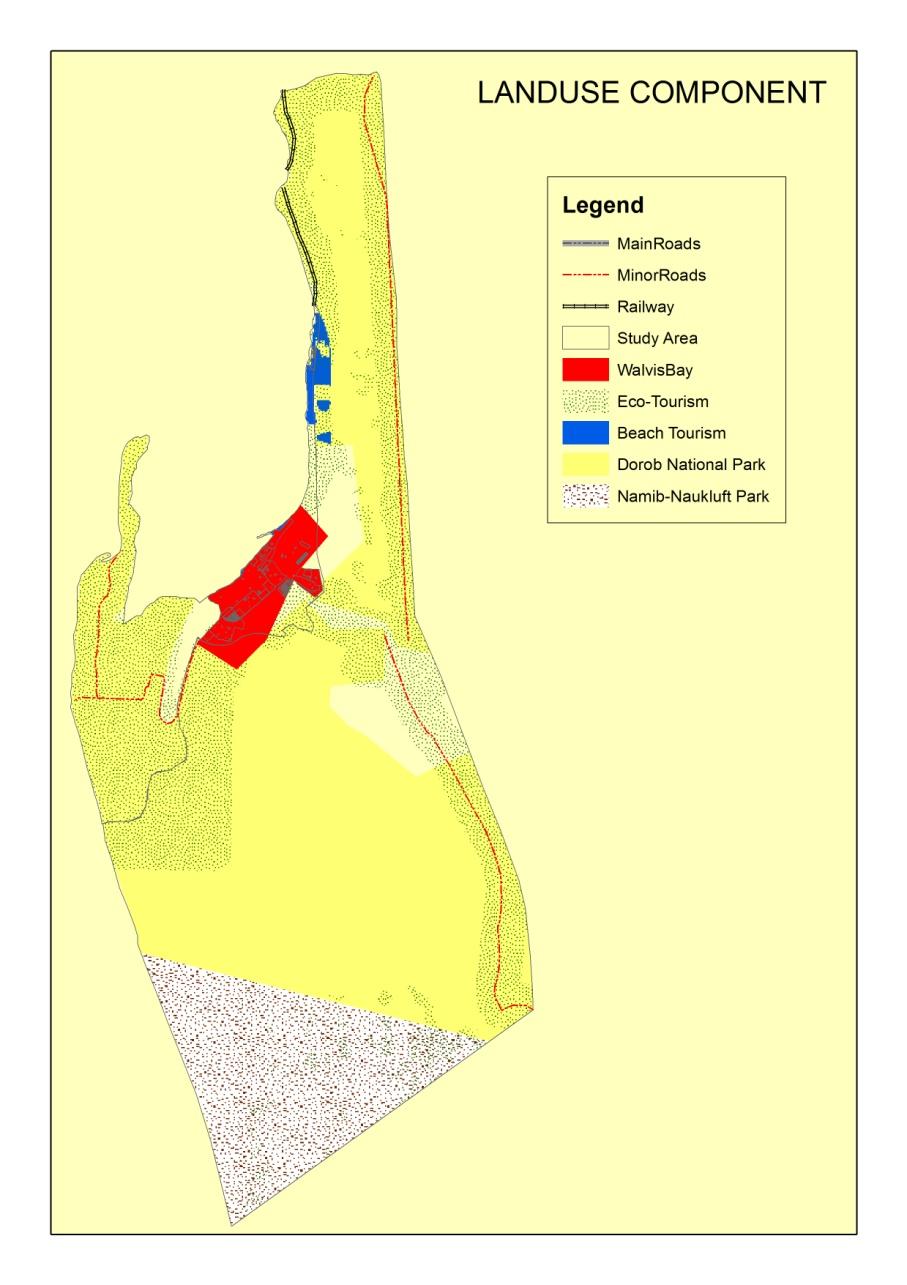

3. Current and future land uses of the study

Erongo Region is one of the most economically active regions in the country. Its'

economy rely heavily on Fisheries, Mining and Tourism. The study area between

Swakopmund and Walvis Bay is concentrated with Tourism and recreational activities.

Coastal tourism is one of the priority economic area for local, regional and national

development. Community-based tourism provides avenue to local communities in the

area (NACOMA, 2007). This area is also subject to intensive recreational pressure during

peak holidays (NACOMA, 2004).

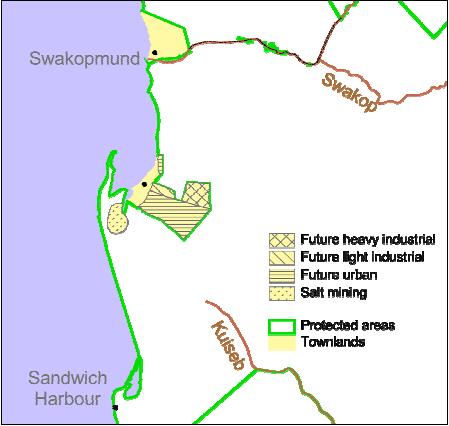

The current EIA study excludes townlands of Swakopmund and Walvis Bay as well as

industrial areas between the towns. Nevertheless, NACOMA (2009) published in its

management plan for the central coast park of the Namib-Skeleton coast national park.

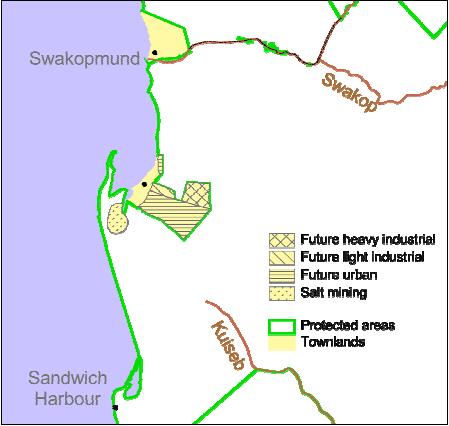

These areas are shown in Figure 2.1 below:

Figure 3.1 Future areas of infrastructure growth in the southern central coast area

(NACOMA, 2009:47)

3.1 Current and future tourism activities in the Kuiseb Delta and

Dune Belt area

According to the BGR (2008) tourism products in the area include adventure tourism,

business tourism, non-consumptive tourism and ecotourism. As such, the Dune belt area

is the only coastal dune area that is easily accessible to the public (NACOMA, 2004). In

itself, the area is important for multiple tourism use practices in the tour operator sector.

The area also contains a diversity of biophysical features and attractive landscape. Land-

based and nature-based tourism activities in the study area are included in itinerary for

trips from the coast into Kunene region, notably Twyfelfontein (NACOMA, 2007). Figure

2.2 below illustrates current land-use zones in the study area.

Figure 3.2: Current Land use zones in the study area

The following tourism and recreational activities are identified by (NACOMA, 2007) and

NACOMA (2009) studies (refer to Figure 1.5 below):

Desert tours Sightseeing trips Tours to Dune 7 Dune-boarding Quad biking 4X4 Off-road recreational driving Paragliding Scenic flights Filming and Photography Weddings, desert tented bouquets, picnics, annual 4x4 vasbyt events Walking, hiking and horse riding

Figure 3.3 : Tourism Business and Recreational Areas in the Dune Belt area

(NACOMA, 2009:42, 43 & 46)

As explained earlier, the KDDP and Trust was only established during 2009/10.

Therefore, unregulated tourism activities have been taking place in the Delta over the

past years. However, there are some regulated tourism-based activities led by Topnaars

community. The following activities are currently taking place in the Delta (Mufita, 2011

- Tour guide: 4x4 vehicles and quad bikes off-road driving,

- Walking trials, hiking and sand boarding

- Scenic Flights

- Tour operators marketing self-touring products in their itinerary

3.2 Sub Regional Concepts

The sub-regional concept of Walvis Bay as outlined in, provides for demarcation of

defined zones to accommodate existing and future land uses. The following is an extract

summary from the sub-regional concept document for Walvis Bay outlining the various

zones (see also, Figure 3.1 above & Figure 3.4 Below):

Figure 3.4 : Regional Location

Walvis Bay Nature Reserve: The zone is on the southern part of Walvis Bay,

roughly from the southern edges of Farms 29, 37 and 38 to the Kuiseb River.

The Lagoon, the Salt-Works and the Topnaar community settlement are

located in this zone… Since this zone is ecologically fragile, in such a way that

it supports unique and fascinating ecological communities, it is recommended

to be left free of any development other than those relating to cultural and eco-

tourism and/or aqua-culture/agriculture. All existing developments located in

this area should continue their activities in this area. However, new applications

of such kind will not be allowed;

Conservation: This area includes Farms owned by Council, part of the

coastline between Walvis Bay and Swakopmund, part of the dune belt and the

area immediately adjacent to the Swakop River Bed…Activities relating to

environmental conservation education, and/or eco-tourism. Off road vehicles

are prohibited in this area. Quad bikes and all other off road vehicles are not

allowed in this zone;

Recreation: Five areas are demarcated as recreation zones: South of the

Swakop River, East of Long Beach, North – West of the Tumas River, Dune 7,

and the coastline along Long Beach and Dolphin Park. Quad bikes as well as

all other off road vehicles will only be accommodated in the dunefield part of

this zone. All off road vehicles are to be led into the dunes via fixed tracks.

Quad bikes are prohibited in the beach area (i.e. the coastline along Long

Beach/Dolphin Park) of the recreation zone;

Industrial: The zone comprises of the areas demarcated for the heavy

industrial development behind the dune belt. Noxious and nuisance creating

industries should be located in this area;

Government: The zone is bounded by the Tumas River on the South and the

gravel road between Walvis Bay and Swakopmund on the West… Zone 5 will

permit only military related activities;

Land for Development: This includes the area just south of the Airport and

Dune 7 and South-East of the „built-up urban area‟ as well as the Long

Beach/Dolphin Park development. The node at Long Beach/Dolphin Park can

be strengthened. Developments at Long Beach/Dolphin Park have to abide to

this policy…With the exception of the Long Beach/Dolphin Park development,

any other proposed development in this area should be: scattered, not

agglomerated, to allow the dominant presence of the desert to be maintained,

and are subject to an Environmental Impact Assessment.

DESCRIPTION OF THE PROPOSED PROJECT

4.1 General Overview

Through the NACOMA Project Co-ordinating Office (PCO) and the Steering Committee, a

number of investment proposals were approved for implementation under the World Bank

Matching Grant support. The NACOMA Project Sub-component 3.2 is concerned with

provision of technical support and small matching grants for targeted investments in

specific project intervention sites. Kuiseb Delta Development Trust (KDDT) and Walvis

Bay Bird Paradise were among approved proposals and MG‟s recipients. Part of the

technical support is to identify activities to be funded through the NACOMA MG, to

facilitate a feasibility study and carry out an EIA screening to determine if there are

significant or no significant impacts requiring an assessment. However, the scope of this

consultancy is to also focus on other activities currently operating in the area as well as

identify potential eco-tourism and recreational activities in the Kuiseb Delta and Dune Belt

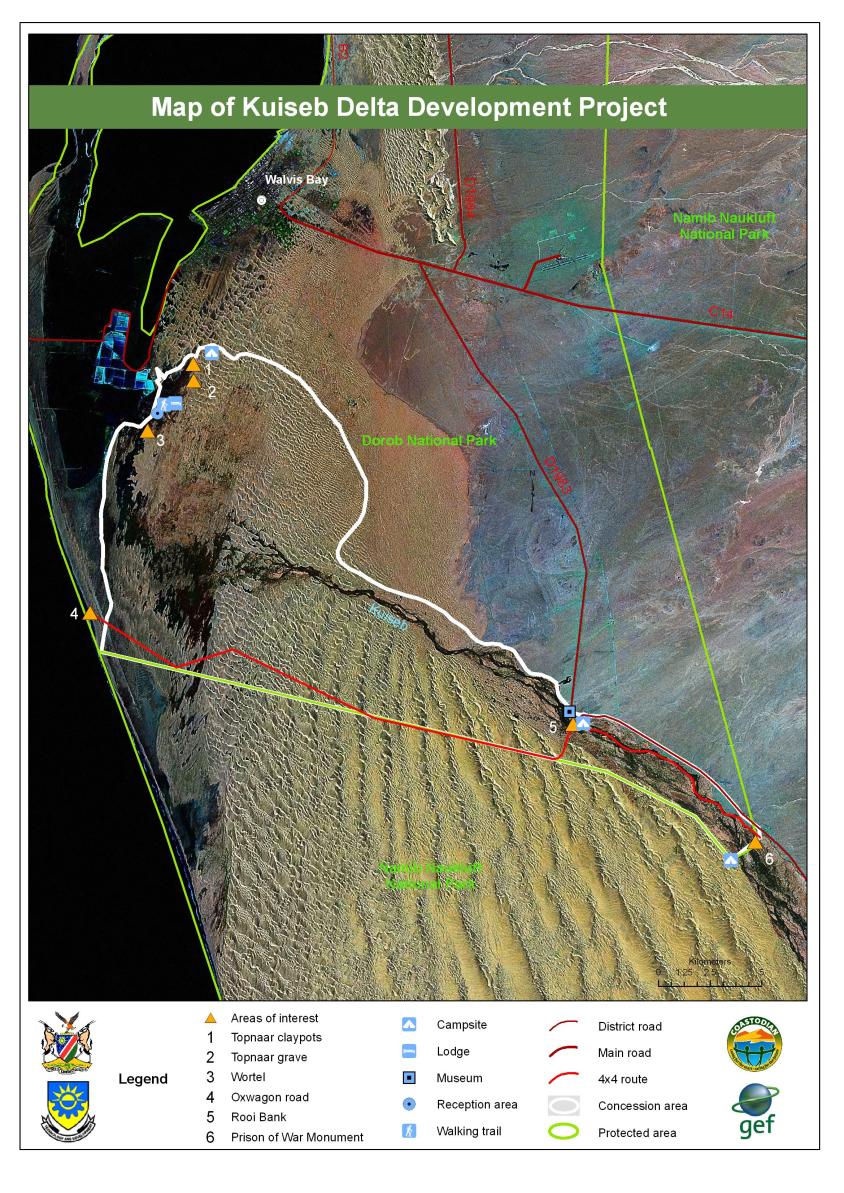

4.1.1 Kuiseb Delta Development Project/ Trust (KDDP/T)

Kuiseb Delta is located in Erongo region which is considered the hub of tourism in

Namibia. KDDP is located in an ideal tourism location - the meeting place of extreme

landscapes. On the one side is the Namib Desert, the oldest desert in the world while on

the other side is a massive lagoon and harbour flowing from the Atlantic Ocean. Both of

these landscapes lend themselves towards some of the most unique site seeing

opportunities in Namibia. The lagoon and harbour is home to a variety of species and a

large number of sea mammals and bird life. The Namib Desert on the other side is called

"The Living Desert", because of the large number of living species found there. Activities

include various different water related actions, like shore angling, boat angling, shark

angling, sightseeing and photographic boat cruises, sea kayaking and wind- and kite

surfing. Walvis Bay houses yearly one of the international legs of speed kite and wind

surfing. The proposed project provides additional activities in the coastal area. Envisaged

facilities and attendant activities will complement existing offerings. The additional

activities will boost current efforts to lengthen the average stay of tourists in the coastal

area (Nyakunu and Ndlovu, 2010).

The Topnaars community living in the Kuiseb Delta, submitted an application for a

Matching Grant to NACOMA with the main aim of establishing Community-Based

Tourism (CBT), called the Kuiseb Delta Development Project (KDDP). Upon approval of

the Matching Grant the KDDP submitted an application for a concession along the Kuiseb

Delta to MET. Conditions for concession applications required a feasibility report and

business plan. Subsequently, The Kuiseb Delta Development Trust (KDDT) was

registered on April 12, 2010 through a Trust Deed, in terms of the Trust Monies

Protection Act. The trust is a legal entity that can venture into formal commercial

agreements with business partners. It is an initiative being spearheaded by seven (7)

Trustees from the Topnaar community with the consent of the Topnaar Traditional

Authority. The trust comprises of 600 registered members. Clear guidelines on benefits

distribution, mandates and responsibilities have been drafted and a Steering Committee

comprising the Trustees is functioning. The concession which KDDT has applied for

spans the area east from Walvis Bay Meersig residential area, starting from the border of

Walvis Bay and state lands till Mile 7 reservoir including old Walvis Bay entry route near

the MWARD nursery (refer to Figure 4.1 below).

Figure 4.1: Kuiseb Delta Development Trust Concession Area (Nyakunu and Ndlovu, 2010)

The Kuiseb Delta Development Project (KDDP) seeks to offer more specialized tourism

services such as cultural tourism, educational/historical tourism and adventure tourism

through the provision of walking trails, scenic drives, dune drives, sand boarding, and

other activities relevant to its locality (Nyakunu and Ndlovu, 2010).

The feasibility study confirms that the project is significant and reasons for justification are as follow (Nyakunu and Ndlovu, 2010):

KDDP is a significant initiative since:

The Topnaar community will bring forth a rich cultural component to the trails. The

existing traditional customs and cultural harvesting of the !Nara presents another mile

stone in the promotion of cultural tourism. The historical and educational component

of the trail provides the overall experience.

The successful launch of the project will be another feature in the cap of CBNRM in

Namibia. It will be an additional opportunity to showcase Namibia‟s international

success in the promotion of CBRNMs.

Focus is on and around ecosystems of biodiversity importance i.e. bio-diversity being

conserved includes !Nara melons, Dune lark, Lichen fields, Dune habitats and gravel

plain habitats, Landscape aesthetics, Restriction of ORV traffic, etc.

It is aligned with community / local and national priorities such as empowering rural

communities through the provision of consumptive and non-consumptive rights over

natural resources, raising standard of living, creating employment opportunities,

alleviating poverty, etc.

The project will also include cottage industries and conservation issues.

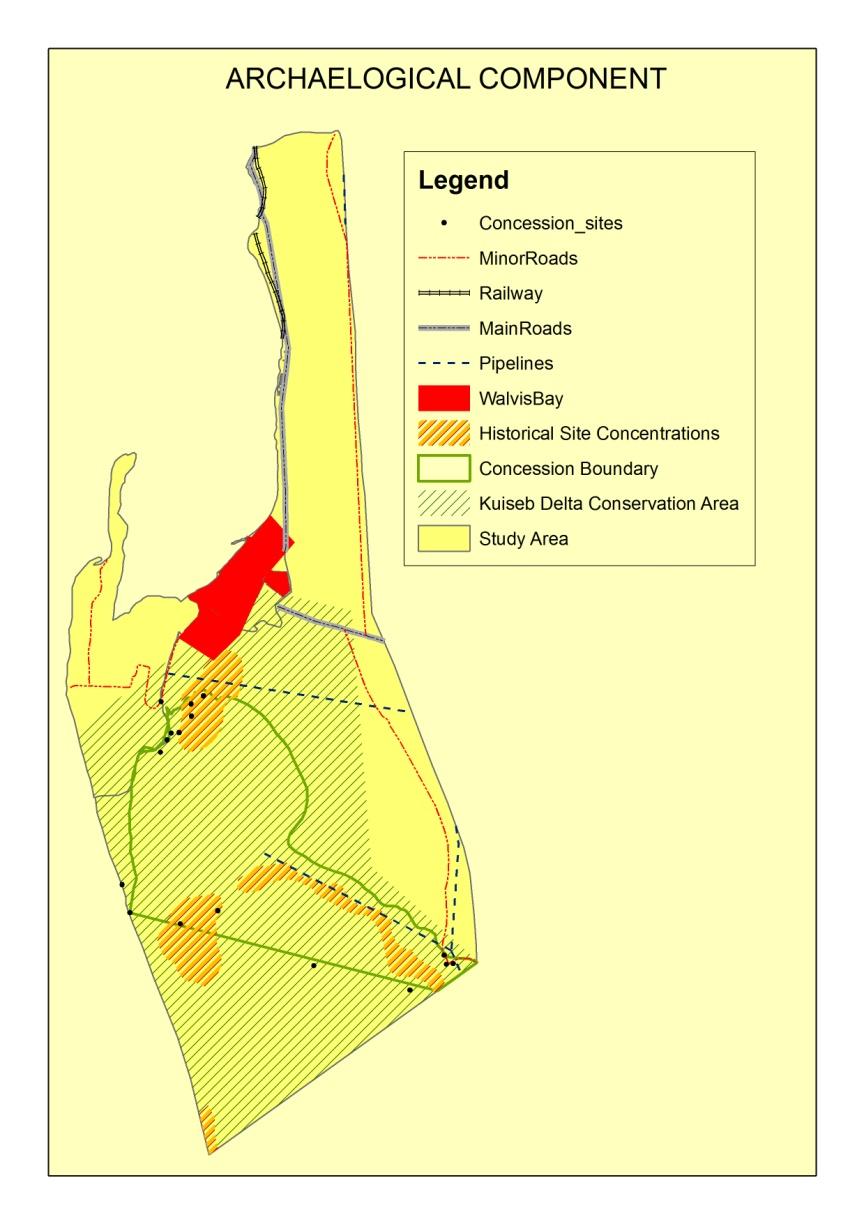

The Kuiseb Delta is unparalleled in Southern Africa for its archaeology which provides

a continuum of 2000 years, including detailed evidence from the last 250 years. By

1990s, 235 sites had been identified with 75% being from pre-contact times and 25%

showing evidence of contact ranging in age from 15th to 20th century. Though well

preserved the sites are vulnerable to natural and human influences. For instance, the

removal of items is reducing the archaeological / historical value of the sites which is

important to the nation and paramount to the Topnaar people.

KDDT can sell the project and generate funding for both capital and running costs. The

KDDP can be easily operated at a marginal cash surplus but would rely heavily on

collections from membership fees, labour subsidies for construction and maintenance,

donations and subsidized supplies for construction and maintenance. According to the

KDDT business plan, it is assumed that revenues will be generated solely from activities

such as trails, camping and guiding fees. These income streams will cover sufficiently the

capital, construction and operating funding needs of the project (Nyakunu and Ndlovu,

4.1.2 Walvis Bay Bird Paradise

The application for a Matching Grant to establish a bird watch paradise in Walvis Bay was

also submitted to NACOMA PCO. Subsequently, the feasibility and business plan was

compiled to guide the construction and operation of the project. Setting up a bird

watching camp was welcomed by everybody spoken to, no matter whether they were

birders, people involved in tourism & NGO's or officials in government or public

institutions. It was actually often queried why a country with a very high ranking in its bird

variety has to date not seen an operation of this kind set up.

The Walvis Bay Bird Paradise is situated 1300m from the circle of the intersection of the

Swakop – Walvis Bay road (B2) and the road to the Walvis Bay Airport / into the Namib

(C14). The Walvis Bay sewerage ponds where the paradise camp is erected is about

200m form the road. The pond is the most north-east of the reticulation pans of the

reticulation plant. It is visible from the road; it can be accessed by a short graveled up

ramp from the main road. Separated by 2 dunes to the south-east is the water carrying

pan with a range of birds, both sweet water and sea water birds.

BASELINE ENVIRONMENT

5.1 General Overview

This section presents the description of the natural environment that may be affected by

activities proposed in the study area (Cunningham, 2011).

5.2 Climatic Setting

This section presents the climatic system of the Erongo Region where the study area is

situated. In essence, Erongo region is characterised by aridity. The following various are

described in detail;

5.2.1 Temperature

Maximum and the minimum temperatures in the Namibia Desert near the coast are

moderated by the effects of the cold Benguela current and the regular fog bank (Reptile

Uranium Namibia, 2010). According to Christian (2006), the hottest month is February,

when maximum air temperatures can reach 40˚C but the average maximum 25˚C – 30˚C.

The coldest month is August, when the average minimum temperature is between 8˚C

and 12˚C depending on the distance from the coast (Ibid).

5.2.2 Precipitation

The study area falls within a rainfall range averaging 15 mm at coast and 35 mm further

inland (Christian, 2006). The rainfall can be described as extremely variable, patchy and

unreliable along coastal areas (Mendelsohn et.al, 2009). The coastal area receives fog

and extends about 20 Km inland (Mendelsohn et. al, 2009). The fog is sufficient to

support at biodiversity in the project area.

5.2.3 Wind

Near the coast strong winds prevail, but westerly to south westerly winds are also

frequent. As the distance from the coast towards inland increases, the wind speed

generally decreases and its direction become more variable (Christian, 2006).

5.3 Vertebrate fauna expected in the Kuiseb Delta and Dune belt

area

5.3.1 Introduction

A desktop study (i.e. literature review) was conducted between 20 and 24 May 2011 on

the vertebrate fauna (e.g. reptiles, amphibians, mammals and birds) expected to occur in

the general area defined as the Kuiseb River delta and dune belt area between Walvis

Bay and Swakopmund.

This literature review was to determine the actual as well as potential vertebrate fauna

associated with the general area commonly referred to as the Southern Namib or

Southern Desert (Giess 1971, Mendelsohn et al. 2002, Van der Merwe 1983). This area

is bordered inland by the Central Namib or Central Desert (Giess 1971, Mendelsohn et al.

2002). Climatically the coastal area is referred to as Cool Desert with a high occurrence

of fog (van der Merwe 1983). The Namib Desert Biome makes up a large proportion

(32%) of the land area of Namibia with parks in this biome making up 69% of the

protected area network or 29.7% of the biome (Barnard 1998). Four of 14 desert

vegetation types are adequately protected with up to 94% representation in the protected

area network in Namibia (Barnard 1998). With the exception of municipal land, the area

falls within the recently proclaimed Dorob National Park. No communal and freehold

conservancies are located in the general area with the closest communal conservancy

being the ≠Gaingu Conservancy in the Spitzkoppe area approximately 100 km to the

northeast (Mendelsohn et al. 2002, NACSO 2010).

Two important coastal wetlands – i.e. Walvis Bay Wetlands and Sandwich Harbour – both

Ramsar sites, occur in the area. According to Curtis and Barnard (1998) the entire coast

and the Walvis Bay lagoon as a coastal wetland, are viewed as sites with special

ecological importance in Namibia. The known distinctive values along the coastline are

its biotic richness (arachnids, birds and lichens) with the Walvis Bay lagoon‟s importance

being its biotic richness and migrant shorebirds as well as being the most important

Ramsar site in Namibia. The Ramsar site covers 12 600 ha with regular counts of birds

varying between 37 000 and well over 100 000 individuals, albeit mainly migratory

species (Kolberg n.d.). The Walvis Bay wetland is considered the most important coastal

wetland in southern Africa and one of the top 3 in Africa (Shaw et al. 2004). The

Sandwich Harbour Ramsar site covers 16 500 ha and falls within the Namib-Naukluft

Park and enjoys full protection (Kolberg n.d.). This area is a centre of concentration of

migratory shorebirds, waders and flamingos regularly supporting over 142 000 and 50

000 birds during summer and winter, respectively (Kolberg n.d.).

The area is bordered by the Kuiseb River to the south (Walvis Bay area) and the Swakop

River to the north (Swakopmund area) with catchment areas of 15 500 km² and 30 100

km², respectively (Jacobson et al. 1995).

The central coastal region and the Walvis Bay area in particular, is regarded as "relatively

low" in overall (all terrestrial species) diversity (Mendelsohn et al. 2002). Overall

terrestrial endemism in the area on the other hand is "moderate to high" (Mendelsohn et

al. 2002).

The overall diversity and abundance of large herbivorous mammals (big game) is viewed

as "low to medium" with 1-2 species while overall diversity of large carnivorous mammals

(large predators) is determined at 4 species with brown hyena being the most important

with "medium" densities expected in the area (Mendelsohn et al. 2002).

It is estimated that at least 54 reptile, 7 amphibian, 42 mammal and 182 bird species

(breeding residents) are known to or expected to occur in the general/immediate Walvis

Bay/Swakopmund area of which a high proportion are endemics.

5.3.2 Methods

Literature review

A comprehensive and intensive literature review (i.e. desktop study) regarding the

reptiles, amphibians, mammals and birds that could potentially occur in the

general/immediate Kuiseb delta and dune belt area was conducted using as many

references as manageable. A list of the references consulted can be viewed in the

Reference section.

5.3.3 Results

5.3.3.1 Reptile Diversity

Table 1 indicates the reptile diversity known and/or expected to occur in the general

Kuiseb delta and dune belt area between Walvis Bay and Swakopmund:

Table 5.1. Reptile diversity known and/or expected to occur in the general Kuiseb delta and

dune belt area – i.e. Walvis Bay and Swakopmund areas.

Species: Scientific name

Species: Common name

Namibian

and legal

TURTLES AND TERRAPINS

Pelomedusa subrufa

Marsh/Helmeted Terrapin

Thread Snakes

Leptotyphlops occidentalis

Western Thread Snake

SARDB Peripheral

Leptotyphlops labialis

Damara Thread Snake

Burrowing Snakes

Xenocalamus bicolour bicolor

Bicoloured Quill-snouted

Typical Snakes

Lamprophis fuliginosus

Brown House Snake

Lycophidion capense

Pseudaspis cana

Dipsina multimaculata

Dwarf Beaked Snake

Psammophis trigrammus

Western Sand Snake

Psammophis notostictus

Karoo Sand Snake

Psammophis leightoni

Namib Sand Snake

namibensis Dasypeltis scabra

Common/Rhombic Egg

Aspidelaps lubricus

infuscatus Aspidelaps scutatus scutatus

Shield-nose Snake

Naya nigricincta

Black-necked Spitting Cobra

Bitis arietans

Bitis caudalis

Bitis peringueyi

Péringuey‟s Adder

Typhlosaurus braini

Brains‟s Blind Legless Skink

Typhlacontias brevipes

FitzSimmons‟ Burrowing

Trachylepis occidentalis

Western Three-striped Skink

Trachylepis striata wahlbergi

Trachylepis sulcata

Western Rock Skink

Trachylepis variegata

Variegated Skink

variegate

Old World Lizards

Heliobolus lugubris

Meroles anchietae

Shovel-snouted Lizard

Meroles cuneirostris

Wedge-snouted Desert

Meroles micropholidotus

Small-scaled Desert Lizard

Meroles reticulates

Reticulated Desert Lizard

Meroles suborbitalis

Spotted Desert Lizard

Pedioplanis breviceps

Short-headed Sand Lizard

Pedioplanis namaquensis

Namaqua Sand Lizard

Pedioplanis inornata

Plain Sand Lizard

Plated Lizards

Cordylosaurus subtessellatus

Dwarf Plated Lizard

Monitors

Varanus albigularis

CITES Appendix II

Safe to Vulnerable

Agama planiceps

Namibian Rock Agama

Chameleons

Bradypodion pumilum

Cape Dwarf Chameleon

Introduced alien

CITES Appendix II

Chamaeleo namaquensis

Namaqua Chameleon

CITES Appendix II

Afroedura africana africana

African Flat Gecko

Chondrodactylus angulifer

Giant Ground Gecko

namibensis Narudasia festiva

Pachydactylus bicolour

Velvety Thick-toed Gecko

Pachydactylus kockii

Koch‟s Thick-toed Gecko

Pachydactylus turneri

Turner‟s Thick-toed Gecko

Pachydactylus scherzi

Schertz‟s Thick-toed Gecko

Pachydactylus rugosus

Rough Thick-toed Gecko

Pachydactylus weberi werneri Weber‟s Thick-toed Gecko

Palmatogecko rangei

Wed-footed Gecko

Ptenopus carpi

Carp‟s Barking Gecko

Ptenopus garrulus maculatus

Common Barking Gecko

Ptenopus kocki

Kock‟s Barking Gecko

Rhoptropus afer

Common Namib Day Gecko

Rhoptropus boultoni

Boulton‟s Namib Day Gecko

Rhoptropus bradfieldi

Bradfield‟s Namib Day

Namibian conservation and legal status according to the Namibian Conservation

Ordinance of 1975 – Griffin (2003)

Source for literature review: Alexander and Marais (2007), Branch (1998), Branch

(2008), Boycott and Bourquin 2000, Broadley (1983), Buys and Buys (1983),

Cunningham (2006), Griffin (1998a), Griffin (2003), Hebbard (n.d.), Marais (1992), Tolley

and Burger (2007)

Approximately 261 species of reptiles are known or expected to occur in Namibia thus

supporting approximately 30% of the continents species diversity (Griffin 1998a). At least

22% or 55 species of Namibian lizards are classified as endemic. The occurrence of

reptiles of "conservation concern" includes about 67% of Namibian reptiles (Griffin

1998a). Emergency grazing and large scale mineral extraction in critical habitats are

some of the biggest problems facing reptiles in Namibia (Griffin 1998a). The overall

reptile diversity and endemism in the Walvis Bay/Swakopmund area is estimated at

between 31-50 species and 17-24 species, respectively (Mendelsohn et al. 2002). Griffin

(1998a) presents figures of between 1-20 and 9-10 for endemic lizards and snakes,

respectively, from the general central coastal part of Namibia.

According to the literature review at least 54 species of reptiles are expected to occur in

the general Walvis Bay/Swakopmund area with 27 species being endemic – i.e. 50%

endemic, 1 species (Varanus albigularis) as vulnerable, 2 species as rare and

insufficiently known while 4 species have some form of international conservation status.

These consist of at least 17 snakes (2 thread snakes, 1 burrowing snake, 14 typical

snakes) of which 6 species (35%) are endemic, 1 terrapin, 16 lizards (50% endemic), 1

monitor, 1 agama, 2 chameleons (although the Cape Dwarf Chameleon is endemic to

South Africa it was introduced to gardens in the Walvis Bay area and thus does not occur

there naturally – i.e. alien) and 16 geckos (81% endemic).

Lizards (16 species with 8 species being endemic) and Gecko‟s (16 species with 13

species being endemic) are the most important group of reptiles expected from the

Walvis Bay/Swakopmund area. Namibia with approximately 129 species of lizards

(Lacertilia) has one of the continents richest lizard fauna (Griffin 1998a). Geckos

expected and/or known to occur in the Walvis Bay/Swakopmund area have the highest

occurrence of endemics (81%) of all the reptiles in this area. Griffin (1998a) confirms the

importance of the gecko fauna in Namibia. Both thread snakes expected from the area

are classified as endemic.

Due to the fact that reptiles are an understudied group of animals, especially in Namibia,

it is expected that more species may be located in the general Walvis Bay/Swakopmund

area than presented above.

5.3.3.2 Amphibian Diversity

Table 2 indicates the amphibian diversity known and/or expected to occur in the general

Kuiseb delta and dune belt area between Walvis Bay and Swakopmund:

Table 5.2. Amphibian diversity known and/or expected to occur in the general Kuiseb delta

and dune belt area – i.e. Walvis Bay and Swakopmund areas.

Species: Scientific name

Species: Common name

Poyntonophrynus dombensis

Poyntonophrynus hoeschi

Amietophrynus poweri

Power‟s Toad or Western Olive Toad

Rain Frogs

Breviceps adspersus

Common/Bushveld Rain Frog

Rubber Frog

Phrynomantis annectens

Marbled Rubber Frog

Bull and Sand Frogs

Tomopterna tandyi

Tandy‟s Sand Frog

Platannas

Xenopus laevis

Source for literature review: Carruthers (2001), Channing (2001), Channing and Griffin

(1993), Du Preez and Carruthers (2009), Passmore and Carruthers (1995)

Amphibians are declining throughout the world due to various factors of which much has

been ascribed to habitat destruction. Basic species lists for various habitats are not

always available with Namibia being no exception in this regard while the basic ecology of

most species is also unknown. Approximately 4 000 species of amphibians are known

worldwide with just over 200 species known from southern Africa and at least 57 species

expected to occur in Namibia. Griffin (1998b) puts this figure at 50 recorded species and

a final species richness of approximately 65 species, 6 of which are endemic to Namibia.

This "low" number of amphibians from Namibia is not only as a result of the generally

marginal desert habitat, but also due to Namibia being under studied and under collected.

Most amphibians require water to breed and are therefore associated with the permanent

water bodies, mainly in northeast Namibia.

The dry sandy coastal desert (Namib) and saline coastal areas are poor habitat for

amphibians. Although the ephemeral Kuiseb and Swakop Rivers reach the sea in the

Walvis Bay and Swakopmund areas, it seldom flows with temporary freshwater pools

being rare close to the coast. Other water bodies in the area are saline of nature and not

suitable habitat for amphibians. Gardens in Walvis Bay, Lang Strand and Swakopmund

can be suitable habitat and amphibians are known to occur here usually after having

being transported from elsewhere (Pers obs.). Overall, the saline coastal habitats are

marginal for amphibians. According to Mendelsohn et al. (2002), the overall frog diversity

in the Walvis Bay/Swakopmund area is estimated at between 1-3 species. Griffin (1998b)

puts the species richness in the general area between 1-2 species.

According to the literature review, up to 7 species of amphibians can occur in suitable

habitat in the general Walvis Bay/Swakopmund area. The area is under represented,

with 3 toads and 1 species each for rain, rubber and sand frog and platanna known

and/or expected (i.e. potentially could be found in the area) to occur in the area. Three

species (43%) namely Poyntonophrynus dombensis, Poyntonophrynus hoeschi and

Phrynomantis annectens are classified as endemic to Namibia (Griffin 1998b) while all 7

species are classified as "least concern" by the IUCN (IUCN 2010).

The Kuiseb and Swakop Rivers flooded for lengthy periods during the unusually high

2011 rainy season. This could have resulted in amphibians being transported into the

area which otherwise remains generally poor habitat.

5.3.3.3 Mammal Diversity

Table 3 indicates the mammal diversity known and/or expected to occur in the general

Kuiseb delta and dune belt area between Walvis Bay and Swakopmund:

Table 5.3. Mammal diversity known and/or expected to occur in the general Kuiseb delta

and dune belt area – i.e. Walvis Bay and Swakopmund areas.

Species: Scientific name

Species: Common name

Namibian

and legal

status

Eremitalpa granti

Grant‟s Golden Mole

Elephant Shrews

Macroscelides

Round-eared Elephant-

proboscideus

flavicaudatus

Bats

Lissonycteris angolensis

*Angolan Soft-furred Fruit

Tadarida aegyptiaca

Egyptian Free-tailed Bat

Cistugo seabrai

Namibian Wing-gland Bat

2Near Threatened

Laephotis namibensis

Namib Long-eared Bat

Nycteris thebaica

Common Slit-faced Bat

Rhinolophus clivosus

Geoffroy‟s Horseshoe Bat

1Near Threatened

Rhinilophus darling

Darling‟s Horseshoe Bat

1Near Threatened

Rhinolophus capensis

*Cape Horseshoe Bat

1Near Threatened;

2Near Threatened

Taphozous mauritianus

*Mauritanian Tomb Bat

Chaerephon ansorgei

*Ansorge‟s Free-tailed Bat

Sauromys petrophilus

Roberts‟s Flat-headed Bat

Miniopterus natalensis

Natal Long-fingered Bat

1Near Threatened

Eptesicus hottentotus

Long-tailed Serotine

Neoromicia zuluensis

Pipistrellus rueppellii

*Rüppel ‟s Pipistrel e

Hares and Rabbits

Lepus capensis

Rats and Mice

Parotomys littledalei

Littledale‟s Whistling Rat

1Near Threatened

namibensis

Rhabdomys pumilio

Mus musculus

Aethomys chrysophilus

Micaelamys (Aethomys)

Namaqua Rock Mouse

namaquensis Rattus rattus

Rattus norvegicus

Desmodillus auricularis

Short-tailed Gerbil

Gerbillurus paeba infernus

Hairy-footed Gerbil

Gerbillurus tytonis

Dune Hairy-footed Gerbil

Gerbillurus setzeri

Setzer‟s Hairy-footed Gerbil

or Namib Brush-tailed Gerbil

Petromyscus collinus

Pygmy Rock Mouse

Mastomys coucha

Southern Multimammate

Petromys typicus

1Near Threatened

Carnivores

Hyaena brunnea

1Near Threatened

2Near Threatened

Crocuta crocuta

1Near Threatened

Felis silvestris

African Wild Cat

CITES Appendix II

Vulpes chama

Canis mesomelas

Black-backed Jackal

Ictonyx striatus

Suricata suricatta

marjoriae

Antelopes

Sylvicapra grimmia

Antidorcas marsupialis

Oryx gazelle

1SARDB (2004); 2IUCN (2010)

* Unconfirmed bat species although potentially could occur in area according to habitat

modelling (Monadjem et al. 2010)

Source for literature review: De Graaff (1981), Griffin (2005), Estes (1995), Joubert and

Mostert (1975), Monadjem et al. (2010), Skinner and Smithers (1990), Skinner and

Chimimba (2005) and Taylor (2000)

Namibia is well endowed with mammal diversity with at least 250 species occurring in the

country. These include the well known big and hairy as well as a legion of smaller and

lesser-known species. Currently 14 mammal species are considered endemic to Namibia

of which 11 species are rodents and small carnivores of which very little is known. Most

endemic mammals are associated with the Namib and escarpment with 60% of these

rock-dwelling (Griffin 1998c). According to Griffin (1998c) the endemic mammal fauna is

best characterized by the endemic rodent family Petromuridae (Dassie rat) and the rodent

genera Gerbillurus and Petromyscus. The overall mammal diversity in the Walvis Bay

area is estimated at between 16-30 species with 3-4 species being endemic to the area

(Mendelsohn et al. 2002).

Overall terrestrial diversity – all species – is classified as "low" in the western coastal

parts of Namibia (Mendelsohn et al. 2002). The overall diversity (1-2 species) and

abundance of large herbivorous mammals is low in the Walvis Bay area with Springbok

and Oryx having the highest density of the larger species (Mendelsohn et al. 2002). The

overall abundance and diversity of large carnivorous mammals is relatively high (4

species) in the Walvis Bay area with Brown Hyena having the highest density of the

larger species (Mendelsohn et al. 2002).

According to the literature review, up to 42 species of mammals are known and/or

expected to occur in the general Walvis Bay/Swakopmund area of which 11 species

(29.1%) are classified as endemic. According to the Namibian legislation 1 species is

classified as rare, 3 species as vulnerable, 4 species as insufficiently known, 3 species as

invasive aliens, 2 species as huntable game, 1 species as problem animal while 2

species (both bats) are not listed. Eleven species are listed with various international

conservation statuses of which 2 species are classified as vulnerable (Eremitalpa granti

and Cistugo seabrai) and 8 species as near threatened by the SARDB (SARDB 2004).

The IUCN (IUCN 2010) classifies 3 species as near threatened (Cistugo seabrai,

Rhinolophus capensis and Hyaena brunnea) while 1 species is classified as a CITES

Appendix II species.

The House Mouse (Mus musculus) and the rats Rattus rattus and Rattus norvegicus are

viewed as invasive aliens to the area. Mus musculus are generally known as casual

pests and not viewed as problematic although they are known carriers of "plague" and

can cause economic losses. The biggest problem with the Rattus species is economic

losses and garden pests along the coast (Griffin 2003). Mammal species probably

underrepresented in the above mentioned table for the general area are the bats as this

group has not been well documented from the arid western parts of Namibia.

At least 40.5% and 35.7% of the mammalian fauna that occur or are expected to occur in

the Walvis Bay/Swakopmund area are represented by rodents (17 species) and bats (15

species) of which 9 species (21.4%) are endemic to Namibia. Some species such as

Petromys typicus are not expected to occur in the dune belt area as they typically favour

rocky habitat and are known to occur behind the dune belt in such habitat. Habitats often

not valued as unique are the dune hummocks and seemingly barren gravel plains along

the coast. Habitat alteration and overutilization are the two primary processes

threatening most mammals (Griffin 1998c).

5.3.3.4 Avian Diversity

Table 4 indicates the bird diversity known and/or expected to occur in the general Kuiseb

delta and dune belt area between Walvis Bay and Swakopmund:

Table 5.4. Bird diversity known and/or expected to occur in the general Kuiseb delta and

dune belt area – i.e. Walvis Bay and Swakopmund areas. This table excludes migratory

birds (e.g. Petrel, Albatross, Skua, etc.) and species breeding extralimital (e.g. stints,

sandpipers, etc.) and rather focuses on birds that are breeding residents or can be found

in the area during any time of the year. This would imply that many more birds (e.g.

Palaearctic migrants) could occur in the area depending on "favourable" environmental

Table 5.4. Bird diversity known and/or expected to occur in the general Kuiseb delta and

dune belt area – i.e. Walvis Bay and Swakopmund areas.

Species: Scientific name

Species: Common name

Status: Southern

Struthio camelus

Podiceps cristatus

Great Crested Grebe

Tachybaptus ruficollis

Podiceps nigricollis

Black-necked Grebe

Pelecanus onocrotalus

Great White Pelican

Pelecanus rufescens

Pink-backed Pelican

Phalacrocorax lucidus

Morus capensis

Breeding endemic

Phalacrocorax capensis

Near-threatened;

Breeding endemic

Phalacrocorax neglectus

Phalacrocorax africanus

Phalacrocorax coronatus

Crowned Cormorant

Anhinga melanogaster

Ardea cinerea

Ardea melanocephala

Black-headed Heron

Ardea purpurea

Egretta garzetta

Egretta intermedia

Yellow-billed Egret

Egretta alba

Egretta ardesiaca

Bubulcus ibis

Ardeola ralloides

Ixobrychus minutes

Scopus umbretta

Ciconia nigra

Phoenicopterus ruber

Greater Flamingo

Phoenicopterus minor

Dendrocygna viduata

Alopochen aegyptiacus

Anas capensis

Anas hottentota

Anas erythrorhyncha

Anas smithii

Netta erythrophthalma

Southern Pochard

Sagittarius serpentarius

Gyps africanus

White-backed Vulture

Aegypius tracheliotus

Lappet-faced Vulture

Circaetus pectoralis

Black-chested Snake-

Elanus caeruleus

Black-shouldered Kite

Aquila verreauxii

Verreaux‟s Eagle

Aquila rapax

Polemaetus bellicosus

Buteo augur

Melierax canorus

Southern Pale Chanting

Falco peregrines

Peregrine Falcon

Falco biarmicus

Falco chicquera

Red-necked Falcon

Falco rupicolus

Falco rupicoloides

Francolinus adspersus

Red-billed Francolin

Trunix sylvatica

Kurrichane Buttonquail

Porphyrio porphyrio

African Purple Swamphen

Gallinula chloropus

Fulica cristata

Red-knobbed Coot

Ardeotis kori

Neotis ludwigii

Ludwig‟s Bustard

Eupodotis rueppellii

Rüppell‟s Korhaan

Eupodotis afra

Actophilornis africanus

Rostratula benghalensis

Haematopus moquini

Near threatened;

Charadrius marginatus

White-fronted Plover

Charadrius pallidus

Chestnut-banded Plover

Charadrius pecuarius

Kittlitz‟s Plover

Charadrius tricollaris

Three-banded Plover

Vanellus armatus

Blacksmith Lapwing

Recurvirostra avosetta

Himantopus himantopus

Black-winged Stilt

Burhinus capensis

Spotted Thick-knee

Cursorius rufus

Burchel ‟s Courser

Rhinoptilus africanus

Double-banded Courser

Larus dominicanus

Larus cirrocephalus

Grey-headed Gull

Larus hartlaubii

Hartlaub‟s Gull

Sterna bergii

Sterna balaenarum

Near threatened;

Breeding endemic

Chlidonias hybridus

Pterocles namaqua

Namaqua Sandgrouse

Pterocles bicinctus

Columba guinea

Columba livea

Streptopelia capicola

Cape Turtle Dove

Streptopelia senegalensis

Streptopelia capicola

Cape Turtle-Dove

Oena capensis

Agapornis roseicollis

Rosy-faced Lovebird

Corythaixoides concolor

Grey Go-away-bird

Tyto alba

Otus leucotis

Southern White-faced

Glaucidium perlatum

Pearl-spotted Owlet

Bubo africanus

Spotted Eagle Owl

Bubo lacteus

Caprimulgus tristigma

Freckled Nightjar

Apus bradfieldi

Bradfield‟s Swift

Colius colius

White-backed Mousebird

Urocolius indicus

Red-faced Mousebird

Ceryle rudis

Merops hirundineus

Swallow-tailed Bee-eater

Upupa epops

Phoeniculus cyanomelas

Tockus monteiri

Monteiro‟s Hornbil

Tockus nasutus

African Grey Hornbill

Lybius leucomelas

Dendropicos fuscescens

Cardinal Woodpecker

Mirafra sabota

Mirafra curvirostris

Long-billed Lark

Calendulauda

erythrochlamys Chersomanes albofasciata

Spike-heeled Lark

Calandrella cinerea

Alauda starki

Ammomanopsis grayi

Certhilauda subcoronata

Karoo Long-billed Lark

Eremopterix verticalis

Grey-backed Sparrowlark

Hirundo fuligula

Riparia paludicola

Brown-throated Martin

Dicrurus adsimilis

Fork-tailed Drongo

Corvus capensis

Corvus albus

Parus cinerascens

Anthoscopus minutes

Cape Penduline Tit

Turdoides bicolour

Pycnonotus nigricans

African Red-eyed Bulbul

Monticola brevipes

Short-toed Rock Thrush

Namibornis herero

Oenanthe monticola

Mountain Wheatear

Cercomela familiaris

Cercomela tractrac

Cercomela schlegelii

Myrmecocichla formicivora

Erythropygia paena

Parisoma subcaeruleum

Chestnut-vented Tit-

Parisoma layardi

Layard‟s Tit-Babbler

Zosterops pallidus

Orange River White-eye

Sylvietta rufescens

Long-biled Crombec

Eremomela icteropygialis

Yellow-bellied Eremomela

Eremomela gregalis

Acrocephalus baeticatus

African Reed-Warbler

Acrocephalus gracilirostris

Lesser Swamp-Warbler

Cisticola aridulus

Desert Cisticola

Cisticola subruficapilla

Grey-backed Cisticola

Cisticola juncidis

Zitting Cisticola

Prinia flavicans

Black-chested Prinia

Melaenornis mariquensis

Marico Flycatcher

Bradornis infuscatus

Muscicapa striata

Spotted Flycatcher

Batis pririt

Motacilla capensis

Anthus navaeseelandiae

Richard‟s Pipit

Anthus similes

Long-billed Pipit

Anthus vaalensis

Tchagra australis

Brown-crowned Tchagra

Lanius collaris

Laniarius atrococcineus

Crimson-breasted Shrike

Nilaus afer

Telophorus zeylonus

Creatophora cinerea

Wattled Starling

Lamprotornis nitens

Cape Glossy Starling

Onychognathus nabouroup

Pale-winged Starling

Chalcomitra senegalensis

Scarlet-chested Sunbird

Nectarinia mariquensis

Nectarinia fusca

Passer domesticus

Passer motitensis

Passer melanurus

Passer griseus

Southern Grey-headed

Sporopipes squamifrons

Scaly-feathered Finch

Plocepasser mahali

White-browed Sparrow-

Philetairus socius

Ploceus velatus

Southern Masked Weaver

Quelea quelea

Red-billed Quelea

Euplectes orix

Southern Red Bishop

Estrilda erythronotos

Black-faced Waxbill

Estrilda astrild

Amadina erythrocephala

Red-headed Finch

Vidua regia

Shaft-tailed Whydah

Serinus alario

Black-headed Canary