Cpccrn.org

The randomized comparative pediatric critical illness

stress-induced immune suppression (CRISIS) prevention trial

Joseph A. Carcillo, MD; J. Michael Dean, MD; Richard Holubkov, PhD; John Berger, MD; Kathleen L. Meert, MD;K. J. S. Anand, MBBS, DPhil; Jerry Zimmerman, MD, PhD; Christopher J. L. Newth, MB, ChB; Rick Harrison, MD;Jeri Burr, MS, RN-BC; C. C. R. C. Douglas F. Willson, MD; Carol Nicholson, MD

Objectives: Nosocomial infection/sepsis occurs in up to

Measurements and Main Results: There were no differences by

40% of children requiring long-term intensive care. Zinc, se-

assigned treatment in the overall population with respect to time

lenium, glutamine, metoclopramide (a prolactin secretalogue),

until the first episode of nosocomial infection/sepsis (median

and/or whey protein supplementation have been effective in

whey protein 13.2 days vs. zinc, selenium, glutamine, and intra-

reducing infection and sepsis in other populations. We evalu-

venous metoclopramide 12.1 days; p ⴝ .29 by log-rank test) or

ated whether daily nutriceutical supplementation with zinc,

the rate of nosocomial infection/sepsis (4.83/100 days whey pro-

selenium, glutamine, and metoclopramide, compared to whey

tein vs. 4.99/100 days zinc, selenium, glutamine, and intravenous

protein, would reduce the occurrence of nosocomial infection/

metoclopramide; p ⴝ .81). Only 9% of the 293 subjects were

sepsis in this at-risk population.

immunocompromised and there was a reduction in rate of noso-

Design: Randomized, double-blinded, comparative effective-

comial infection/sepsis with zinc, selenium, glutamine, and intra-

ness trial.

venous metoclopramide in this immunocompromised group (6.09/

Setting: Eight pediatric intensive care units in the NICHD Col-

100 days whey protein vs. 1.57/100 days zinc, selenium,

laborative Pediatric Critical Care Research Network.

glutamine, and intravenous metoclopramide; p ⴝ .011).

Patients: Two hundred ninety-three long-term intensive care pa-

Conclusion: Compared with whey protein supplementation,

tients (age 1–17 yrs) expected to require >72 hrs of invasive care.

zinc, selenium, glutamine, and intravenous metoclopramide con-

Interventions: Patients were stratified according to immuno-

ferred no advantage in the immune-competent population. Further

compromised status and center and then were randomly assigned

evaluation of zinc, selenium, glutamine, and intravenous meto-

to receive daily enteral zinc, selenium, glutamine, and intravenous

clopramide supplementation is warranted in the immunocompro-

metoclopramide (n ⴝ 149), or daily enteral whey protein (n ⴝ

mised long-term pediatric intensive care unit patient. (Pediatr Crit

144) and intravenous saline for up to 28 days of intensive care

Care Med 2012; 13:000 – 000)

unit stay. The primary end point was time to development of

KEY WORDS: glutamine; nosocomial infection; prolactin; sele-

nosocomial sepsis/infection. The analysis was intention to treat.

nium; sepsis; whey protein; zinc

Centers for Disease Control

care. Critical illness stress induces lym-

tional supplementation is needed in this

and Prevention recommen-

phopenia and lymphocyte dysfunction as-

population at risk for stress-induced lym-

dations and bundled inter-

sociated with hypoprolactinemia (1) and

phocyte dysfunction and nosocomial in-

ventions for preventing catheter-associ-

also deficiencies in zinc and selenium (2,

ated bloodstream infection, ventilator-

3) and amino acids (4, 5). Because lym-

Metoclopramide, a prolactin secreta-

associated pneumonia, and urinary

phocyte integrity is important for the im-

logue, administered at the dosage com-

catheter-associated infections, nosoco-

mune response to fight infection, stan-

monly used for gastrointestinal prokinesis

mial infection/sepsis remains a signifi-

dard nutritional practice in critically ill

maintains prolactin levels in the high-

cant cause of morbidity in critically ill

children includes zinc, selenium, and

normal range in children. In mechanicallyventilated adults, metoclopramide delayedtime to onset of nosocomial pneumoniaby 50% but had no effect on the rate of

From the Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC

of Health and Human Services (DHHS; U10HD050096,

(JAC), Pittsburgh, PA; University of Utah (JMD, RH, JB);

U10HD049981, U10HD500009, U10HD049945,

nosocomial pneumonia or mortality (6).

Children's National Medical Center (JB); Children's

U10HD049983, U10HD050012, and U01HD049934).

In malnourished children, zinc supple-

Hospital of Michigan (KLM); Arkansas Children's Hos-

Members of the Data Safety Monitoring Board

mentation reduced morbidity and mor-

pital (KJSA); Seattle Children's Hospital (JZ); Children's

include Jeffrey R. Fineman, MD, Jeffrey Blumer, PhD,

tality with severe pneumonia (7, 8) or

Hospital Los Angeles (CJLN); University of California at

MD, Thomas P. Green, MD, and David Glidden, PhD.

Los Angeles (RH), Los Angeles, CA; University of Vir-

For information regarding this article, E-mail:

diarrhea (9 –11) and reduced infectious

ginia Children's Hospital (CDFW); and National Institute

disease mortality in small-for-gestation-

of Child Health and Human Development (CN).

Copyright 2011 by the Society of Critical Care

al-age infants (12). Selenium supplemen-

Supported, in part, by the following cooperative

Medicine and the World Federation of Pediatric Inten-

tation (13) or glutamine-enriched enteral

agreements from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National

sive and Critical Care Societies

nutrition (14) also reduced the risk of

Institute of Child Health and Human Development

(NICHD), National Institutes of Health (NIH), Department

nosocomial sepsis in preterm neonates.

Pediatr Crit Care Med 2012 Vol. 13, No. 4

Enteral glutamine safely maintains T 1

lymphocyte function for bacterial killing(15, 16).

Essential amino acids are also impor-

tant to overall immune function and lym-phocyte function in particular (5). Wheyprotein provides all the essential aminoacids needed to maintain immune func-tion in immune cells. Experimental ani-mal studies show that whey protein sup-plementation facilitates maturation ofthe immune system and is protectiveagainst rotavirus (17–21). Randomizedhuman clinical studies of whey proteinhave demonstrated improved lymphocytefunction and reduction in coinfection inhuman immunodeficiency virus-infectedchildren, reduction in infection in se-verely burned children, and improved im-munologic response to immunization inthe elderly (22–26).

The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National

Institute of Child Health and Human De-velopment Collaborative Pediatric Criti-cal Care Research Network investigatorshypothesized that critical illness stress-induced immune suppression-relatednosocomial infection/sepsis would be

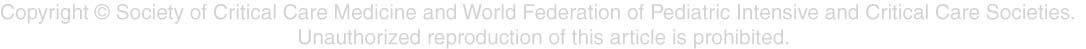

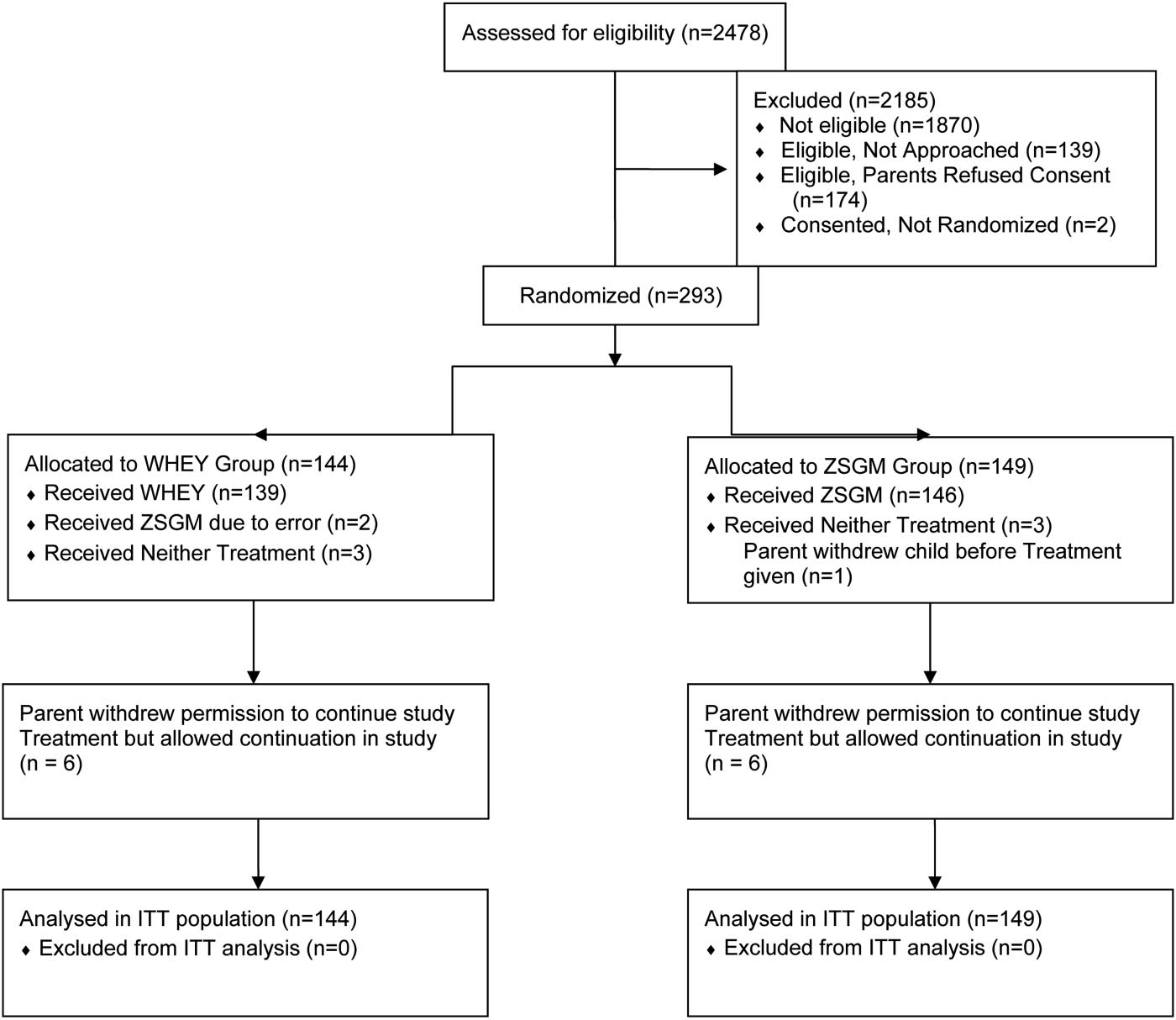

Figure 1. Screening, enrollment, randomization, and study completion.

more effectively prevented by prophylac-tic supplementation of "standard" nutri-

tor (J.M.D.) acted as the sponsor. The study was

Safety Monitoring Board before authorizing

tional practice with added zinc, selenium,

registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (number

enrollment of infants younger than 1 yr. After

glutamine, and metoclopramide, (ZSGM)

the first interim analysis, the Data Safety Mon-

than by prophylactic supplementation

Patients were eligible for enrollment if

itoring Board deferred this authorization until

with added amino acid (whey protein).

they: were older than 1 yr and younger than 18

a second interim analysis could be reviewed.

The Collaborative Pediatric Critical Care

yrs of age; were within the first 48 hrs of PICU

At the time of the second review, the trial was

Research Network designed a random-

admission; had an endotracheal tube, central

terminated for futility. Therefore, no infants

ized, double-blinded, comparative effec-

venous catheter (new or old, tunneled or not

younger than 1 yr were enrolled in the trial.

tiveness trial with the primary hypothesis

tunneled), or urinary catheter; were antici-

The study commenced in April 2007 and ter-

that daily ZSGM would prolong the time

pated to have an indwelling arterial or venous

minated in November 2009.

to development of nosocomial infection/

catheter for blood sampling during the first 3

After informed consent was obtained from

sepsis compared to daily whey protein. In

days of study enrollment; and were anticipated

parents, subjects were randomized by tele-

this article we report the results of the

to have venous access and an enteral feeding

phone according to an a priori design using

critical illness stress-induced immune

tube for the administration of study drugs.

randomized blocks of variable length, strati-

suppression prevention trial.

Patients were excluded from enrollment if

fied according to center and immunocompro-

they: had a known allergy to metoclopramide;

mised status. Immunocompromised status

MATERIALS AND METHODS

were expected to have planned removal of en-

was defined by the known presence of acquired

dotracheal tube, central venous, and urinary

immune deficiency syndrome, cancer, trans-

This randomized, double-blinded, compara-

catheters within 72 hrs after study enroll-

plantation, primary immune deficiency, or

tive study was performed on two parallel groups

ment; had suspected intestinal obstruction;

chronic immune suppressant therapy. Chil-

of children at eight pediatric intensive care units

had intestinal surgery or bowel disruption;

dren were randomized in a 1:1 ratio into the

(PICUs) in the Collaborative Pediatric Critical

had other contraindications to the enteral ad-

two arms of the trial in these stratified groups.

Care Research Network. The Institutional Re-

ministration of drugs or nutrients; received

All patients, medical and nursing staffs, clini-

view Boards of all Collaborative Pediatric Critical

chronic metoclopramide therapy before en-

cal site monitors, and most DCC staff re-

Care Research Network centers approved the

rollment; had a known allergy to whey (cow's

mained blinded throughout the study period.

protocol and informed consent documents. Pa-

milk) or soy-based products; had been dis-

The DCC biostatistician (R.H.) prepared Data

rental permission was provided for each subject.

charged from the PICU in the previous 28

Safety Monitoring Board reports and reviewed

An independent Data Safety Monitoring Board

days; had been previously enrolled in this

results in the two arms but remained blinded

was appointed by the NICHD, and two interim

study; or had a positive pregnancy test. Pa-

to actual group assignment throughout the

safety and efficacy analyses were planned. The

tients were also excluded if their parents indi-

study period. Central and clinical site research

study was performed under an Investigational

cated a lack of commitment to aggressive in-

pharmacists and the pharmacy site monitor

New Drug application from the Food and Drug

tensive care therapies.

were unblinded throughout the study.

Administration (investigational new drug

The Food and Drug Administration re-

Subjects were randomized to receive en-

74,500), for which the DCC Principal Investiga-

quired an interim analysis review by the Data

teral whey protein powder and intravenous

Pediatr Crit Care Med 2012 Vol. 13, No. 4

Table 1. Epidemiologic and clinical characteristics at admission

diatric Critical Care Research Network inves-tigators adjudicated the presence or absence of

Zinc, Selenium, Glutamine,

a nosocomial clinical sepsis or infection event

and Metoclopramide Group

for every subject. Each case was reviewed in-

Group (N ⫽ 144)

dependently by two investigators and pre-sented in detail so that consensus for all out-

Age (yrs), median (range)

comes was attained. All participants in this

Pediatric logistic organ dysfunction, median (range)

adjudication process were blinded to treat-

Pediatric risk of mortality, median (range)

ment arm through the study period.

Organ failure index, median (range)

Secondary outcome variables of this study

Immunocompromised (%)

included the rate of nosocomial infection/sepsis

Postoperative pediatric intensive care unit

per 100 PICU days, number of antibiotic-free

Primary diagnosis (%)

days, incidence of prolonged lymphopenia

(ALC ⱕ1000/mm3 for ⱖ7 days), serum prolac-

tin, zinc, and selenium levels before treatment

and after 7 days of treatment, and the safety

Cardiovascular disease

indicator 28-day mortality and adverse events.

Serum zinc and selenium levels were classified

as deficient if they were below the pediatric

reference ranges of the core laboratory. Zinc

deficiency was defined as a level ⬍0.60 g/mL

Human immunodeficiency virus

in children aged 10 yrs or younger and

g/mL in children aged at least 11 yrs. Sele-

nium deficiency was defined as a level ⬍70

ng/mL in children aged 10 yrs or younger and

⬍95 ng/mL in children aged at least 11 yrs.

Chronic diagnoses (%)

Prolactin deficiency was defined as a level of

Malnutrition (reported as primary or secondary

⬍3 ng/mL across all ages. Glutamine levels

Infection status at entry (%)

were not measured because they are not con-

Existing infection

sidered indicative of total body reserves.

The sample size was calculated to provide

No infection or sepsis

90% power to detect an inverse hazard rate of

Existing lymphopenia (ALC ⱕ1000/mm3)

Baseline core laboratory data (%)

1.5 using a two-sided nonparametric test (log-

rank test) with type I error (␣) of 0.05. This

Prolactin deficiency

required accrual of subjects until 263 had nos-

Selenium deficiency

ocomial events; the estimated total samplesize was 600 subjects based on initial eventrate estimates. A log-rank test with a two-sided

saline (whey protein group) or ZSGM (ZSGM

between admission to the PICU and occur-

␣ ⫽ 0.05, stratified by immune-compromised

group). Subjects assigned to the whey protein

rence of nosocomial infection/clinical sepsis in

status, was used to compare the primary end

group received 0.3 g/kg beneprotein each

PICU patients who have endotracheal tubes,

point of freedom from nosocomial infection or

morning and intravenous saline every 12 hrs.

central venous catheters, or urinary catheters.

sepsis (from time of admission to the PICU

Subjects assigned to the ZSGM group received

Nosocomial events were defined as occurring

until up to 5 days after discharge from the

zinc (20 mg), selenium (40 g age 1–3 yrs,

at least 48 hrs after PICU admission during the

PICU) between treatment arms. Outcome

100 g age 3–5 yrs, 200 g age 5–12 yrs, 400

hospital stay until 5 days after discharge from

rates over time are presented using Kaplan-

g adolescent), and glutamine (0.3 g/kg) each

the PICU; for children remaining in the PICU

Meier freedom from event curves. In the sub-

morning, and intravenous metoclopramide

for ⬎28 days after randomization, events were

group of immunocompromised whey protein

(0.2 mg/kg, maximum 10 mg) every 12 hrs. All

counted until day 33. The study protocol re-

patients, median time to nosocomial infec-

study drugs were shipped from a central phar-

quired that patients be randomized within 48

tion/sepsis was derived at the 50.5% event-free

macy (University of Utah) and dispensed by

hrs of PICU admission and that study drug

site research pharmacists. Subjects received

administration begin within 72 hrs of PICU

study drug until discharge from the PICU or

admission. According to Center for Disease

In prespecified analyses complementary to

for 28 days from the time of randomization,

Control and Prevention definitions, clinical

the primary analysis, rates of infection were

whichever occurred earlier. Enteral drugs

sepsis occurs when patients older than 1 yr

analyzed using Poisson regression analyses,

were administered by feeding tube and discon-

have development of fever (ⱖ38°C), hypoten-

which count multiple events for a single sub-

tinued if the feeding tube was removed or if

sion (ⱕ90 mm Hg), or oliguria (ⱕ20 mL/hr)

ject. Additionally, numbers and proportions of

contraindications to enteral feeding developed

and a clinician initiates antibiotic therapy with

antibiotic-free days during the PICU stay were

during the study. Intravenous drugs were dis-

no positive microbiological evidence and no

compared between study arms using the Wil-

continued if the intravenous was removed.

other recognized cause. Nosocomial infection

coxon rank-sum test. Incidence of prolonged

The hypothesis of the critical illness stress-

occurs when microbiologically (culture, anti-

lymphopenia and all-cause mortality and ad-

induced immune suppression Prevention trial

gen, polymerase chain reaction, or antibody)

verse events at 28 days after randomization

was that daily prophylaxis with enteral zinc,

proven infection is observed in a patient with

were analyzed using the chi-square test or

selenium, and glutamine, and intravenous

fever, hypothermia, chills, or hypotension.

exact analogues when numbers of events were

metoclopramide would delay the time (hours)

The treatment arm blinded Collaborative Pe-

small. Four ZSGM-assigned subjects (one of

Pediatr Crit Care Med 2012 Vol. 13, No. 4

Figure 2. Top, Freedom from nosocomial sepsis according to assigned treatment for all randomized patients. Numbers above the horizontal time axis

denote number of patients remaining at risk at each time point. p ⫽ .29 for log-rank test comparing curves between study arms, stratified by immune

competent status. Middle, Freedom from nosocomial infection/sepsis according to assigned treatment for patients immunocompromised at study entry.

Numbers above the horizontal time axis denote number of patients remaining at risk at each time point. p ⫽ .24 for log-rank test comparing curves between

study arms. Lower, Freedom from nosocomial infection/sepsis according to assigned treatment for patients who were immune-competent at study entry.

Numbers above the horizontal time axis denote number of patients remaining at risk at each time point. p ⫽ .16 for log-rank test comparing curves between

study arms.

whom received no study treatment) had un-

ment, randomization, and study comple-

Treatment with ZSGM did not delay

known 28-day survival status.

tion results.

the time until nosocomial infection/

Five factors (immunocompromised status,

Table 1 shows the epidemiologic and

sepsis compared to treatment with whey

postoperative status, gender, race/ethnicity,

clinical characteristics of the study pop-

protein (median time, whey protein 13.2

and center) were prespecified for subgroup

ulation at the time of enrollment in both

days vs. ZSGM 12.1 days; log-rank p ⫽

analysis, and the Data Safety Monitoring

treatment arms. The median age of chil-

.29; Fig. 2 top). The median PICU stay

Board subsequently added another factor (in-

dren was 7 yrs and ⬍10% were immuno-

was 10 days. Of subjects at risk for an

fection or sepsis at study entry). The inten-

compromised on entry. Baseline charac-

event, approximately 50% in each treat-

tion-to-treat approach was used for all study

teristics were equally distributed between

ment arm were event-free at 14 days after

analyses of efficacy. Analysis by treatment re-

the study arms. Among patients assigned

PICU admission. The effect of immuno-

ceived was performed for the safety outcomes

to whey protein, 46.5% received paren-

compromised status on time to nosoco-

of mortality and occurrence of adverse events.

teral nutrition and 89.6% received en-

mial infection/sepsis was not significant

teral nutrition, compared to 43.0% and

(median time in immunocompromised

90.6% of patients assigned to ZSGM. The

patients, whey protein 10 days vs. ZSGM

We enrolled 293 subjects (Fig. 1). En-

proportion of patients who were allowed

32.4 days; median time in immune com-

rollment was terminated for futility after

nothing by mouth during one or more

petent patients, whey protein 13.2 days

the second interim analysis indicated that

PICU study days was 55% in the whey

vs. ZSGM 11.8 days; p ⫽ .12) for interac-

the conditional power to determine a

protein arm and 53% in the ZSGM arm,

tion between treatment group and immu-

beneficial effect by ZSGM, compared to

with the average proportion of PICU

nocompromised status in the time-to-

the whey protein therapy, was ⬍10%.

study days being allowed nothing by

event analysis (Fig. 2 middle, bottom).

Figure 1 shows the screening, enroll-

mouth at 14% and 13%, respectively.

Other subgroup factors examined were

Pediatr Crit Care Med 2012 Vol. 13, No. 4

Figure 2. Continued.

Pediatr Crit Care Med 2012 Vol. 13, No. 4

Table 2. Rates of nosocomial infection/sepsis, days of invasive lines, urinary catheterization, and

lenium (40% vs. 38%), glutamine (8% vs.

mechanical ventilation by treatment group

7%) primarily as part of routine TPN, andmetoclopramide (3% vs. 5%) for facilita-

Zinc, Selenium, Glutamine,

tion of nasoduodenal tube placement or

and Metoclopramide

gastroesophageal reflux, respectively.

Group (N ⫽ 144)

Group (N ⫽ 149)

Seven-day levels of all three measures

Total events (infection or sepsis)

were significantly higher in ZSGM pa-

Total pediatric intensive care unit days

tients than whey protein patients, and

Total study daysa

change from baseline was also higher

Mean events/patient/100 study days

(p ⬍ .001 for all six comparisons). At 7

95% confidence interval

days, zinc deficiency was present in 19 of

Therapeutic risk factorsDays in pediatric intensive care unit

83 (23%) ZSGM subjects vs. 36 of 80

(45%) whey protein subjects, selenium

Ventilator days (mean/median)

deficiency in 10 of 84 (12%) ZSGM sub-

Central venous catheter days (mean/median)

jects vs. 23 of 80 (29%) whey protein

Endotracheal tube days (mean/median)

subjects, and prolactin deficiency in 3 of

Urinary catheter days (mean/median)

Total ventilator days

84 (4%) ZSGM subjects vs. 14 of 81 (17%)

Total respiratory infections

whey protein subjects. Controlling for

Mean respiratory infections/patient

presence of baseline deficiencies, ZSGM

Per 100 ventilator days (95% confidence interval)

subjects with 7-day measures showed sig-

Total urinary catheter days

Total urinary tract infections

nificantly lower 7-day deficiency rates

Mean urinary tract infections/patient

compared to whey protein subjects for

Per 100 urinary catheter days (95%

zinc (p ⫽ .001 by Cochran-Mantel-

confidence interval)

Haenszel test), selenium (p ⫽ .009), and

Total central venous catheter days

prolactin (p ⫽ .014).

Total bacteremia infections

Mean bacteremia infections/patient

Overall 28-day mortality was 8.1%

Per 100 central venous catheter days (95%

among the 284 children who received

confidence interval)

whey protein or ZSGM and had known28-day status. There was no significant

aStudy days indicates days in pediatric intensive care unit plus additional days after pediatric

difference in 28-day mortality by treat-

intensive care unit discharge that patient was followed-up for events (5 days unless patient was

ment received between whey protein and

discharged from hospital earlier).

ZSGM (8/139 [5.8%] vs. 15/145 [10.3%];p ⫽ .16). Among the 287 children receiv-

not significantly associated with the pri-

treatment arms (Table 2). Distribution of

ing treatment, there were 2624 adverse

mary end point.

events, sites of infection, and infecting

events, including 113 serious adverse

There was no difference in the rate of

organisms were also generally similar be-

events with no significant differences by

nosocomial infection or clinical sepsis

tween the treatment groups (Table 3).

treatment received for whey protein and

per 100 PICU days between the ZSGM and

In the immunocompromised popula-

ZSGM. Among 139 subjects receiving

whey protein groups (Table 2; p ⫽ .81).

tion, the rate of nosocomial infection/

only whey protein treatment, adverse

Examining study days in the PICU, me-

sepsis was reduced in the ZSGM group

events were reported in 126 (90.6%) and

dian number of antibiotic-free days (2 vs.

compared with the whey protein group

serious adverse events were reported in

1; p ⫽ .09) and proportion of days (17%

(unadjusted p ⫽ .006 for interaction be-

37 (26.6%), whereas among 148 subjects

vs. 10%; p ⫽ .19) did not differ between

tween treatment group and immunocom-

receiving ZSGM regimen adverse events

subjects assigned to whey protein vs.

promised status; Table 4). The causes for

were reported in 135 (91.2%) and serious

ZSGM. There was no significant differ-

immune compromise in whey protein

adverse events were reported in 39

ence in the incidence of prolonged lym-

compared to the ZSGM groups were bone

(26.4%). There were also no differences

phopenia (ALC ⱕ1000/mm3 for ⱖ7 days)

marrow transplant two vs. three, other

in specific adverse events, including diar-

between subjects assigned to whey pro-

organ transplant five vs. one, cancer one

rhea (whey protein 12.2% vs. ZSGM

tein (12/144 [8.3%] vs. ZSGM 5/149

vs. three, human immunodeficiency virus

12.2%), dysrhythmias (arrhythmia, extra-

[3.4%]; p ⫽ .07). In the study population,

zero vs. one, severe neutropenia one vs.

systole, nodal rhythm; whey protein 4.3%

41% receiving whey protein and 42% re-

one, chronic high-dose steroids/immune

vs. ZSGM 4.1%), and abnormal move-

ceiving ZSGM had development of noso-

suppressants one vs. three, congenital

ment (akathisia, choreoathetosis, dyski-

comial infection or sepsis. Approximately

immunodeficiency one vs. one, and ther-

nesia, dystonia; whey protein 2.9% vs.

one-third of patients had development of

apeutic hypothermia zero vs. one.

nosocomial infection and one-fifth had

Among subjects with available base-

development of sepsis. Days of invasive

line values, zinc deficiency was present at

lines, urinary catheterization, and me-

baseline in 235 of 280 (84%), selenium

chanical ventilation and rates of site-

deficiency in 156 of 278 (56%), and pro-

Similar to previous literature, we ob-

specific infections based on denominators

lactin deficiency in 68 of 284 (24%) (Ta-

served that nosocomial infection/sepsis

of ventilator days, urinary catheter days,

ble 1). Among whey protein and ZSGM

occurred in ⬎40% of long-term PICU pa-

and central venous catheter days were

subjects, standard of care included the

tients, with ⬍50% of these children be-

not significantly different between the

common use of zinc (44% vs. 39%), se-

ing free from nosocomial infection or

Pediatr Crit Care Med 2012 Vol. 13, No. 4

Table 3. Nosocomial infection/sepsis and sites of nosocomial infection by treatment group

needed, perhaps in a specialized PICUnetwork with a larger immunocompro-

Zinc, Selenium, Glutamine,

mised population, or in a PICU network

and Metoclopramide

with a larger number of centers to prop-

Group (N ⫽ 144)

Group (N ⫽ 149)

erly assess the significance of this signal.

Patients with events

With regard to limitations, several

One or more events (%)

study design and performance variables

Nosocomial infection (%)

require the reader's consideration. First,

Nosocomial sepsis (%)

this trial was performed in the "standard

Site of infection

practice" setting. Protein, zinc, and sele-

Lower respiratory

nium are an accepted part of "standard"

Upper respiratory

pediatric enteral and parenteral nutrition

in the intensive care setting (29, 30) and

Skin or soft tissue

no effort was made to control this nutri-

tional practice. The study results cannotbe applied to patients who are without

any nutrition in the PICU. Second, ourtrial compared the effectiveness of two

Total infecting organisms

nutriceutical strategies to one another,

Candida albicans

rather than to placebo. The research

planning committee wanted to follow

previous study designs of glutamine sup-

Candida glabrata

Candida lusitanae

plementation in newborns that used sin-

gle amino acids as "placebos" to address

Gram-negative bacilli

potential criticism that an apparent effect

in a glutamine arm could be an effect of

protein nutrition rather than of glu-

tamine per se. This rationale is problem-

atic because all amino acids have specific

immune cell effects and therefore are not

Gram-positive bacilli

true placebos (5). Whey protein was the

Gram-negative cocci

only Food and Drug Administration-

approved amino acid supplement avail-

Gram-positive cocci

able to us. Because whey protein is mar-

Staphylococcus coagulase negative

keted as immune nutrition, we designed

a comparative effectiveness trial rather

than a true placebo-controlled trial. A

true placebo arm without any zinc, sele-

nium, or protein was considered outside

of human subjects standards. Two ongoingadult trials comparing the use of a dopa-

sepsis at 14 days and median time to

The ZSGM supplement did not prevent

mine-2 antagonist to placebo in mechani-

nosocomial infection or sepsis being just

persistent lymphopenia or nosocomial in-

cal ventilation and zinc, selenium, and glu-

less than 14 days (27). Similar to previous

fection/sepsis compared with essential

tamine supplements to placebo in severe

reports, we also found a high incidence of

amino acid supplementation from whey

sepsis (NCT0013978, NCT00300391) will

critical illness stress-related zinc and se-

protein in the overall study population.

give information on the effect of these

lenium deficiency, as well as prolactin

We stratified the randomization of pa-

supplements in the absence of concomi-

deficiency in 24% and lymphopenia in

tients to nutriceutical treatment arms ac-

tant protein supplementation. Approxi-

nearly 40% of the patients (1, 28). The

cording to immunocompromised status

mately ten patients in each treatment

observation that nearly 95% of subjects

because we thought it was biologically

arm either did not receive the assigned

had deficiencies at enrollment supports

plausible that the T 2 phenotype-domi-

treatment, or they had their treatments

the study design that used the multi-

nant immunocompromised group of pa-

stopped prematurely on parental request.

modal ZSGM supplement strategy and

tients would benefit differentially from

Post hoc analysis excluding these patients

analyzed the effects on both the pre hoc

ZSGM supplementation. In this regard,

did not change the overall findings of the

stratified immune competent and immu-

we did observe a reduction in the noso-

study. Fourth, a low number of antibiot-

nocompromised populations. We ob-

comial infection/sepsis rate with use of

ic-free days in the subjects enrolled in

served more frequent resolution of zinc,

ZSGM in this at-risk population. Because

either arm of this study was discovered.

selenium, and prolactin deficiencies at 7

⬍10% of our general PICU population This calls into question whether high an-

days with ZSGM, but this pharmacoki-

was immunocompromised, the small

tibiotic use diminished any effects of the

netic effect was not matched with the

sample size leads us to view these find-

nutriceuticals. However, post hoc analy-

hypothesized pharmacodynamic effect.

ings rather cautiously. Repeated study is

sis found no association between extent

Pediatr Crit Care Med 2012 Vol. 13, No. 4

Table 4. Rates of nosocomial infection/sepsis per 100 days by treatment group and immunocompro-

immune system during zinc deficiency.

Annu Rev Nutr 2004; 24:277–298

3. Stone CA, Kawai K, Kupka R, et al: Role of

Zinc, Selenium, Glutamine,

selenium in HIV infection. Nutr Rev 2010;

and Metoclopramide

4. Roth E: Immune and cell modulation by

amino acids. Clin Nutr 2007; 26:535–544

5. Li P, Yin YL, Li D, et al: Amino acids and

Total events (infection or sepsis)

immune function. Br J Nutr 2007; 98:

Total pediatric intensive care unit days

6. Yavagal DR, Karnad DR, Oak JL: Metoclopra-

Mean events/patient/100 study days

6.09 (3.33–10.32)

1.57 (0.53–3.73)

mide for preventing pneumonia in critically

(95% confidence interval)

ill patients receiving enteral tube feeding: Arandomized controlled trial. Crit Care Med

Zinc, Selenium, Glutamine,

2000; 28:1408 –1411

and Metoclopramide

7. Brooks WA, Yunus M, Santosham M, et al:

Group (N ⫽ 133)

group (N ⫽ 135)

Zinc for severe pneumonia in very young

children: Double-blind placebo-controlled

Total events (infection or sepsis)

trial. Lancet 2004; 363:1683–1688

Total pediatric intensive care unit days

8. Fischer Walker C, Black RE: Zinc and the

risk for infectious disease. Annu Rev Nutr

Mean events/patient/100 study days

4.72 (3.87–5.69)

5.44 (4.47–6.55)

2004; 24:255–275

(95% confidence interval)

9. Baqui AH, Black RE, El Arifeen S, et al: Zinc

therapy for diarrhoea increased the use oforal rehydration therapy and reduced the useof antibiotics in Bangladeshi children.

of antibiotic use and evidence of treat-

(Data Coordinating Center), Salt Lake

J Health Popul Nutr 2004; 22:440 – 442

ment effect.

City, UT: J. Michael Dean, MD, MBA, Jeri

10. Bhatnagar S, Bahl R, Sharma PK, et al: Zinc

Burr, MS, RN-BC, CCRC, Amy Donald-

with oral rehydration therapy reduces stool

son, MS, Richard Holubkov, PhD, Angie

output and duration of diarrhea in hospital-

Webster, MStat, Stephanie Bisping, RN,

ized children: A randomized controlled trial.

Nosocomial infection and sepsis re-

Teresa Liu, MPH, Brandon Jorgenson,

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2004; 38:34 – 40

mains a prevalent public health problem

BS, Rene Enriquez, BS, Jeff Yearley, BS;

11. Raqib R, Roy SK, Rahman MJ, et al: Effect of

in critically ill children with long-term

Children's National Medical Center, WA

zinc supplementation on immune and in-

stay in the PICU. Implementation of Cen-

DC: John Berger, MD, Angela Wratney,

flammatory responses in pediatric patients

ters for Disease Control and Prevention-

MD, Jean Reardon, BSN, RN; Children's

with shigellosis. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 79:

recommended practices is the first step in

Hospital of Michigan, Detroit, MI: Kath-

prevention. Our study was performed on

leen L. Meert, MD, Sabrina Heidemann,

12. Sazawal S, Black RE, Menon VP, et al: Zinc

the premise that evaluation of the com-

supplementation in infants born small for

MD, Maureen Frey, PhD, RN; Arkansas

parative effectiveness of prophylactic nu-

gestational age reduces mortality: A prospec-

Children's Hospital, Little Rock, AR: KJS

tritional support strategies could inform

tive, randomized, controlled trial. Pediatrics

Anand, MBBS, DPhil, Parthak Prodhan,

further improvement. The novel multi-

2001; 108:1280 –1286

MD, Glenda Hefley, MNSc, RN; Seattle

13. Darlow BA, Austin NC: Selenium supplemen-

modal strategy designed and used to re-

Children's Hospital, Seattle, WA: Jerry

tation to prevent short-term morbidity in

duce critical illness stress-induced zinc,

Zimmerman, MD, PhD, David Jardine,

preterm neonates. Cochrane Database Syst

selenium, glutamine, and prolactin defi-

MD, Ruth Barker, RRT; Children's Hospi-

Rev 2003; 4:CD003312

ciencies was successful in part in revers-

tal Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA: Chris-

14. van den Berg A, van Elburg RM, Westerbeek

ing these deficiencies. It conferred no ad-

topher J. L. Newth, MB, ChB, J. Francisco

EA, et al: Glutamine-enriched enteral nutri-

vantage in nosocomial infection and

Fajardo, CLS (ASCP), RN, MD; Mattel

tion in very-low-birth-weight infants and ef-

sepsis prevention in immune-competent

Children's Hospital at University of Cali-

fects on feeding tolerance and infectious

children compared to whey-based amino

fornia Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA: Rick

morbidity: A randomized controlled trial.

acid supplementation. Further study of

Harrison, MD; University of Virginia Chil-

Am J Clin Nutr 2005; 81:1397–1404

the ability of ZSGM supplementation to

15. Boelens PG, Houdijk AP, Fonk JC, et al: Glu-

dren's Hospital, Charlottesville VA: Doug-

prevent nosocomial infection and sepsis

tamine-enriched enteral nutrition increases

las F. Willson, MD; National Institute of

in the immunocompromised PICU popu-

in vitro interferon-gamma production but

Child Health and Human Development,

lation is warranted.

does not influence the in vivo specific anti-

Bethesda, MD: Carol Nicholson, MD,

body response to KLH after severe trauma. A

Tammara Jenkins, MSN RN.

prospective, double blind, randomized clini-

cal study. Clin Nutr 2004; 23:391– 400

16. Yalcin SS, Yurdakok K, Tezcan I, et al. Effect

Members of the Collaborative Pediat-

of glutamine supplementation on diarrhea,

ric Critical Care Research Network par-

1. Felmet KA, Hall MW, Clark RS, et al: Pro-

interleukin-8 and secretory immunoglobulin

ticipating in this study: Children's Hospi-

longed lymphopenia, lymphoid depletion,

A in children with acute diarrhea. J Pediatr

tal of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA: Joseph

and hypoprolactinemia in children with nos-

Gastroenterol Nutr 2004; 38:494 –501

Carcillo, MD, Michael Bell, MD, Alan

ocomial sepsis and multiple organ failure.

17. Ha E, Zemel MB: Functional properties of

Abraham, BA, Annette Seelhorst, RN,

J Immunol 2005; 174:3765–3772

whey, whey components, and essential

Jennifer Jones RN; University of Utah

2. Fraker PJ, King LE: Reprogramming of the

amino acids: mechanisms underlying health

Pediatr Crit Care Med 2012 Vol. 13, No. 4

benefits for active people (review). J Nutr

effects of dietary whey proteins in mice.

26. Freeman SL, Fisher L, German JB, et al:

Biochem 2003; 14:251–258

J Dairy Res 1995; 62:359 –368

Dairy proteins and the response to pneu-

18. Low PP, Rutherfurd KJ, Gill HS, et al: Effect

22. Micke P, Beeh KM, Buhl R: Effects of long-

movax in senior citizens: A randomized, dou-

of dietary whey protein concentrate on pri-

term supplementation with whey proteins on

ble-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Ann

mary and secondary antibody responses in

plasma glutathione levels of HIV-infected pa-

N Y Acad Sci 2010; 1190:97–103

immunized BALB/c mice. Int Immunophar-

tients. Eur J Nutr 2002; 41:12–18

27. Leclerc F, Leteutre S, Duhamel A, et al: Cu-

macol 2003; 3:393– 401

23. Micke P, Beeh KM, Schlaak JF, et al: Oral

mulative influence of organ dysfunctions and

19. Perez-Cano FJ, Marin-Gallen S, Castell M, et

supplementation with whey proteins in-

septic state on mortality of critically ill chil-

al: Supplementing suckling rats with whey

creases plasma glutathione levels of HIV-

dren. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2005; 171:

protein concentrate modulates the immune

infected patients. Eur J Clin Invest 2001;

response and ameliorates rat rotavirus-

28. Skelton JA, Havens PL, Werlin JL: Nutrient

induced diarrhea. J Nutr 2008; 138:

24. Moreno YF, Sgarbieri VC, da Silva MN, et al:

deficiencies in tube fed children. Clin Pediatr

Features of whey protein concentrate supple-

2006; 45:37– 41

20. Perez-Cano FJ, Marin-Gallen S, Castell M, et

mentation in children with rapidly progressive

29. Jeejeebhoy K: Zinc essential trace element

al: Bovine whey protein concentrate supple-

HIV infection. J Trop Pediatr 2006; 52:34 –38

for parenteral nutrition. Gastroenterology

mentation modulates maturation of immune

25. Alexander JW, MacMillan BG, Stinnett JD, et

2009; 137(5 Suppl):S7–S12

system in suckling rats. Br J Nutr 2007;

al: Beneficial effects of aggressive protein

30. Shenkin A: Selenium in intravenous nutri-

98(Suppl 1):S80 –S84

feeding in severely burned children. Ann

tion. Gastroenterology 2009; 137(Suppl 5):

21. Wong CW, Watson DL: Immunomodulatory

Surg 1980; 192:505–517

Pediatr Crit Care Med 2012 Vol. 13, No. 4

Source: http://www.cpccrn.org/documents/PediatrCritCare2012Carcillo.pdf

Caregiver Lifeline Program Resources for Transplant Families This document is a good starting point for identifying potential transplant-related resources for patients, their caregivers and families. We've included a variety of information about transplant, transplant fundraising resources, grant assistance providers, travel assistance, prescription coverage, and living donor support.

Volume 2, Number 1, June 2009 ISSN 1995-6681 Pages 1 -6 Jordan Journal of Earth and Environmental Sciences Diurnal and Seasonal Variation of Air Pollution at Al-Hashimeya Sana'a Abed El-Raoof Odat * Department of Earth Science and Environment, Faculty of Natural Resources and Environment,Hashemite University, Jordan Abstract