Microsoft word - pubp 758 - final paper _p. walsh_

Table of Contents

Abstract . 2 Purpose . 2 Introduction and Background . 3 Methodology . 6 Results and Discussion . 9 Conclusion and Policy Implications . 18 Works Cited . 20 Appendix A . 23 Appendix B . 24 Appendix C . 25

Patrick J. Walsh - 1

Abstract:

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is the most common blood-borne infection in the United

States and is seven times more prevalent than HIV/AIDS infections in the United States

(CDC Division of HIV/AIDS website). Moreover, there are approximately 170 million

cases of HCV worldwide (Thomas et al. 450). Chronic HCV infection is the leading

cause of liver transplants because of liver cirrhosis is and is also one of the leading causes

of liver cancer (American Liver Society website). Even with all of these contributing

factors, HCV remains an afterthought in the minds of public health legislators from

nations all over the world. Despite these facts, HCV carries several public health policy

implications, such as the effects on international drug enforcement laws and the diversion

of resources away from other infectious disease programs.

Purpose:

This paper will examine the global burden of this disease by examining medical,

economic, and societal implications that care and treatment of this disease carry as well

as further developments and steps that are being taken to put viral hepatitis C on the

public health legislation radar. Some of the topics that will be discussed are the number

of global cases of HCV, its amplification of the progression of end-stage liver disease in

the human body, the cost of treatment for the disease, its associations with HIV/AIDS,

the stigma brought on by treatment for the disease, and the development of an effective

vaccine for HCV. After considering all of these empirical factors along with the politics

of hepatitis C, a policy decision can be made.

Patrick J. Walsh - 2

Introduction and Background:

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) was first referred to as "non-A, non-B hepatitis," and

was discovered during the late 1980s (Thomas et al. 450). It was uncovered when a team

of doctors was studying hepatitis A and B infections (HAV and HBV respectively) in

patients who had received blood transfusions. Their findings revealed that "…25% of

these cases of transfusion-associated hepatitis (TAH) were linked to hepatitis B but no

hepatitis A." (Marco 1). The remaining 75% of these cases were attributed to the non-A,

non-B hepatitis (NANBH). Because the patients experiencing NANBH infections

experienced either no or very mild symptoms, these doctors "…did not initially consider

NANBH to be a very serious disease." (Marco 1) After further research was conducted,

however, it was determined that NANBH resulted in serious chronic infection that, in

some cases, led to liver cirrhosis. In 1988, the virus was named:

The NANBH agent remained a virologic enigma.until researchers at the Chiron Corporation used an ambitious molecular approach on large volumes of high-titer infectious chimpanzee plasma from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). They extracted RNA, cloned it into an expression vector, and screened the expressed product with presumed immune sera. A single positive clone was found in the millions screened, and, within a year, the entire genome was sequenced and the agent was identified as a novel flavivirus the hepatitis C virus (HCV). (qtd. in Marco 1)1

HCV is a disease that affects the human liver. Its name is derived from the Greek words

for "liver" (hepato) and "inflammation" (-itis) (Hepatitis C Association website).2 Since

its naming, HCV has gone on to become the most common blood-borne infection in the

1 This is a portion of a report written by H.J. Alter entitled "Discovery of non-A, non-B hepatitis and identification of its etiology," published in 1999, that Marco references in his work. 2 The Hepatitis C Association is a community based organization operating out of Scotch Plains, New Jersey. They are dedicated to performing education and outreach on HCV across the United States in both clinical and patient populations. See <http://www.hepcassoc.org/Aboutus.html>

Patrick J. Walsh - 3

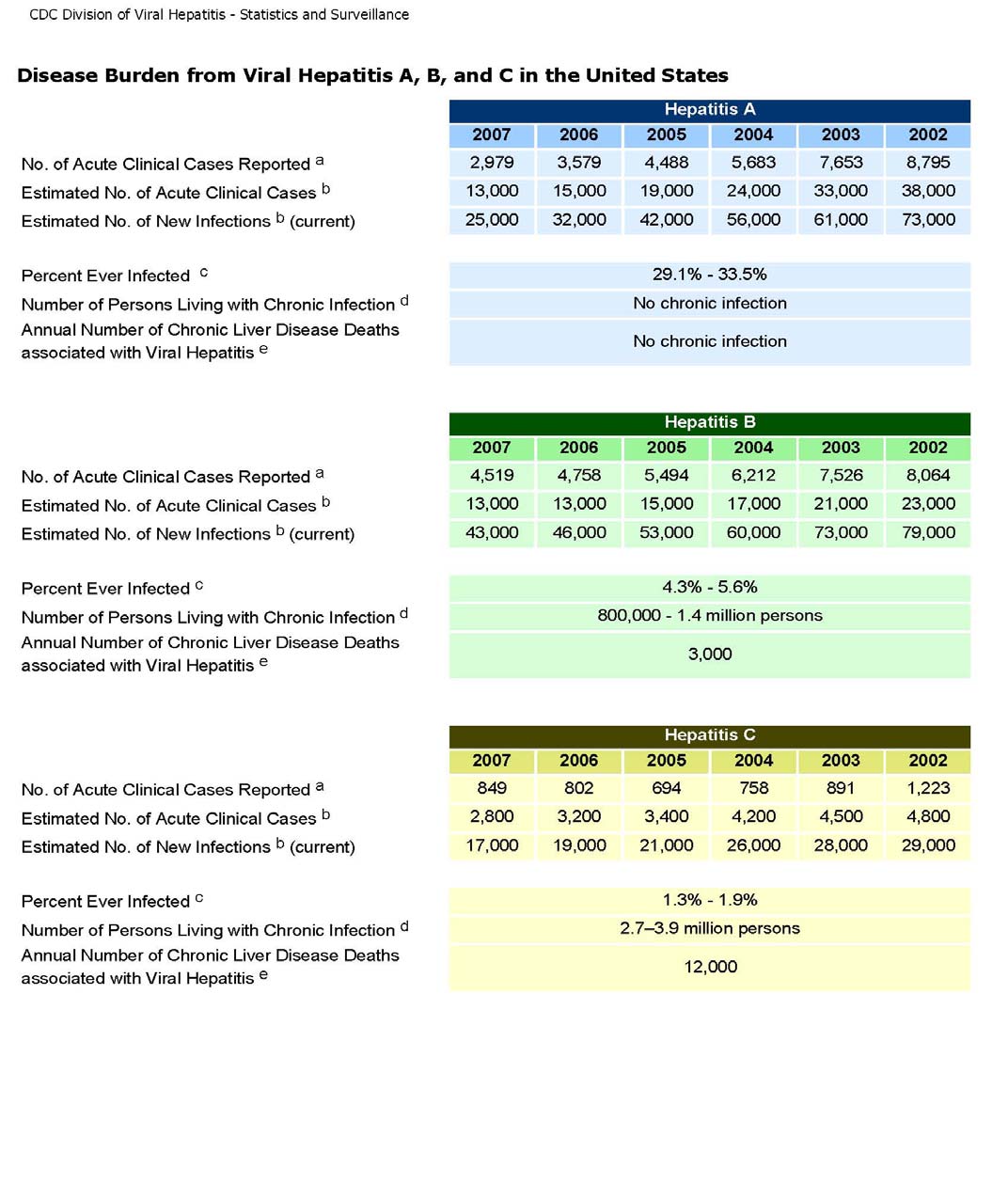

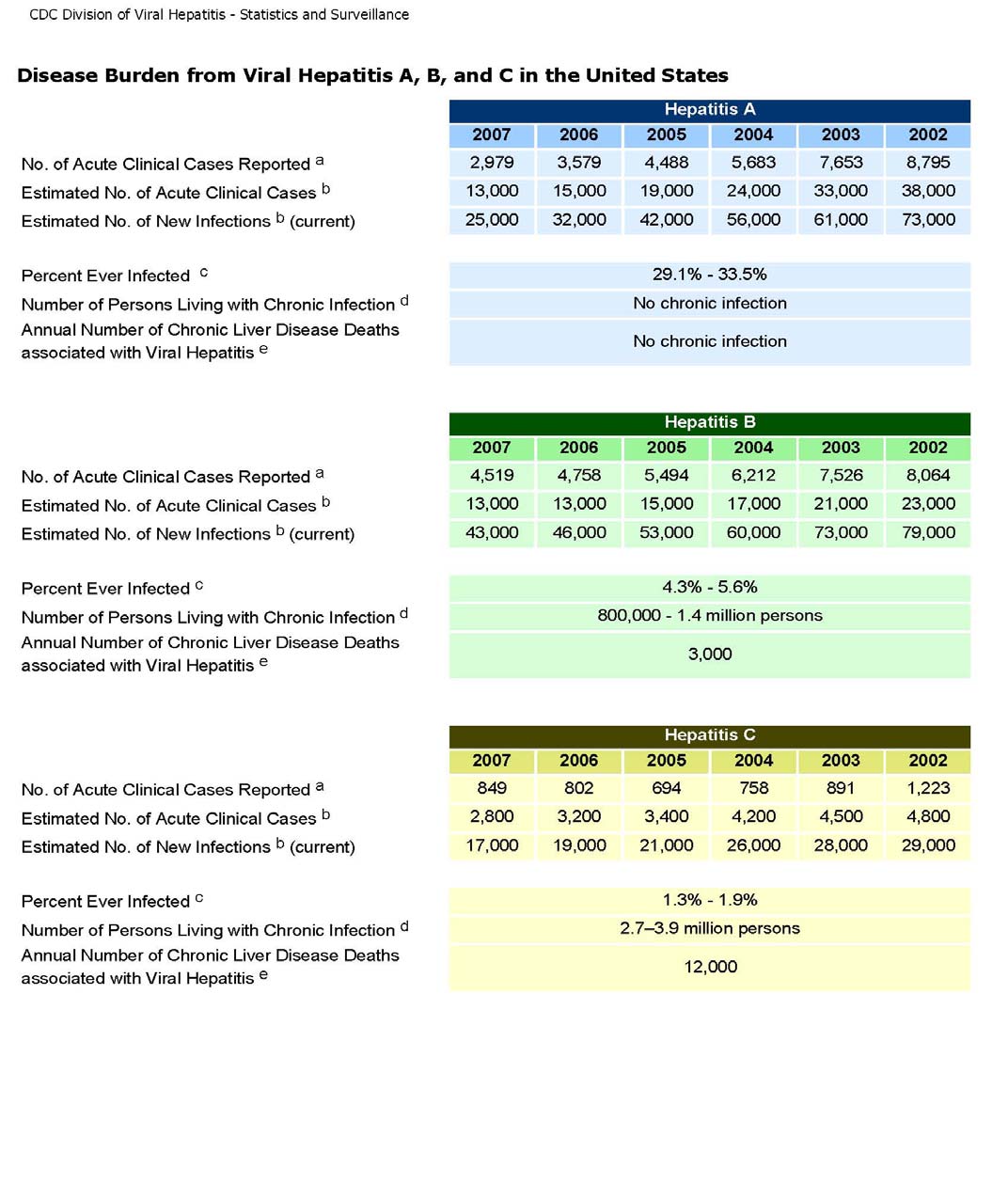

United States, approximately seven times more prevalent than HIV/AIDS (CDC Division

of Viral Hepatitis website).3 It has also become the leading cause of liver transplants due

to cirrhosis and one of the leading causes of liver cancer in the United States (American

Liver Foundation website).

Currently, there are approximately 3.2 million Americans living with chronic

HCV and 170 million cases of chronic HCV reported worldwide (CDC Division of Viral

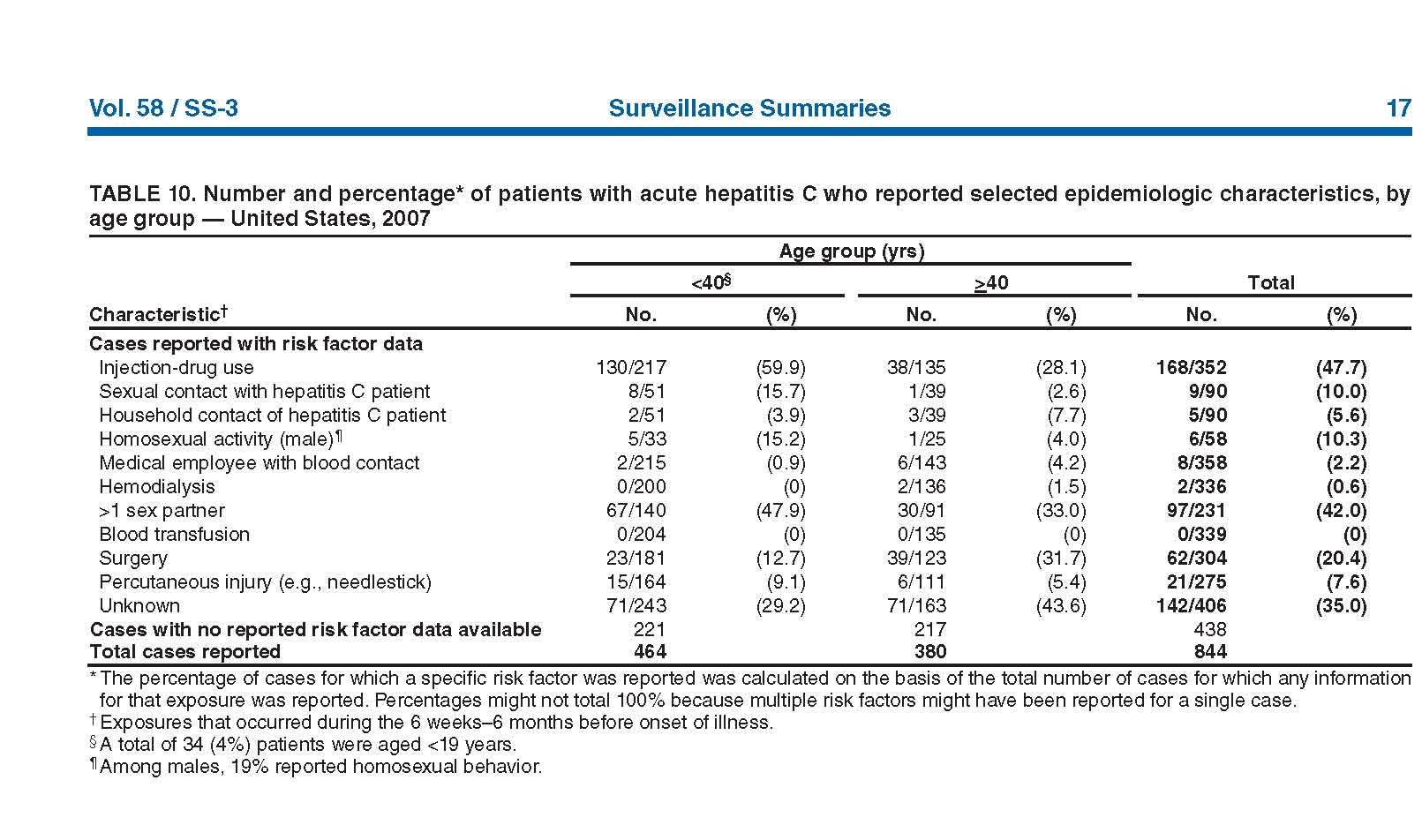

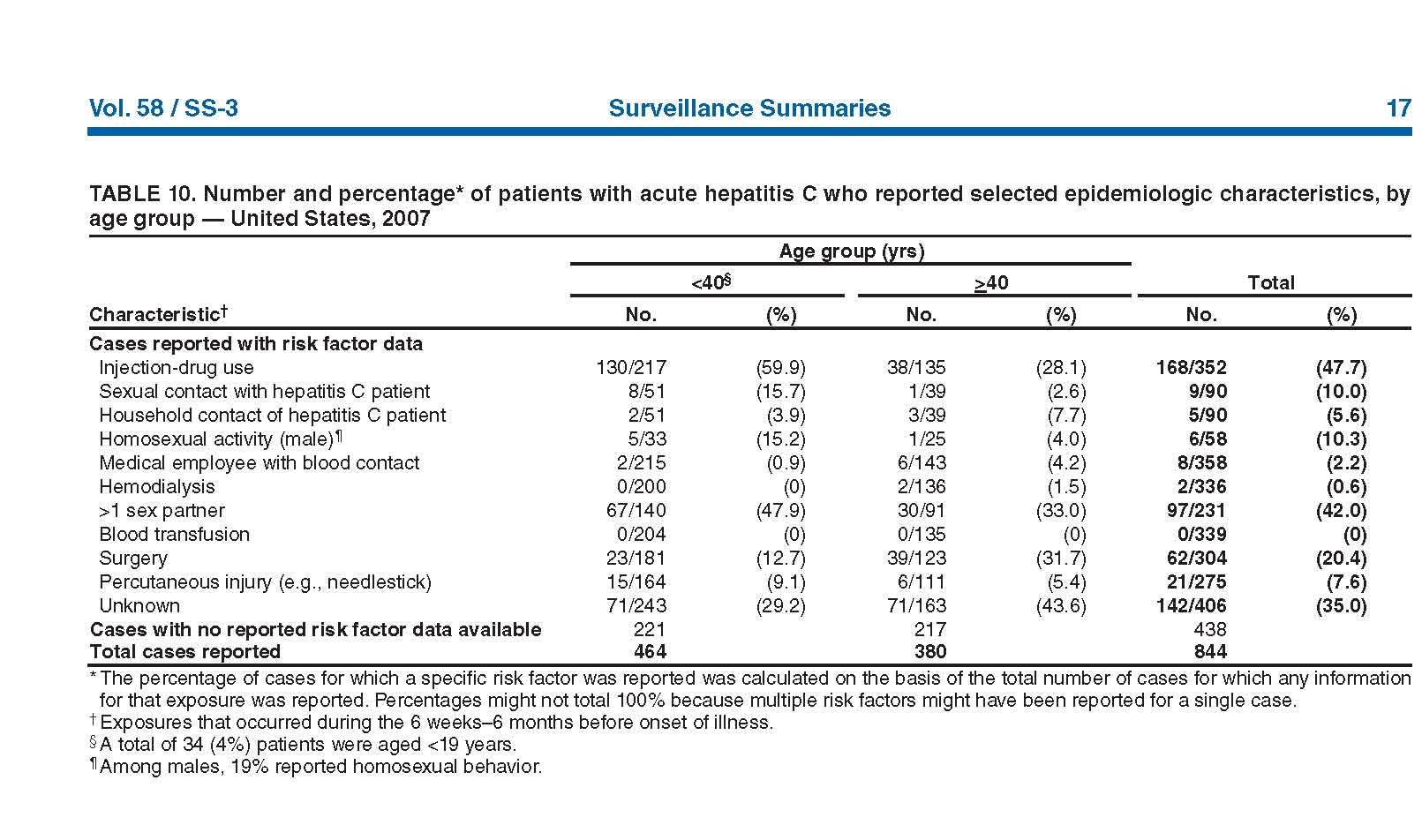

Hepatitis website) (Thomas et al. 450). Because HCV is a blood-born infection, HCV

patients consist mostly of current and past injection drug users (CDC Division of Viral

Hepatitis website). HCV can also be transmitted through tainted blood transfusions, use

of unsterilized medical equipment or personal hygiene items, and occasionally (less than

5% of the time) from mother-to-newborn baby. It is very rarely transmitted through

sexual contact (Hepatitis C Association website).4 Symptoms of HCV include fatigue,

fever, loss of appetite, nausea and vomiting, darkening of the urine, and jaundice (CDC

Division of Viral Hepatitis website). These symptoms are usually experienced by

patients in the acute stage of the disease. 15-25% of the time, however, the human body

is able to clear the virus naturally and patients can go on to live healthy and normal lives.

When the body does not clear the virus (75%-85% of the time), then the patient has

moved on to the chronic stage of the disease. It is at this point that progression to end-

stage liver disease (ESLD) becomes possible (CDC Division of Viral Hepatitis website).

The gold standard in testing for HCV is a liver biopsy, but testing can also be

done via blood samples (NIH Consensus Conference report S6-S7). Once a patient tests

positive for HCV, immediate lifestyle changes are encouraged, including the cessation of

3 Calculations are based on 2007 reports on both HCV and HIV infections in the United States. See Appendices A and B. 4 See <http://www.hepcassoc.org/Whatishepatitisc.html>

Patrick J. Walsh - 4

drinking alcoholic beverages or smoking tobacco, appropriate diet and exercise

regiments, and (if applicable) the cessation of the use of injection drugs or risky sexual

practices (Focus on Hepatitis C website).5 Additionally, a decision can be made on

whether or not treatment for the disease is necessary. In both the acute and chronic

stages, the most common forms of treatment for HCV are the medications pegylated

interferon and ribavirin (CDC Division of Viral Hepatitis website). If the disease

progresses into the chronic stage, as previously mentioned, further treatment may become

necessary for cirrhosis and liver cancer. Costs associated with both primary and

secondary treatments can approach tens of thousands of dollars (Pyenson et al. 23).

HCV shares many qualities with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) as well.

Both diseases share transmission vectors, virological composition, and target similar at-

risk populations. Co-infection of both diseases is also possible (Franciscus and

There is no vaccine available for treating HCV. There has been an effective HAV

and HBV vaccine developed in the 1990s (called Twinrix) that grants immunity to both

HAV and HBV after receiving all three doses (Food and Drug Administration website).

Research is still ongoing to create an effective HCV vaccine, however.

There is also an overpowering social stigma that exists surrounding blood-borne

infections in the United States and around the world. As previously mentioned, the

majority of current HCV patients are either current or former IDUs. Many IDUs living

5

Focus on Hepatitis C is a website constructed by the American Association for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence (AATOD) and the Hepatitis C Association (HCA). Funding for this website was made possible by a grant from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) within the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). See <http://www.hepcfocus.com/Content/AboutUs.aspx>

Patrick J. Walsh - 5

with the disease often do not seek treatment for their illness because their at-risk behavior

is frowned upon by healthcare providers.

Despite all of these facts and expert acknowledgement that HCV is a major global

public health issue, HCV is not on the legislative radars of public health officials in both

the United States and around the world.6 Until HCV becomes a political priority, then

the burden of the disease will continue to grow. This paper will explore both the science

and the politics surrounding the global burden of HCV and arrive at an informed policy

decision based on both empirical and normative inputs.

The literature reviewed for this paper consisted of scholarly articles from medical

journals as well as existing United States government reports and statistics. General

information about HCV was courtesy of the United States Center for Disease Control and

Prevention's Division of Viral Hepatitis website and the National Institute for Diabetes

and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). To address more specific topics, research

articles in scholarly journals as well as information gather by non-profit agencies were

To address the issue of global cases of HCV, the book

International Public

Health by Michael H. Merson et al. was consulted. Additionally, the website for the

United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention's Division of Viral Hepatitis

was also referenced. The information from these resources was first accessed on April 5,

2010. For worldwide statistics, the article "The Natural History of Hepatitis C Virus

6 As stated in Merson et al. 157.

Patrick J. Walsh - 6

Infection Host, Viral, and Environmental Factors," by David L. Thomas et al. was

referenced in addition to

International Public Health. The article can be found in the

Journal of the American Medical Association,

Volume 284, Issue 4, originally published

in July 2000. It was originally accessed on March 31, 2010. All of these resources were

selected because of the general and comprehensive information they gave regarding U.S.

and world HCV statistics. Links to the information used can be found in the Works Cited

section of this paper.

The articles "Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and

Control of Hepatitis B and C," edited by Heather M. Colvin and Abigail E. Mitchell,

"The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and

primary liver cancer worldwide," by Joseph F. Perz et al., and "Estimating Future

Hepatitis C Morbidity, Mortality, and Costs in the United States," by Dr. John B. Wong

et al. were examined to address the issues of end-stage liver disease and other liver

disease progression in the body as the result of HCV. The Colvin and Mitchell piece was

arranged by the Institute of Medicine at the National Academies. It was accessed on

April 21, 2010. The Perz piece can be found in the

Journal of Hepatology, Volume 45,

Issue 4, published October 2006. These pieces were used because of the information they

provided about the progression of liver disease in the human body. The Wong article

appears in the

American Journal of Public Health, Volume 90, Issue 12, published

October 2000. This article was accessed on April 21, 2010. Additionally, the Perz article

discusses statistics from a global perspective while the Colvin and Mitchell and Wong et

al. pieces only describe statistics from the United States. Links to both works can be

found in the Works Cited section of this paper.

Patrick J. Walsh - 7

To address the issue of the cost of treatment for HCV, the article by Wong et al.

was consulted again as well as data from "Consequences of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV):

Costs of a Baby Boomer Epidemic of Liver Disease," by Pysenson et al. were consulted.

The Pysenson article was accessed on April 4, 2010 from Milliman Incorporated's

website. Information regarding treatment response rates and who should seek treatment

was provided by NIDDK within the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This

information was accessed on April 24, 2010. All of these resources were chosen because

of the information they provided about not just the cost of treatment for HCV but also the

types of treatments that are available for persons living with HCV as well as who should

seek treatment once becoming infected. Links to all of this information is available in the

Works Cited section.

Another important research area surrounding HCV is the development of an

effective vaccine. The Colvin and Mitchell article discusses this topic in detail, but the

article "Hepatitis C vaccine: supply and demand," by G. Thomas Strickland et al. was

also reviewed. This article was accessed on April 21, 2010 and appears in the journal

The Lancet—Infectious Diseases, Volume 8, Issue 6, published in June 2008.

Additionally, a statement from the NIH consensus conference on HCV management was

also consulted. This statement appears in the November 2002 issue of

Hepatology and

was accessed on April 12, 2010. Links to both of these pieces can be found in the Works

As previously mentioned, HCV also shares many qualities with HIV because they

are both blood-born infections. To further research this, the article "HIV/HCV

Coinfection," by Alan Franciscus and Liz Highleyman was consulted. This fact sheet

Patrick J. Walsh - 8

appears on the website HCV Advocate and it was accessed on April 22, 2010. Materials

from the CDC Division of Viral Hepatitis and Health Resources and Services

Administration (HRSA) were also referenced and accessed on April 24, 2010. These

articles were selected because of the wealth of information they provided regarding

coinfection of these two very similar diseases. Links to these materials can be found in

the Works Cited section of the paper.

Finally, to address the issue of stigma associated with HCV worldwide, the article

"Illness-related stigma, mood and adjustment to illness in persons with hepatitis C," by

Jeannette Golden et al. was consulted. This article was accessed on April 15, 2010 and

appears in the journal

Social Science and Medicine, Volume 63, Issue 12, originally

published in December 2006. This article was selected because it is one of the few

articles that speaks to specific stigma experienced by persons in HCV treatment.

Additional information was used from Colvin and Mitchell. A link to this article can be

found in the Works Cited section of this paper.

When all of these factors are considered, a policy decision regarding the status of

hepatitis C virus as a global public health emergency can be decided.

Results and Discussion:

As previously mentioned, CDC statistics indicate that there are 3.2 million

Americans living with chronic HCV and 17,000 new cases reported each year in the

nation. The global number of chronic HCV infections is 170 million according to World

Health Organization (WHO) 1997 statistics (qtd. in Merson et al. 158) The WHO adds

that the prevalence of infections, again by the 1997 statistics, seems to be concentrated in

Patrick J. Walsh - 9

central and north African nations (such as Egypt and Sudan), central Asian nations (such

as Mongolia), and South American nations (such as Bolivia and Brazil) (qtd. Merson

159).7 The CDC estimates, however, that less than half of these new infections ever

become diagnosed and reported (CDC Division of Viral Hepatitis website).8 Although

the numbers of new infections have decreased dramatically since the 1980s, unreported

cases still remain a nagging issue. The primary reason for new cases going

undocumented is because HCV is often an asymptomatic disease. This means that a

newly infected patient can look and feel fine, but still have the virus present in his or her

body (CDC Division of Viral Hepatitis website). The CDC also reports that even acute

cases of HCV, where symptoms are present, can even go unreported to public health

authorities (see Appendix B).

Even with the raw numbers known, this still insufficient evidence for arguing that

HCV is a policy priority. The reason is because the majority of new HCV infections can

potentially go unreported, and as a result, the number of cases is severely

underrepresented (as seen in Appendix B). This fact could be a major determining factor

in why HCV is not considered a public health priority. Building on this, HCV is also a

virus that the human body is capable of clearing naturally, and this could be another

argument against HCV as a global public health threat. When the human body clears a

disease, the immune system is able to fight off chronic infection of the virus and the

patient can go on to live a health and normal life (California Pacific Medical Center

website). At the same time, this newly infected person may not have ever experienced

any symptoms of HCV. With insufficient concrete evidence to support the politics of in

7 This data reported in Merson et al. was provided by the World Health Organization. 8 The number of clinical cases reported in 2007 was 849 plus an estimation of 2,800 new acute clinical cases. See Appendix B.

Patrick J. Walsh - 10

favor of HCV legislation, no policy decision can be arrived at looking at just raw

Despite patients not experiencing any symptoms, HCV infection can still amplify

the progression of end-stage liver disease (as seen in 60-70% of patients). The most

common of these ESLDs is liver cirrhosis (as seen in 5-20% of patients). Liver cirrhosis

is a scarring of healthy liver tissue to the point where the liver ceases to function properly

(American Liver Foundation website). Cirrhosis can also be acquired as the result of

long-term alcohol abuse, which is why the cessation of alcohol use is strongly advised

once a patient becomes infected with HCV (NIDDK website). Perz et al. state that 32%

of liver cirrhosis cases worldwide are the result of alcohol abuse and approximately 27%

of cases are caused by HCV (534). Hepatocellular carcinoma (or HCC, a variety of liver

cancer) is the next progression stage of ESLD and is seen in as seen in 1-5% of HCV

patients (CDC Division of Viral Hepatitis website). According to Perz et al.,

approximately 25% of all liver cancer cases worldwide are attributed to HCV (534). Perz

et al. also report, however, that progression to HCC does not require the presence of liver

cirrhosis in a patient (529). Additionally, Colvin and Mitchell state that approximately

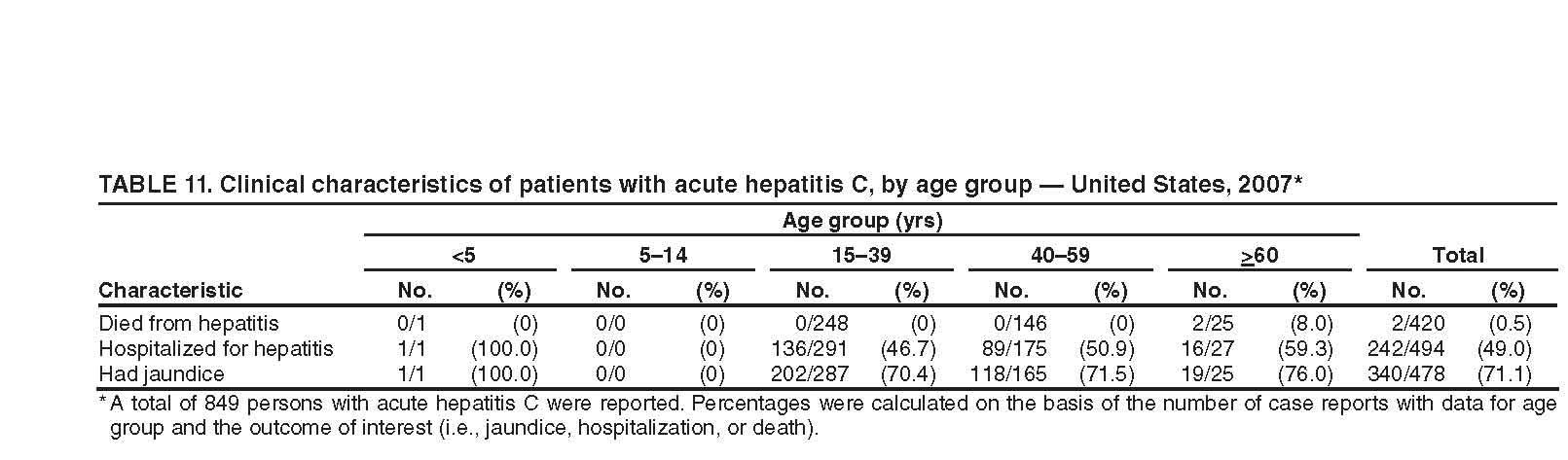

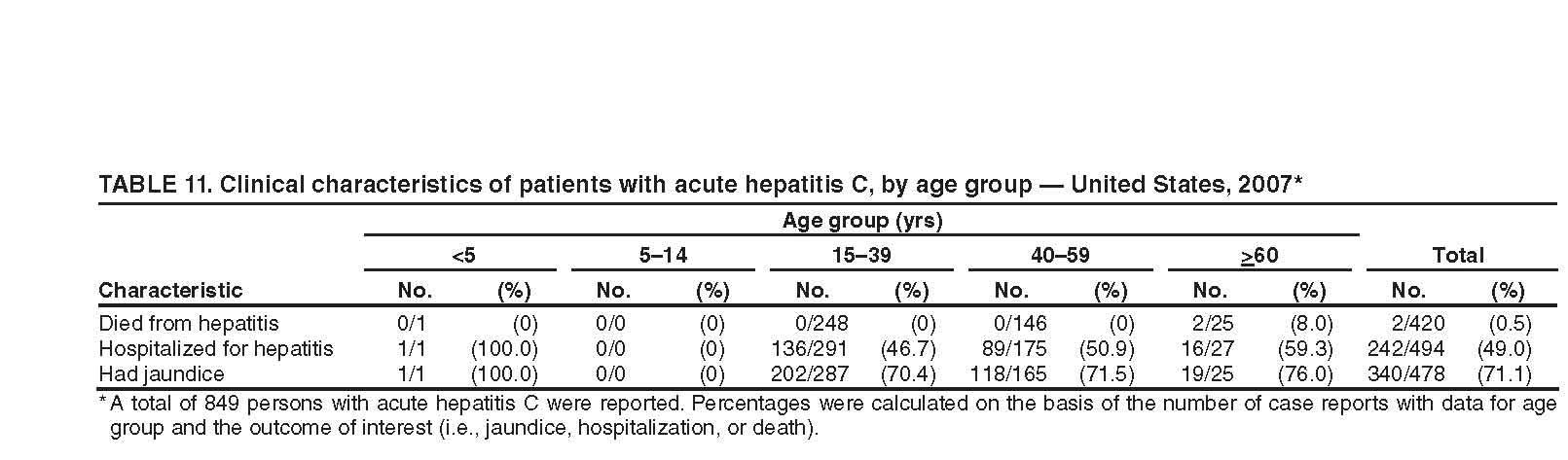

12,000 Americans die from complications due to HCV each year (23-24).

In this particular case, two other chronic and equally deadly diseases are aided in

their progression by the presence of HCV. The fact is, however, that many patients who

progress to chronic liver cirrhosis and HCC are more likely to die as a result of these

diseases than they are complications from HCV infection. In other words, patients are

more likely do die with HCV rather than from HCV (CDC Division of Viral Hepatitis

Patrick J. Walsh - 11

report).9 Because of this, the global morbidity rate for HCV will be significantly lower

than it actually is. At the same time, however, cirrhosis and HCC statistics will remain

well represented, as Wong et al. suggest (1562). Additionally, as Perz et al. have

reported, more cases of liver cirrhosis are the result of long-term alcohol abuse instead of

HCV (534). This is another reason against the case for HCV as a policy priority.

Because data show that alcohol abuse is a larger contributing factor to the progression of

ESLD than HCV around the world, more social and financial resources can potentially

become dedicated to managing cirrhosis as the result of alcohol abuse rather than

managing cirrhosis as a result of HCV. Perz et al. continue to say that the results of their

study provide further evidence for the allocation of resources for HCV management

programs at the national level (535).

There are a variety of treatment options available for chronic HCV patients. The

most common pharmaceuticals that are used for treatment are alpha pegylated interferon

and ribavirin (Food and Drug Administration website). Both of these drugs are

manufactured by the Roche Corporation and are sold in the pharmaceuticals market under

the names "Pegasys" (pegylated interferon) and "CoPegus" (ribavirin) (FDA website).10

Additionally, each of these drugs carries their own side effects, including flu-like

symptoms, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, headaches, and loss of appetite (Pegasys website).

As patients progress on to ESLD, however, treatments become more and more

complicated and expensive. According to Pyenson et al., the cost of treating liver

cirrhosis can range from just over $4,000 a patient to over $12,000. Additionally, the

cost of a liver transplant can range from $25,000 to $38,000 depending on individual

9 Please refer to Appendix C. 10 No market prices were available for these drugs in any consulted scholarly sources.

Patrick J. Walsh - 12

cases (Pyenson et al. 23). Elderly patients are eligible to receive testing and treatment as

part of their Medicare benefits as well (Colvin and Mitchell 124). Wong et. al. report that

treating HCC costs $33,000 annually (1565).11

There are also conflicting factors as to which populations of people receive what

kinds of treatment and for how long. According to NIDDK's website, "Patients with

anti-HCV, HCV RNA, elevated serum aminotransferase levels, and evidence of chronic

hepatitis on liver biopsy, and with no contraindications…" should receive treatment for

HCV. NIDDK adds that HCV is a virus that will interact with different human genotypes

differently. Patients who are genotypes 1 and 4 typically receive 48 week treatment

cycles with pegylated interferon and ribavirin whereas persons who are genotypes 2 and

3 receive approximately 24 weeks of treatment with the same dosages of the same drugs

(NIDDK website). The reason for this difference is the response rate of each particular

genotype; some bodies just respond better to treatments regardless of disease progression.

Moreover, NIDDK adds on their website that response rates are better in particular ethnic

groups (such as Caucasians and Asians) than others (Africans). A source from the

National Center for Biotechnology Information adds that immunization against HAV and

HBV is a vitally important treatment step as well (Lo Re III et al. 6).

These mixed messages regarding who should receive treatment and for how long

could also be reasons why HCV is not treated as a top public health policy issue. The

world is receiving very confusing information about genotypes and what treatment

priorities for HCV are. This information could potentially be translated as racially biased

against particular ethnic groups. Moreover, the costs of treatments are extremely high for

treatments beyond pegylated interferon and ribavirin, as Pyenson et al. and Wong et al. 11 Dollar figures are estimated in 1999 dollars.

Patrick J. Walsh - 13

have reported. No such invasive tests and treatments, such as a liver biopsy or liver

transplant, are required for the diagnoses of other chronic infectious diseases such as

HIV. Strickland et al. go on to add that this therapy of pegylated interferon and ribavirin

is often a "curative method," meaning that these drugs aid in clearing the virus from the

There is currently no vaccine available for HCV prevention and treatment despite

the presence of a very effective vaccine for HAV and HBV (as previously mentioned).

According to Dr. Allan Morrison, the prevailing reason for the lack of a vaccine for HCV

is because of the nature of the hepatitis C virus. It is a single-stranded RNA virus (a

flavivirus) and therefore is constantly evolving and mutating. Because of its constantly-

changing composition, no successful vaccine has yet been developed to combat HCV

infection.12 The NIH Consensus Conference on HCV Management held in 2002 names

identifying a vaccine for HCV as the top priority for HCV research (NIH Consensus

Conference statement ). This attitude is also reflected in Colvin and Mitchell's report,

indicating that a vaccine would "…substantially enhance hepatitis C prevention efforts"

(112). Strickland et al. mention in their study that six HCV vaccines currently in clinical

trials as of 2008. The majority of these vaccines have been tested on primate populations

and some of the vaccines the authors mention will soon be tested on chronically infected

HCV patients (381-382).

Although an effective vaccine is being researched and developed at this time, this

is still not a convincing argument for lawmakers to consider HCV a top public health

policy priority. Colvin and Mitchell argue that there is not enough incidence of HCV

12 Dr. Allan Morrison was a guest lecturer at George Mason University's School of Public Policy on March 16, 2010. His lecture was entitled "Vaccine Development, Administration, Public Health Policy, Politics, and Commerce."

Patrick J. Walsh - 14

(going back to the fact that new cases often go unreported) to justify universal

vaccinations (112). Moreover, they add that the populations that would receive the

greatest benefit from an HCV vaccine would be the high-risk populations of injection

drug users (IDUs) and men who have sex with other men (MSMs) (112).13 Because a

vaccine would benefit these extremely controversial individuals, lawmakers are likely to

ignore the issue of the development of a vaccine despite the benefit it could give to the

global population of persons living with HCV.

HIV infections are far less prevalent worldwide than HCV infections despite the

diseases being very similar (CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly report).14 Both HIV

and HCV are contracted by blood-to-blood transmission, both are single-strand (RNA)

viruses, and there is neither a vaccine nor a cure for either disease. Additionally, these

diseases are also a public health risk within populations of IDUs. The sharing of used

syringes is a common practice with IDUs, and therefore this specific population is at a

higher risk for infection with either disease than any other population (Franciscus and

Highleyman 1). Other groups that are highly at-risk for HIV/HCV co-infection are

MSMs and people who engage in unsafe or other rough sexual practices where blood-to-

blood contact is possible, but rare (Focus on Hepatitis C website). Moreover, Franciscus

and Highleyman add that treating coinfection further complicates problems of which

treatment takes precedence. For example, the authors explain that many HIV

medications are processed through liver tissue and can cause additional liver toxicity (1-

13 According to the CDC, the term "MSM" applies to any man who has had sexual contact with other men regardless of sexual preference. See <http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/msm/> 14 According to 2006 data collected by the CDC, the approximate number of HIV cases worldwide was estimated at 65 million persons living with the disease. This data was collected by the World Health Organization. See <http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5531a1.htm>

Patrick J. Walsh - 15

Unlike HIV, though, HCV has remained off of many nations' public health

legislation radars for a variety of reasons. In the case of the United States, one possible

reason is because more activism has been performed to benefit HIV legislation than HCV

legislation. An example can be seen in the Ryan White CARE Act of 1990. This

program, funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) within

HHS, provides funding for public health entities in the country for the treatment and

education of HIV/AIDS. It has been reauthorized three times, most recently in 2006, and

has been renamed the "Ryan White HIV/AIDS Treatment Modernization Act" (HRSA

website). Its namesake is a teenaged HIV activist who was denied the right to attend

school after testing positive for HIV after receiving a blood transfusion (HRSA website).

Hepatitis C has not received this level of passionate lobbying, although the lobbying

community within the HCV policy realm is extremely close knit and extremely

knowledgeable.15 Because HIV has had this extremely personal story told, Federal

legislation and funding has been passed to greatly benefit research, education, and

outreach for HIV infections. Franciscus and Highleyman add that "More research and

education for both doctors and patients is needed before we can fully understand how

both these diseases work in the body" (2).

Many treatments are not accessible to some populations of HCV patients,

however. For example, Colvin and Mitchell report that HCV has a prevalence rate of

30%-70% in populations of injection drug users and 12%-35% in correctional settings

(141-148). These groups are already under a tremendous amount of stigma for their

behaviors that they often do not seek treatment for HCV infections. As Golden et al.

15 Such groups include the Hepatitis C Association (www.hepcassoc.org), the National Viral Hepatitis Roundtable (www.nvhr.org), and the Hepatitis Education Project (www.hepeducation.org).

Patrick J. Walsh - 16

argue, "…diagnosis of hepatitis C appears to be particularly psychologically painful and

is associated with high levels of anxiety…" (3194) This implies that IDUs or prison

inmates will have a fearful or shameful attitude towards caregivers and believe that they

will be chastised or turned away as a result of their sustained at-risk behavior. Golden et

al. also report that:

…current and former injecting drug users, has an increased risk of psychiatric disorder independent of hepatitis C status, due both to their socio-demographic characteristics and to the high prevalence of antisocial personality disorder which is a risk factor for both mood disorder and for hepatitis C. (3194)

Again, this implies a powerful stigma that this high-risk and high rate of infection group

of people. A specific example can be found in the Colvin and Mitchell piece, where the

authors describe that drug use in the "Golden Triangle" region of China is extremely

stigmatized. In this part of China, drug users are afraid to seek treatment for their habits

because they fear social and legal repercussions (20). The authors continue to report that

discriminatory treatment of HCV is common, but that "…this discrimination is more

marked in those who also carry the stigma of injecting drug use…" and not from those in

the medical profession (3195).

Again, an ethical issue is raised with the decision to treat high-risk populations for

infectious disease. Contrary to what IDUs or MSMs might believe, and as Golden et al.

reinforce in their argument, medical professionals are willing to provide care for

members of these populations. The stigma that continues to overpower these groups,

however, is what prevents HCV from becoming a policy priority. If legislation were

taken up to benefit these groups, especially if these groups were the intended

beneficiaries of the policy, lawmakers would be in an extremely compromising position.

Patrick J. Walsh - 17

As long as the persons who are most at risk for this disease do not seek treatment for it

because of their stigmas, then public policies to benefit all persons living with chronic

HCV will never develop.

Conclusion and Policy Implications:

Although controversial, HCV must be brought to the forefront of public health

legislation in nations all over the world. When considering incidence and prevalence

rates higher than those of HIV, the other chronic diseases that HCV can aid in

progressing, the increasing cost of treating the disease, the research needed for a

preventative vaccine, the close resemblance to HIV, and the overpowering social stigma

experienced by patients, more public policies are needed to relieve the global burden of

the disease. As it is clearly and repeatedly acknowledged by experts as a major global

public health risk, more public policies to benefit treatment, research, education, and

outreach on hepatitis C virus is desperately needed. The fact of the matter is, however,

that this disease is not treated as the priority is has become. The National Institutes of

Health Consensus Conference Statement even goes as far to say that more education and

awareness is needed in American schools (S13).

For the reasons discussed previously and more, HCV is not treated by lawmakers

as a global public health threat. The passage of public policies to benefit HCV programs

carries a high number of caveats and contingencies. For example, if the largest

beneficiary of HCV legislation all over the world will be IDUs, then nations would have

to change their policies on enforcement existing drug laws (Strathdee and Vlahov 4).

This could mean the legalization of narcotics that are currently considered illicit and

frequently used by IDUs (such as cocaine and heroin). Another implication of this new

Patrick J. Walsh - 18

HCV policy could be changes to the way HCV is treated within these populations. The

article "Methadone maintenance and hepatitis C virus infection among injecting drug

users," by N. Crofts et al. mentions that 66.7% of over 1700 IDUs treated at Australian

methadone maintenance programs from 1991-1995 tested positive for HCV antibodies

(abs.) Therefore, methadone maintenance programs could potentially receive more

public funding as a source of treatment for IDUs living with HCV. At the same time,

however, this also means that resources and funding must also be diverted from research,

outreach, education, and policies from other equally important public health issues.

Moreover, additional funding for HCV programs at a global level could

potentially divert funding from other equally necessary and needed health programs. For

example, Colvin and Mitchell report that 2% of the CDC's National Center for

HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, Sexually Transmitted Disease, and Tuberculosis Prevention's

(CDC NCHHSTP) budget from 2008 was dedicated to HCV programs whereas 69% of

the center's budget was allocated for HIV programs (21).

The best public policies, as students are taught at George Mason University's

School of Public Policy, are formulated when lawmakers combine empirical evidence

and normative values. This is particularly the case with HCV legislation, where a

debilitating and chronic illness is infecting a silent majority of people around the world.

Ideally, each person living with HCV would be able to receive the same amount of

treatment and care than any other person living with a chronic illness, but the legislation

and policies to make this possible do not exist. As additional research and education are

performed to benefit viral hepatitis C, perhaps the international public health community

will give HCV the attention it so desperately needs.

Patrick J. Walsh - 19

Works Cited

American Liver Foundation.

Liver Transplant. 28 Sept. 2007. 6 Apr. 2010. <http://www.liverfoundation.org/education/info/transplant/> -------------

Glossary. 28 Sept. 2007. 6 Apr. 2010. <http://www.liverfoundation.org/popup/glossary.php#c> Cooper, Stewart. California Pacific Medical Center.

Hepatitis C Virus and the Human Immune System. 23 Nov. 2009. 18 Apr. 2010. <http://www.cpmc.org/advanced/liver/news/newsletter/livrev-cooper1005.html> Colvin, Heather M. and Abigail E. Mitchell, eds. "Hepatitis and Liver Cancer: A National Strategy for Prevention and Control of Hepatitis B and C." Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2010. <http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=12793#toc> Crofts, N. et al. "Methadone maintenance and hepatitis C virus infection among injecting drug users."

Addiction 92 (1997): 999-1008.

Research Databases. IntegaConnect. George Mason University, Arlington 29 Apr. 2010 <http://www.ingentaconnect.com.mutex.gmu.edu/search/article?title=Methadone+maintenance+and+hepatitis+C+virus&title_type=tka&author=crofts&year_from=1998&year_to=2009&database=1&pageSize=20&index=1> Focus on Hepatitis C.

Are You At Risk? 19 May 2009. 10 Apr. 2010 <http://www.hepcfocus.com/content/Areyouatrisk.aspx> Franciscus, Alan and Liz Highleyman "HIV/HCV Coinfection."

Hepatitis C Advocate. 1 Mar. 2010. 22 Apr. 2010. <http://www.hcvadvocate.org/hepatitis/factsheets_pdf/HIV_HCV%20coinfecton_10.pdf> Golden, Jeannette et al. "Illness-related stigma, mood and adjustment to illness in persons with hepatitis C."

Social Science and Medicine 63 (2006) 3188-3198.

Research Databases. Science Direct. George Mason University, Arlington 15 Apr. 2010 Hepatitis C Association.

About Us. 30 July 2009. 10 Apr. 2010. <http://www.hepcassoc.org/Aboutus.html> -------------.

What is Hepatitis? 30 July 2009. 10 Apr. 2010. <http://www.hepcassoc.org/Whatishepatitisc.html> Lo Re III, Vincent et al. "Management Complexities of HIV/HCV Coinfection in the Twenty-First Century."

Clin Liver Dis 12 (2008): 587-ix.

Patrick J. Walsh - 20

Marco, Michael. "Epidemiology, Modes of Transmission, and Risk Factors for Hepatitis C Virus."

Treatment Action Group. 14 July 2000. 10 Apr. 2010. <http://www.thebody.com/content/art1696.html> Merson, Michael H et al., eds.

International Public Health. 2nd ed. Sudbury: Jones and Bartlett Publishers, 2006. Perz, Joseph F. et al. "The contributions of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections to cirrhosis and primary liver cancer worldwide."

Journal of Hepatology 45 (2006): 529-538.

Research Databases. Science Direct. George Mason University, Arlington 21 Apr. 2010 <http://www.sciencedirect.com.mutex.gmu.edu/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6W7C-4K7X85R-3&_user=650615&_coverDate=10%2F31%2F2006&_alid=1305155915&_rdoc=1&_fmt=high&_orig=search&_cdi=6623&_sort=r&_docanchor=&view=c&_ct=1&_acct=C000035118&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=650615&md5=86692a6a3b5ae12e7f92f7cfeae74c59> Pyenson, Bruce et al. "Consequences of Hepatitis C Virus (HCV): Costs of a Baby Boomer Epidemic of Liver Disease."

Milliman Inc. Google Scholar. George Mason University, Arlington 4 Apr. 2010 <http://www.milliman.com/expertise/healthcare/publications/rr/pdfs/consequences-hepatitis-c-virus-RR05-18-09.pdf> Roche Corporation, The.

Hepatitis C Treatment Side Effects. 1 May 2009. 25 Apr. 2010 <http://www.pegasys.com/about-pegasys/side-effects.aspx> Strathdee, Steffanie A. and David Vlahov. "The effectiveness of needle exchange programs: A review of the science and policy."

AIDS Science 1.16 (2001). Google Scholar. George Mason University Library, Arlington, VA. 30 Mar. 2010 <http://198.151.217.81/Articles/aidscience013.pdf> Strickland, Thomas G. et al. "Hepatitis C vaccine: supply and demand."

The Lancet 8 (2008): 379-386.

Research Databases. Science Direct. George Mason University, Arlington 12 Apr. 2010 <http://www.sciencedirect.com.mutex.gmu.edu/science?_ob=MImg&_imagekey=B6W8X-4SK0K94-V-1&_cdi=6666&_user=650615&_pii=S1473309908701269&_orig=search&_coverDate=06%2F30%2F2008&_sk=999919993&view=c&wchp=dGLzVtz-zSkzS&md5=c6aeef675d4c8beda66e469c1331752d&ie=/sdarticle.pdf> Thomas, David L. et al. "The Natural History of Hepatitis C Virus: Host, Viral, and Environmental Factors."

Journal of the American Medical Association 284 (2000): 450-456.

Patrick J. Walsh - 21

United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

CDC Division of Viral Hepatitis—FAQs for Health Professionals. 21 July 2008. 5 Apr. 2010 <http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HCV/HCVfaq.htm#section1> ------------- Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

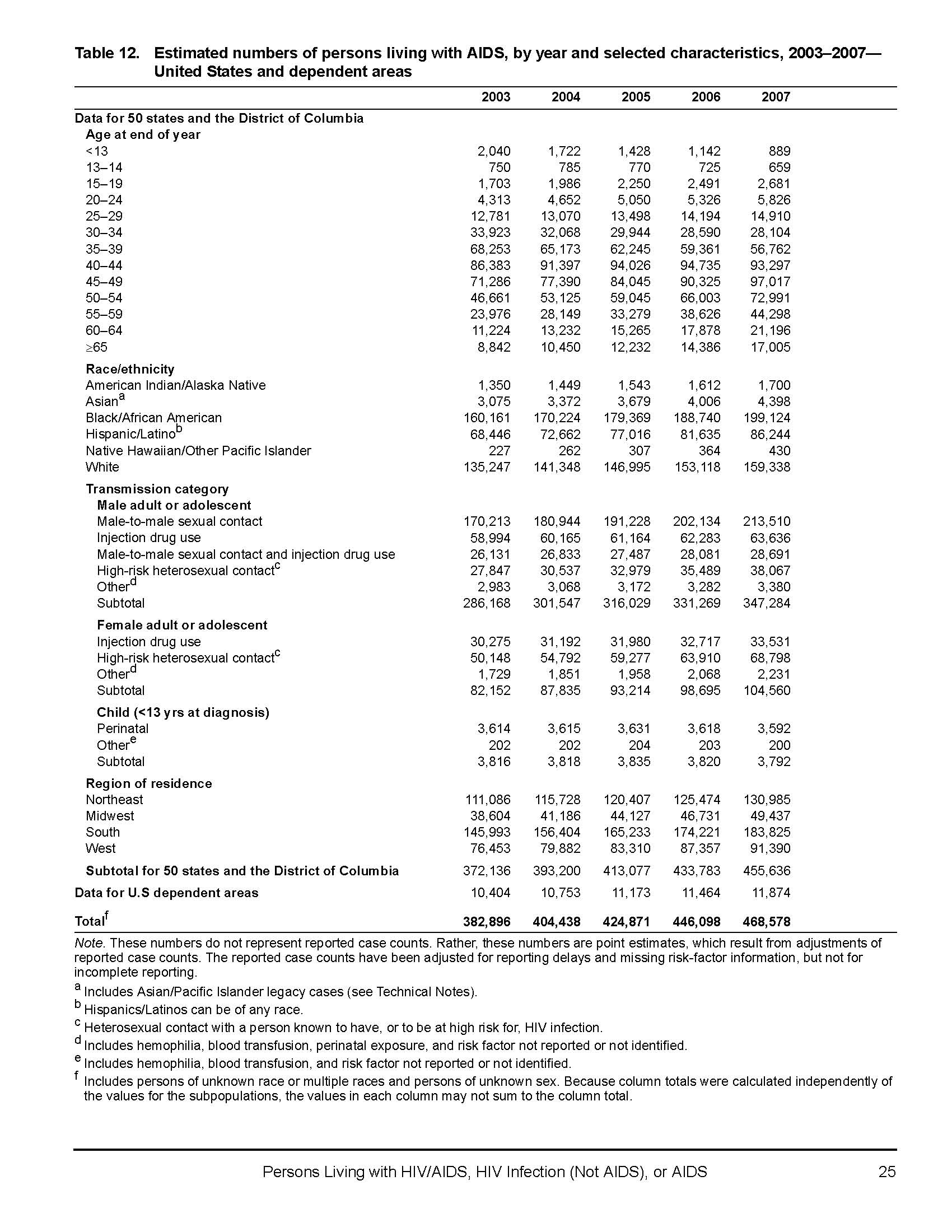

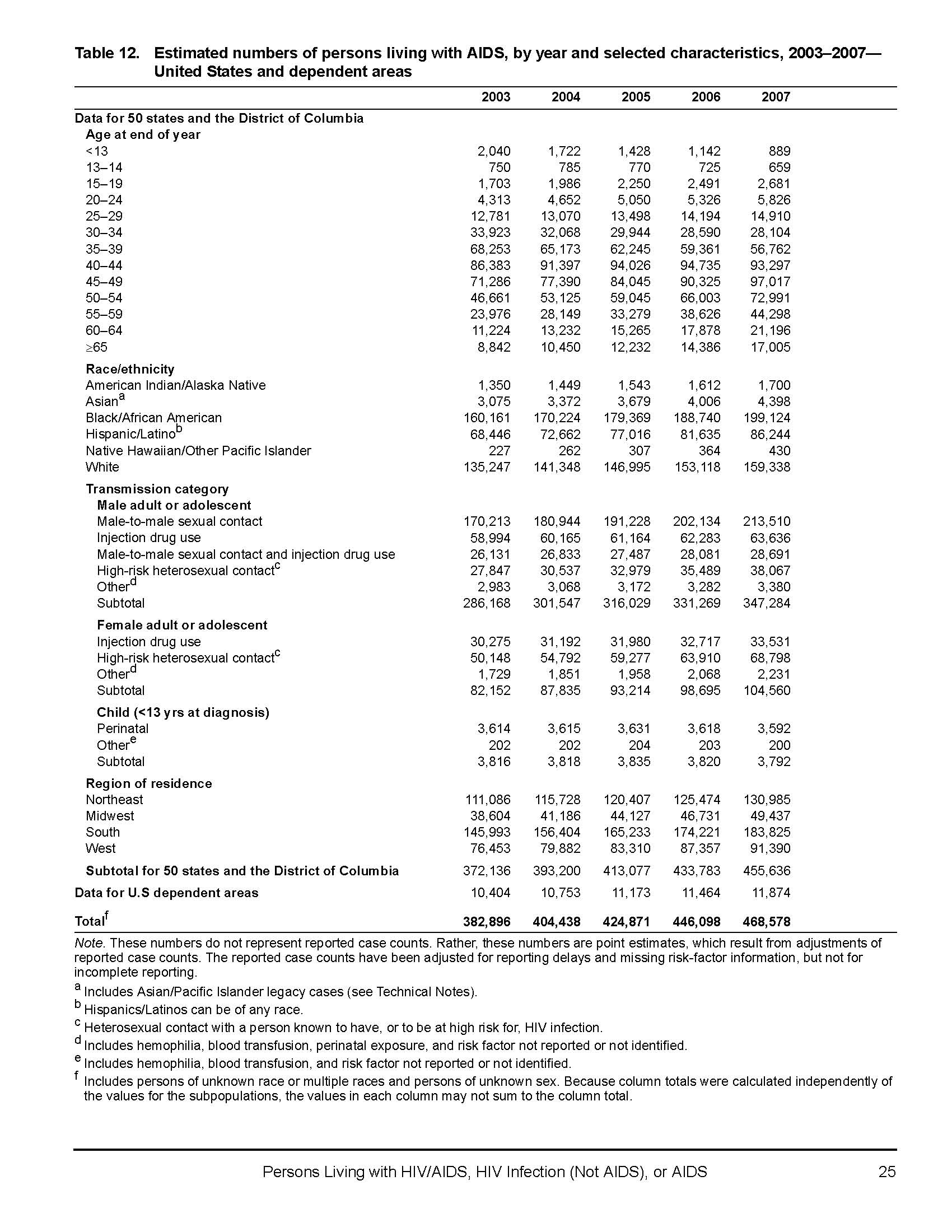

"Estimated numbers of persons living with AIDS, by year and selected characteristics, 2003–2007—United States and dependent areas." 19 Feb. 2009. 24 Apr. 2010. <http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/2007report/table12.htm> ------------- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

HIV/AIDS and Men Who Have Sex With Other Men. 30 Mar. 2010. 24 Apr. 2010. <http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/msm/> ------------- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The Global HIV/AIDS Pandemic, 2006. 11 Aug 2006. 24 Apr. 2010. <http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5531a1.htm> ------------- Food and Drug Administration.

Twinrix. 11 Dec. 2009. 10 Apr. 2010. <http://www.fda.gov/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/ucm094035.

htm> ------------- Food and Drug Administration.

Viral Hepatitis Therapies. 19 May 2009. 10 Apr. 2010. <http://www.fda.gov/ForConsumers/ByAudience/ForPatientAdvocates/ucm151494.htm> ------------- Health Resources and Services Administration.

HIV/AIDS Program. 8 Apr. 2009. 24 Apr. 2010<http://hab.hrsa.gov/law/leg.htm> ------------- National Institutes of Health.

National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference. "National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: Management of Hepatitis C."

Hepatology 36 (2002): S3-S20. 12 Apr. 2010 <http://consensus.nih.gov/2002/2002HepatitisC2002116main.htm> ------------- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Chronic Hepatitis C: Current Disease Management. 1 Nov. 2006. 24 Apr. 2010. <http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/chronichepc/> Wong, John B. et al. "Estimating Future Hepatitis C Morbidity, Mortality, and Costs in the United States."

American Journal of Public Health 90 (2000): 1562-1569. Google Scholar. George Mason University, Arlington 21 Apr. 2010 <http://ajph.aphapublications.org/cgi/reprint/90/10/1562>

Patrick J. Walsh - 22

Appendix A

Patrick J. Walsh - 23

Appendix B

Patrick J. Walsh - 24

Appendix C

Patrick J. Walsh - 25

Patrick J. Walsh - 26

Source: http://csimpp.gmu.edu/pdfs/student_papers/2010/Walsh2010.pdf

Smoking Cessation Pilot Program Oral Health Therapist Aim of this session • Increased awareness of cigarette smoking statistics • Improved knowledge of smoking cessation products and aids • How to implement a smoking cessation program Smoke Free at North Richmond • March 2015 City of Yarra grant to provide smoking cessation intervention to those ready to quit

CHRISTINE M. HEIM CHRISTINE MARCELLE HEIM Curriculum Vitae OFFICE ADDRESS Institute of Medical Psychology Charité Center for Health and Human Sciences Charité University Medicine Berlin Tel: +49 (0)30 450 529 221 Fax: +49 (0)30 450 529 990 CURRENT POSITIONS AND AFFILIATIONS Professor (W3) and Director of Institute of Medical Psychology, Charité Center