Thermografie-centrum.nl

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached

copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research

and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution

and sharing with colleagues.

Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or

licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party

websites are prohibited.

In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the

article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or

institutional repository. Authors requiring further information

regarding Elsevier's archiving and manuscript policies are

encouraged to visit:

Author's personal copy

Infrared Physics & Technology 52 (2009) 42–47

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Infrared Physics & Technology

Normalized methodology for medical infrared imaging

J.V.C. Vargas a,*, M.L. Brioschi a, F.G. Dias b, M.B. Parolin c, F.A. Mulinari-Brenner d, J.C. Ordonez e, D. Colman c

a Programa de Pós-Graduação em Engenharia Mecânica, Departamento de Engenharia Mecânica, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, PR, 81531-980, Brazilb Programa de Pós-Graduação em Engenharia, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, PR, 81531-980, Brazilc Transplante Hepático, Hospital de Clínicas da Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, Paraná, 80060-160, Brazild Departamento de Medicina Interna, Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, Paraná, 80060-160, Brazile Center for Advanced Power Systems and Department of Mechanical Engineering, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL 32310, USA

A normalized procedure for medical infrared imaging is suggested, and illustrated by a leprosy and hep-

Received 7 August 2008

atitis C treatment follow-up, in order to investigate the effect of concurrent treatment which has not been

Available online 7 December 2008

reported before. A 50-year-old man with indeterminate leprosy and a 20-year history of hepatitis C wasmonitored for 587 days, starting from the day the patient received treatment for leprosy. Standard ther-

apy for hepatitis C started 30 days later. Both visual observations and normalized infrared imaging were

conducted periodically to assess the response to leprosy treatment. The primary end points were effec-

Skin thermography

tiveness of the method under different boundary conditions over the period, and rapid assessment of the

Indeterminate leprosy

response to leprosy treatment. The patient achieved sustained hepatitis C virological response 6 monthsafter the end of the treatment. The normalized infrared results demonstrate the leprosy treatment suc-cess in spite of the concurrent hepatitis C treatment, since day 87, whereas repigmentation was visuallyassessed only after day 182, and corroborated with a skin biopsy on day 390. The method detected theeffectiveness of the leprosy treatment in 87 days, whereas repigmentation started only in 182 days. Hep-atitis C and leprosy treatment did not affect each other.

Ó 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

consists of the average skin temperature at the affected re-gion ± the standard deviation of the measurements [13], (ii) a com-

According to Wallace [1], medical thermography was conceived

pound thermographic index (CTI) in correlation with low density

and first applied to patients by Lawson [2] in Montreal, and

lymphocytes (LDL) [14,15], (iii) a normalized thermographic index

reported on two patients with breast cancers, showing increased

(DTn), which consists of the evaluation of the TI at the affected re-

temperature over the tumor site. Williams et al. [3,4] reported on

gion minus the TI of a normal selected region [16], and (iv) a ds in-

an infrared survey of 200 cases of breast cancer, also detecting

dex (difference between temperatures of tissues of a breast tumor

increased temperature on the affected skin regions. These studies

and normal tissues) [17]. Inoue et al. [18] evaluated patients with

might be considered the starting points of medical infrared

rheumatoid arthritis after 20 min of thermal stabilization in a room

thermal imaging.

at 20 °C showing that the HDI results correlated better with clinical

In an attempt to provide objective means to analyze skin sur-

observations than the TI.

face temperature readings, Collins et al. [5–7] developed the ther-

An alternative to medical infrared imaging is the so called skin-

mographic index to quantify infrared thermal imaging. The method

contact thermography. Recently, a wearable device for skin-con-

was then utilized in several studies with different disorders [8–12].

tact thermography using silicon sensors was studied by Giansanti

All studies showed the effect of medications on the thermographic

[19], who designed a cubic–spline interpolation procedure to im-

index, which returned to basal levels with the symptoms remis-

prove the spatial resolution of the device. The methodology does

sion. In general, the results established the concept of a stable envi-

not compare to infrared imaging in terms of spatial resolution,

ronment as one of a number of essentials to reliable technique.

but it is required when subjects need to be monitored for 24 h,

Other methods for medical infrared imaging quantification have

since the infrared camera cannot be affixed to a body segment or

been proposed, such as: (i) a heat distribution index (HDI), which

to a breast for 24 h.

The previously proposed methods for medical thermography

(TI, HDI, CTI, DTn, ds, and skin-contact thermography) measure lo-cal temperatures that are significantly affected by ambient temper-

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +55 41 3361 3307; fax: +55 41 3361 3129.

ature and patient metabolism. A way to normalize temperature

E-mail address: [email protected] (J.V.C. Vargas).

1350-4495/$ - see front matter Ó 2008 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.infrared.2008.11.003

Author's personal copy

J.V.C. Vargas et al. / Infrared Physics & Technology 52 (2009) 42–47

area of the affected region, m2

thermographic index, °C

compound thermographic index, °C

central body temperature, °C

difference between temperatures of tissues of a breast

ambient temperature, °C

tumor and normal tissues, °C

cartesian coordinates, m

heat distribution index, °C

low density lymphocytes

multidrug therapy

normalized thermographic index, °C

rifampin, ofloxacin, and minocycline single dose inde-

dimensionless temperature, Eq. (2)

terminate leprosy treatment

average dimensionless temperature, Eq. (4)

affected region domain, Fig. 1

skin surface temperature at a point, °C

readings for any specific location would therefore be of much use

in medical practice. Normalized infrared imaging could provide

means for early and accurate detection of the response to treat-

The dimensionless temperature defined by Eq. (1) is expected to

ment, mainly when other treatments are conducted simulta-

deliver normalized temperature readings, independently of mea-

neously due to co-infections. The literature reports a relatively

suring units, for any particular skin location, whatever body and

high prevalence of hepatitis C combined with leprosy in several

ambient temperatures are registered. The dimensionless tempera-

countries [20,21], but, within the knowledge of the authors, does

ture, as defined by Eq. (1), was first introduced in engineering by

not document the resulting effect of combined peginterferon

Pohlhausen [23], who used it to present the normalized tempera-

alfa-2a and ribavirin on leprosy patients undertaking concurrent

ture profile solution to the thermal boundary layer problem of lam-

multidrug therapy (MDT) and vice versa.

inar forced convection on a flat plate.

In addition to the definition of a local measuring quantity, it is

1.1. Objectives of the paper

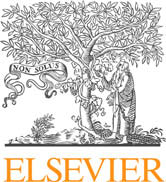

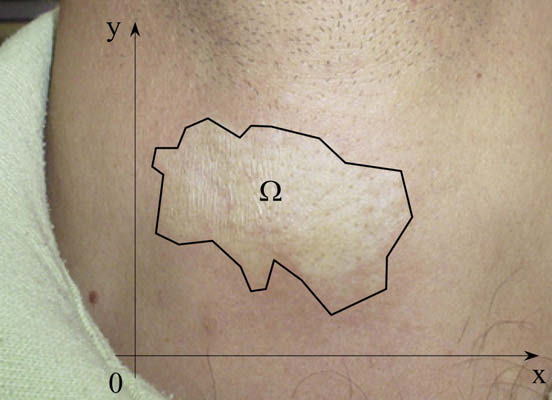

necessary to specify a representative quantity for the skin regionof interest, namely, the affected region. Fig. 1 shows a portion of

Two objectives were sought in this work: (i) to suggest a nor-

the affected skin, in which a polygonal line defines a domain X

malized methodology for general thermography interpretation,

with respect to two Cartesian axes x and y. The polygonal line

and (ii) to test the methodology in the treatment follow-up of an

should be appropriately specified to encompass the entire region

indeterminate leprosy and hepatitis C case, for early and accurate

of interest. Each region provides a dimensionless temperature field,

detection of leprosy skin lesion evolution.

which depends on x and y, i.e., h(x, y). Using the mean value theo-rem for integrals, the average dimensionless temperature for the

2. Materials and methods

entire region of interest is therefore evaluated by:

The methodological flow was divided in three steps:

� The development of the theoretical methodology for normalized

Eq. (2) defines the quantity to be obtained through the infrared

infrared imaging.

camera temperature readings in the entire selected region of inter-

� The experimental procedure for temperature data acquisition

est, and through the measured central body and ambient

and calculation of uncertainties, and

� The performance evaluation of the suggested normalized infra-

red imaging methodology with a case study of concurrent hep-

2.2. Temperature measurements

atitis C and indeterminate leprosy.

The infrared images were obtained using a SAT-S160 Infrared

camera, manufactured by SAT (Guangxhou SAT Infrared Technol-

The energy conservation principle [22] states that, for any time

interval, the variation of the energy of a system results from the ex-change of matter and energy with the exterior, and the system en-ergy variation is equal and opposite to the external world energyvariation. Considering the system as a portion of an individual skin(the region of interest), its energy variation is a result of the ex-change of matter and energy with the ambient and the rest ofthe individual's body. Therefore, since energy is directly relatedto temperature, a general methodology to interpret the tempera-ture readings obtained from an individual skin should considerthe local environmental conditions and the individual metabolism.

An appropriate dimensionless variable was identified to inter-

pret the infrared camera temperature readings. The variable is awell known dimensionless temperature in engineering heat trans-fer, and combines the locally measured temperature with the cen-tral body and ambient temperatures, as follows:

Fig. 1. The skin region of interest, namely, the affected region.

Author's personal copy

J.V.C. Vargas et al. / Infrared Physics & Technology 52 (2009) 42–47

ogy CO., LTD), with a spatial resolution of 2.2 mrad, 160 � 120 pix-

simultaneously and directly calculate the region of interest average

els, a bias limit of ±2% (temperature accuracy), and a temperature

resolution of 0.1 °C. The camera was placed at a horizontal distance

Before the beginning of the experiments, several tests were per-

of 1 m away from the region of interest on the patient's skin in or-

formed with three different ambient temperatures in an environ-

der to ensure the same view factor and dimensions for the selected

mentally controlled laboratory, i.e., T1 = 15.5, 20 and 26 °C. The

region of interest in all thermographs. Although the literature

tests consisted of, for the same individual, to perform the data

shows discrepancies for the values of human skin emissivity, it

acquisition of the temperature field on the selected region of inter-

was possible to attribute an emissivity of 0.975 to the human skin

est and body temperature. Then, the value of �

h was computed for

surface based on relatively recent work [24–26].

these three different conditions, resulting in approximately equal

The average of the measurements taken with four high preci-

h for all cases. Uncertainties were computed based on

sion thermistors of type YSI44004 (YSI Inc., USA), standard type

these three values, taken as the precision limit of the temperature

Bead I, with a maximum diameter of 2.4 mm, was utilized to esti-

measurements (two times the standard deviation [28]), since the

mate the ambient temperature close to the patient in the testing

temperature bias limit (±2% of the actually measured temperature

room, T1. A fifth and a sixth thermistor were placed under the

with the infrared camera and ±0.001 °C with the thermistors) was

two armpits of the individual being tested, and the average of

considered negligible in presence of the temperature precision lim-

the measurements was used to estimate the patient's central body

it (at least one order of magnitude smaller). In this way it was dem-

temperature, Tb ± 0.001 °C. All tests started at least ten minutes

onstrated that the dimensionless group really normalizes the

after the body temperature thermistors were placed, in order to

results, making them independent of the ambient and body tem-

read the actual body temperature of the subject.

perature conditions. For the sake of accuracy, in the present study,

The thermistors were immersed in a constant temperature bath,

the tests were all performed within the ambient temperature

and sixty-four temperature measurements were made at 20 °C,

range mentioned above, i.e., 15.5 °C 6 T1 6 26 °C.

30 °C, 40 °C, . . , 80 °C. The largest standard deviation of these mea-surements was 0.0006 °C, therefore the bias limit was considered

±0.001 °C for all the thermistors.

The experimental work involved the acquisition of temperature

A 50 year-old man was referred to an outpatient clinic for treat-

data in real time. This task was performed through the utilization

ment of a single lesion with the approximate shape of an ellipse

of a computational data acquisition system which consisted of a

(major axis: 6 cm, minor axis: 4 cm) in the cervical region, as

digital multimeter board, NI PCI-4060, a NI PCI-6703 analog output

shown in Fig. 1. Microscopy was conducted on a rectified lamellar

board, a SCXI-1127 32-channel high voltage multiplexer, and

and epidermis corneal layer, with preserved thickness, measuring

accessories, all manufactured by National Instruments, USA, which

0.3 � 0.3 � 0.3 cm, collected from the affected region. The superfi-

allows for the sequential data acquisition from 32 channels at

cial and deep dermis presented moderate lymphocyte inflamma-

interval times of 0.1 s. All the data were processed by a home made

tory infiltrate, with plasmocytes, predominantly perivascular and

Labview application (National Instruments, USA) to convert the

perineural, sometimes interstitial, with the presence of one acid-

sensors signals in readable temperatures. In this way, the temper-

fast bacillus. Therefore the patient was diagnosed with indetermi-

ature measurements originated from the six thermistors utilized in

nate leprosy. Because of his past history of an untreated chronic

the experiments were read almost simultaneously, i.e., in less than

hepatitis C and evidence of elevated liver enzymes and positive

a second. The program also generated files with the numerical data

qualitative HCV–RNA (Cobas Amplicor Hepatitis C Virus Test, ver-

measured for the patient, and allowed the calculation of the aver-

sion 2.0, Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, NJ, USA), a liver

age dimensionless temperature according to Eq. (2), with the re-

biopsy was performed before starting leprosy treatment. The liver

gion of interest temperature field data obtained with the infrared

specimens showed moderate necroinflammatory activity and ad-

camera and a bi-dimensional numerical integration procedure

vanced fibrosis (METAVIR stage F3). HCV genotyping was deter-

(Simpson's rule [27]). With the equipment described in this sec-

mined as 3a (Inno LipA HCV II, Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium).

tion, it was possible to measure all required temperatures almost

The patient was then monitored for 587 days after receiving a

single dose of 600 mg of rifampin, 400 mg of ofloxacin, and100 mg of minocycline, i.e., the so called ROM treatment for inde-

terminate leprosy. Thirty days later, he started the current stan-dard therapy for hepatitis C [29,30], with 180 lg peginterferon

alfa-2a by subcutaneous injection once a week, plus 1000 mg oralribavirin daily for 24 weeks, achieving sustained virological re-

sponse 6 months after the end of the treatment, and thereafter

(negative quantitative HCV–RNA). Blood tests were utilized to fol-low the response to the hepatitis C treatment, and both visual and

normalized infrared imaging were conducted periodically (0, 15,28, 46, 59, 73, 87, 144, 182, 204, 257, 367 and 587 days) to assess

the response to leprosy treatment. On day 390, a biopsy was con-

ducted on a punch of pink–red skin tissue extracted from thescarred repigmented area, which was soft and elastic, measuring

0.3 � 0.3 � 0.3 cm, showing that the epidermis had no particulari-ties, and that in the mid and deep dermis there was disorganiza-

tion of thickened collagen groups, with the Ziehl–Neelsen

staining method showing no evidence of acid-fast bacilli. The pri-mary end points were the effectiveness of the normalized temper-

Fig. 2. The patient's response to hepatitis C treatment in time through blood tests:

ature readings under different boundary conditions over the test

—h— Fastingglucose [�102 mg/dl];

period, and the rapid assessment of the response to the leprosy

Platelet count [�1011/l];

Erythrocyte count

treatment through normalized infrared imaging, while undergoing

Hematocrit [�10];

Leucocyte count [�109/l];

Absolute neutrophil count [�109/l].

simultaneous hepatitis C treatment.

Author's personal copy

J.V.C. Vargas et al. / Infrared Physics & Technology 52 (2009) 42–47

hot and cold spots, or asymmetries; (ii) static images on occasionsseparated by substantial length of time to monitor disease progress

A recent study [31] still points out the need for an environmen-

or treatment or to detect and estimate the severity of inflamma-

tally controlled laboratory and a protocol to ensure consistency for

tion, and (iii) series of images over a period of minutes to monitor

comparing infrared images captured on different occasions (e.g.,

the recovery of skin temperature following a provocation such as

patient thermal equilibration with the ambient, absence of skin

thermal, mechanical, or chemical stress. The proposed normalized

creams). The protocol recommends the thermal equilibration of a

methodology has the potential to simplify and give more objectiv-

patient at a temperature too high for vasoconstriction to occur,

ity to infrared imaging protocols in all modes, thus improving the

but low enough not to mask the effects of inflammation or angio-

accuracy of image medical interpretation.

genesis, which adds a considerable deal of subjectivity to the exam,

The experimental results are shown in Figs. 2–4. The experi-

since no specific temperature levels are established. In time, pro-

mentally measured points were interpolated with cubic–splines,

gress has been made on producing open systems [32,33] for cap-

for a better visualization of the physical phenomena. The results

are organized in a logical sequence, i.e.: (i) regular blood tests to

thermal images relating a patient, suggesting three modes of image

assess the response to hepatitis C treatment; (ii) the physical and

treatment: (i) single static image at an instant in time to identify

infrared images comparison of the monitored leprosy skin lesion,

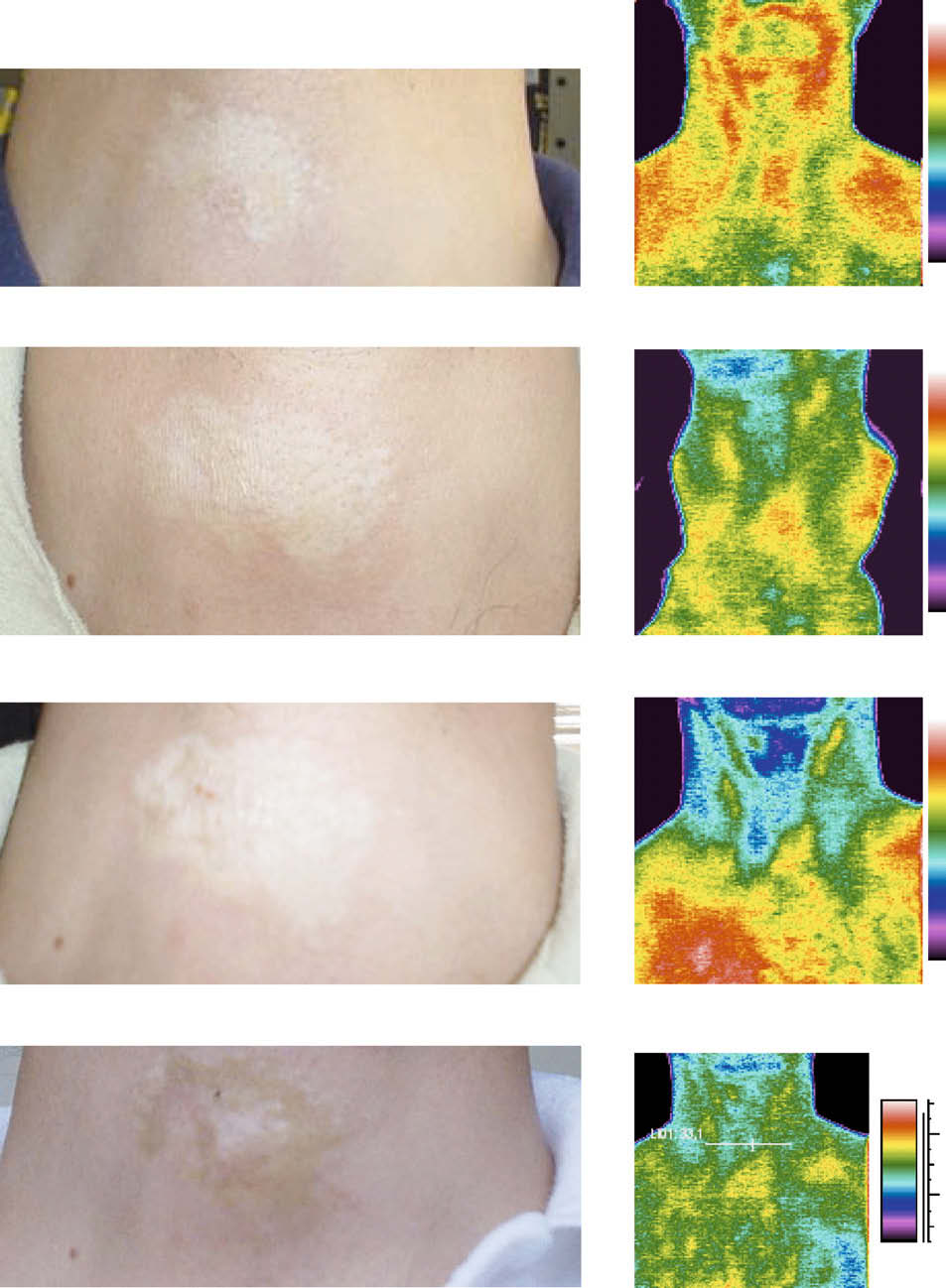

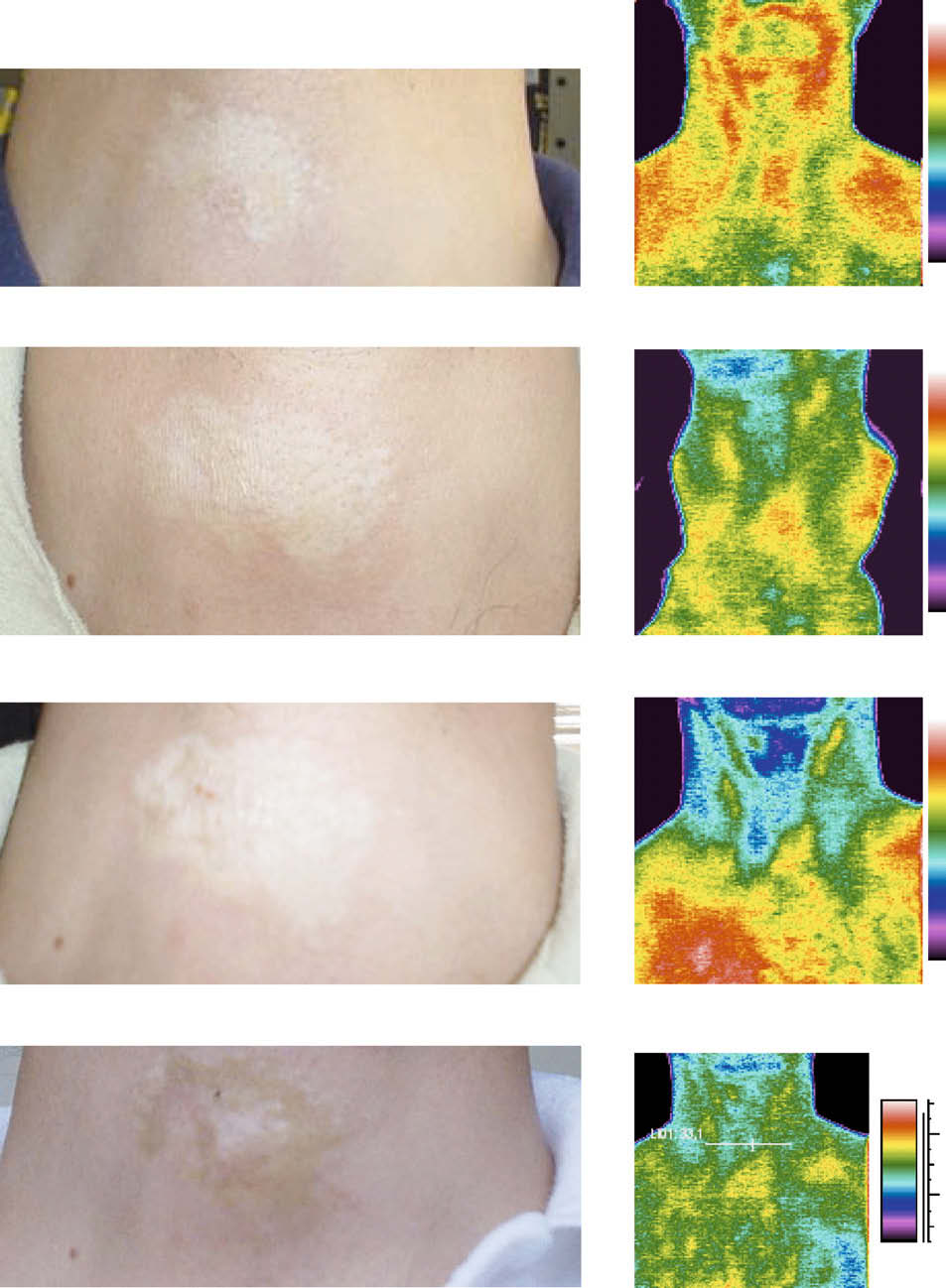

Fig. 3. The correspondence between actual photos and infrared images of the leprosy skin lesion captured on different occasions during treatment follow-up. From top tobottom: day 0, day 59, day 87, and day 257.

Author's personal copy

J.V.C. Vargas et al. / Infrared Physics & Technology 52 (2009) 42–47

the same value ð�h � 2%Þ on the day the image was taken, showingthat the value was indeed normalized in the range of tested ambi-ent temperatures. The procedure was repeated in different occa-sions (0, 15, 28, 46, 59, 73, 87, 144, 182, 204, 257, 367 and 587

days). The 2% uncertainty was the highest value obtained in allmeasurements, therefore it was the value used to compute the er-ror bars shown in Fig. 4, where the results are shown graphically. It

is observed clearly that after the single dose of the leprosy ROMtreatment the average dimensionless temperature started to drop,stabilizing at a lower level after day 87, approximately, and

remaining at that plateau until the end of the observation period.

The normalized infrared results therefore demonstrate the favor-able leprosy treatment outcome in spite of the concurrent hepatitisC treatment, since day 87, whereas repigmentation was visually as-

sessed only after day 182, and corroborated with a skin biopsy on

day 390. Since the hepatitis C treatment causes a significant drop

in leucocyte and absolute neutrophil count, it was not obvious

Fig. 4. The patient's average dimensionless temperature response at the skin

whether or not the leprosy treatment outcome would be affected

affected region in time.

by that. Although more concurrent leprosy and hepatitis C casesneed to be studied, in the absence of other documented cases,the single case herein studied represents a first assessment that

and (iii) the skin lesion average dimensionless temperature in

hepatitis C and indeterminate leprosy treatments did not affect

Fig. 2 presents a selection of the most representative blood tests

monitored during the hepatitis C treatment and the remaining per-iod of observation. Abnormal liver enzyme levels (AST and ALAT)

4. Discussion and conclusions

were present in the beginning of the hepatitis C treatment (day30), which dropped initially, elevated again (day 100), later show-

In this study, it was proposed and investigated the utilization of

ing a trend to normal ranges (day 180), i.e., the treatment end

an average dimensionless temperature for infrared imaging analy-

point, and indeed stabilizing at normal levels afterwards. Other

sis. For that, the methodology was theoretically presented and ap-

tests (platelet, erythrocyte, hematocrit, leucocyte, and absolute

plied to one case study of indeterminate leprosy and hepatitis C.

neutrophil) showed substantial drop during treatment, and stabi-

The bulk of the experimental results showed that normalized infra-

lizing at normal levels after the end of the treatment. Those results,

red imaging was able to detect the effectiveness of the leprosy

together with the negative quantitative HCV–RNA demonstrate the

treatment in 87 days, in spite of variable environmental conditions,

hepatitis C treatment success in spite of concurrent leprosy

whereas repigmentation started visually only in 182 days. Com-

bined peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin did not affect the patient

Actual photos and infrared images are shown in Fig. 3. The

response to indeterminate leprosy treatment and vice versa. How-

infrared images were obtained with the ambient temperature at

ever, for a better assessment of the effects of the leprosy and hep-

20 °C, and the central body temperature was 36.5 °C in all occa-

atitis C medications on each other, a larger sample of patients

sions to ensure consistency for comparing images captured on dif-

being treated simultaneously for both conditions should be

ferent days. Four occasions were selected to compare the direct

visual and infrared image assessments of the region of interest.

The key conclusion is that with a normalized methodology,

On day 0, i.e., when the ROM single dose was taken by the patient,

there is potential for production of analysis criteria for high resolu-

an elevated temperature distribution was observed on the skin le-

tion infrared imaging temperature readings for the diagnosis and

sion, in comparison with the cervical region around it. Since there

follow-up of skin lesions in leprosy treatment, independently of

is immunocytochemical evidence that the initial damage in leprosy

central body and local environmental temperatures, and possibly

is directed at distal, small, unmyelinated nerve fibers, peripheral

to all other skin-detectable pathologies, with no need for an envi-

autonomic dysfunction is expected, resulting in local hyperemia

ronmentally controlled laboratory and complex protocols.

and elevated skin temperature [34]. On day 15, it was seen quali-tatively that the temperature distribution on the region of interest

dropped to lower values, closer to the surrounding normal skin val-ues, but the lesion remained pale. On day 87, the infrared image

Additional research has been planned to show the effectiveness

shows even lower values than the previous ones, but no lesion

of the normalized thermography methodology for diagnosis and

repigmentation was observed. On day 257, the temperature distri-

follow-up of all forms of leprosy and possibly other skin-detectable

bution was very similar to the previous one, and repigmentation

pathologies, and to produce comprehensive dimensionless temper-

was also in progress. In sum, although a stabilized and fairly uni-

ature analysis criteria for them.

form temperature distribution was observed from day 87, the skinlesion did not show signs of repigmentation until day 182, which

Conflicts of interest statement

was the day when the skin repigmentation process was detectedin the laboratory (not shown in Fig. 3).

We declare that we have no conflict of interests.

Although Fig. 3 documented the decrease in temperature values

in the region of interest qualitatively, it would be more instructive

for clear medical interpretation if precise quantitative informationwere available. For that, the region of interest average dimension-

The authors acknowledge with gratitude the support of the Bra-

less temperature was calculated at 3 different ambient tempera-

zilian National Council of Scientific and Technological Develop-

ture levels, i.e., T

1 = 15.5,20 and 26 °C, obtaining approximately

Author's personal copy

J.V.C. Vargas et al. / Infrared Physics & Technology 52 (2009) 42–47

[18] K. Inoue, J. Nishioka, T. Kobori, Y. Nakatani, S. Hukuda, The use of

thermographic index and the heat distribution index, Ryumachi 30 (5)

[1] J.D. Wallace, C.M. Cade, Clinical Thermography, CRC, Cleveland, OH, 1975.

(1990) 356–361.

[2] R.N. Lawson, Implications of surface temperatures in the diagnosis of breast

[19] D. Giansanti, Improving spatial resolution in skin-contact thermography:

cancer, Can. Med. Assoc. J. 75 (1956) 309–315.

comparison between a spline based and linear interpolation, Med. Eng. Phys.

[3] K.L. Williams, F.L. Williams, R.S. Handley, Infrared radiation thermometry in

30 (2008) 733–738.

clinical practice, Lancet 2 (OCT29) (1960) 958–959.

[20] H. Rosa, R. Martins, B. Vanderborght, Short report: association between leprosy

[4] K.L. Williams, R.S. Handley, F.L. Williams, F. Infrared thermometry in the

and hepatitis C infection: a survey in a region of central Brazil, Am. J. Trop.

diagnosis of breast disease, Lancet 2 (721) (1961) 1378–1379.

Med. Hyg. 55 (1) (1996) 22–23.

[5] A.J. Collins, E.F.J. Ring, J.A. Cosh, P.A. Bacon, Quantitation of thermography in

[21] A.C.M. Braga, I.J.M. Reason, E.C.P. Maluf, E.R. Vieira, Leprosy and confinement

arthritis using multi-isothermal analysis. I. The thermographic index, Ann.

due to leprosy show high association with hepatitis C in southern Brazil, Acta

Rheum. Dis. 33 (2) (1974) 113–115.

Tropica 97 (2006) 88–93.

[6] E.F.J. Ring, A.J. Collins, P.A. Bacon, J.A. Cosh, Quantitation of thermography in

[22] I. Prigogine, D. Kondepudi, Thermodynamique, Éditions Odile Jacob, 1999. ch.

arthritis using multi-isothermal analysis. II. Effect of nonsteroidal anti-

inflammatory therapy on the thermographic index, Ann. Rheum. Dis. 33 (4)

(1974) 353–356.

flüssigkeiten mit kleiner reibung und kleiner wärmeleitung, Z. Angew Math.

[7] A.J. Collins, Anti-inflammatory drug assessment by the thermographic index,

Mech. 1 (1921) 115–121.

Acta Thermographica 1 (2) (1976) 73–79.

[24] J. Steketee, Spectral emissivity of skin and pericardium, Phys. Med. Biol. 18 (5)

[8] E.F.J. Ring, Thermographic evaluation of calcitonin therapy in Paget's disease of

(1973) 686–694.

the tibia, Acta Thermographica 1 (2) (1976) 67–72.

[25] T. Togawa, Non-contact skin emissivity: measurement from reflectance using

[9] E.F.J. Ring, Computerised thermography for osteo-articular diseases, Acta

step change in ambient radiation temperature, Clin. Phys. Physiol. Meas 10 (1)

Thermographica 1 (3) (1976) 166–172.

(1989) 39–48.

[10] E.F.J. Ring, P.A. Bacon, Quantitative thermographic assessment of inositol

[26] B.F. Jones, A re-appraisal of the use of infrared thermal image analysis in

nicotinate therapy in Raynaud's phenomena, J. Int. Med. Res. 5 (4) (1977) 217–

medicine, IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 17 (6) (1998) 1019–1027.

[27] D. Kincaid, Cheney, Numerical Analysis Mathematics of Scientific Computing,

Springer, Berlin, 1991.

corticosteroid injection in rheumatoid arthritis, Ann. Rheum. Dis. 40 (2)

[28] Editorial. Journal of heat transfer policy on reporting uncertainties in

(1981) 132–135.

experimental measurements and results, ASME J. Heat Transfer 115 (1993)

[12] S. Zieniuk, B. Stawarz, K. Zieniuk, Infra-red thermography testicular studies of

patients with short spermatic cords and quality of sperm morphology,

[29] D.B. Strader, T. Wright, D.L. Thomas, L.B. Seef, Diagnosis, management and

Ginekol. Pol. 69 (6) (1998) 551–554.

treatment of hepatitis C, Hepatology 39 (4) (2004) 1147–1171.

[13] R.S. Salisbury, G. Parr, M. De Silva, B.L. Hazleman, D.P. Page-Thomas, Heat

[30] J.L. Dienstag, J.G. McHutchison, American gastroenterological association

distribution over normal and abnormal joints: thermal pattern and

technical review on the management of hepatitis C, Gastroenterology 130

quantification, Ann. Rheum. Dis. 42 (5) (1983) 494–499.

(1) (2006) 231–264.

[14] G.M. Papadimitriou, P.A. Bacon, N.D. Hall, Circulating activated lymphocytes in

[31] B.F. Jones, P. Plassmann, Digital infrared thermal imaging of human skin, IEEE

rheumatoid arthritis: a marker of synovial inflammation, J. Rheumatol. 9 (2)

Eng. Med. Biol. 21 (6) (2002) 41–48.

(1982) 217–223.

[32] P. Plassmann, E.F.J. Ring, An open system for the acquisition and evaluation of

[15] G.J. Alexander, P.A. Bacon, F. Cavalcanti, D.R. Blake, N.D. Hall, Low density

medical thermological images, Eur. J. Thermol. 7 (4) (1997) 216–220.

lymphocytes: their relationship to disease activity and to antirheumatic

[33] E.F.J. Ring, The historical development of temperature measurement in

therapy, Br. J. Rheumatol. 23 (1) (1984) 6–14.

medicine, Infrared Phys. Technol. 49 (2007) 297–301.

[16] H. Warashina, Y. Hasegawa, H. Tsuchiya, S. Kitamura, K. Yamauchi, Y. Tori, M.

[34] A.F. Hoeksma, W.R. Faber, Assessment of skin temperature by palpation in

Kawasaki, S. Sakano, Clinical, radiographic, and thermographic assessment of

leprosy patients: interobserver reliability and correlation with infrared

osteoarthritis in the knee joints, Ann. Rheum. Dis. 61 (9) (2002) 852–854.

thermometry, Int. J. Lepr. Other Mycobact. Dis. 68 (1) (2000) 65–67.

[17] T. Yahara, T. Koga, S. Yoshida, S. Nakagawa, H. Deguchi, K. Shirouzu,

Relationship between microvessel density and thermographic hot areas inbreast cancer, Surg. Today 33 (4) (2003) 243–248.

Source: http://www.thermografie-centrum.nl/forms/m_infrared_physics_and_technology.pdf

Final Report: The Recovery Partnership Review of Alcohol Treatment Services Mike Ward, Mark Holmes, Lauren Booker Executive summary 2. Four key findings 3. The current state of the alcohol treatment system 4. Other parts of the care pathway 5. The impact of the recovery agenda, peer support, and mutual aid 6. The commissioning process 7. The role of non-specialist services

LE TOUR DES ANNAPURNAS LE TOUR DES ANNAPURNAS Népal - NP Considéré comme l'un des plus beaux treks du monde, ce voyage n'est pas devenu célèbre par hasard. Des raisons objectives, comme l'exceptionnelle variété des paysages rencontrés, ont largement contribué à sa renommée. Lors de cette découverte pédestre d'une ampleur himalayenne, vos pas vous mènent en quelques jours des bananiers aux neiges éternelles, après la traversée de rizières, de forêts de pins ou de rhododendrons, de déserts de roche et de sable. De 900 à 5 400 mètres, un monde de cultures variées défile devant vos yeux émerveillés : villages gurungs ou thakalis éparpillés dans les champs en terrasses, petits villages tibétains serrés autour de leur monastère… Un somptueux périple dans le pays des rizières, hindouiste, et dans les hautes vallées d'influence bouddhiste et tibétaine très marquée. Ces dix jours de marche sont agrémentés par la grâce et la gentillesse des Népalais, toujours chaleureux. Le voyage se termine à Jomosom, en haut des gorges de la Kali Gandaki. Un vol somptueux nous attend entre les massifs du Dhaulagiri et des Annapurnas.