Cincinnati.vc.ons.org

This material is protected by U.S. copyright law. Unauthorized reproduction is prohibited. To purchase quantity reprints,

please e-mail

[email protected] or to request permission to reproduce multiple copies, please e-mail

[email protected].

An Interdisciplinary Consensus on Managing

Skin Reactions Associated With Human

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors

Beth Eaby, MSN, CRNP, OCN®, Ann Culkin, RN, OCN®, and Mario E. Lacouture, MD

The use of human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER1/EGFR) inhibitors, such as erlotinib, cetuximab, and panitumumab, often is accompanied by the development of a characteristic spectrum of skin toxicities. Although these toxicities rarely are life threatening, they can cause physical and emotional distress for patients and caregivers. As a result, practitioners often withdraw the drug, potentially depriving patients of a beneficial clinical outcome. These reactions do not necessarily require any alteration in HER1/EGFR-inhibitor treatment and often are best addressed through symptomatic treatment. Although the evidence for using such therapies is limited, an interdisciplinary HER1/EGFR-inhibitor dermatologic toxicity forum was held in October 2006 to discuss the underlying mechanisms of these toxicities and evaluate commonly used therapeutic interventions. The result was a proposal for a simple, three-tiered grading system for skin toxicities related to HER1/EGFR inhibitors to be used in therapeutic decision making and as a framework for building a stepwise approach to intervention.

At a Glance

e use of human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER1/

The use of HER1/EGFR-targeted therapies, such as erlo-

tinib (Tarceva®, OSI Pharmaceuticals, Inc.), cetuximab (Erbitux®, Bristol-Myers Squibb), and panitumumab (VectibixTM, Amgen Inc.), often is accompanied by

EGFR) inhibitors often is accompanied by the development

the development of a characteristic spectrum of skin

of a characteristic class-specific spectrum of skin toxicities.

toxicities (Rhee, Oishi, Garey, & Kim, 2005). Although these

in toxicities related to HER1/EGFR inhibitors do not necessar-

events rarely are life threatening, they can cause physical and

ily require alteration in HER1/EGFR-inhibitor treatment and of-

emotional distress for patients and caregivers. Often, the rash

ten are addressed best through symptomatic management.

may be mistaken as an uncontrollable adverse effect rather than a treatable side effect. As a result, practitioners withdraw the drug,

idence-based treatment recommendations for skin tox-

potentially depriving patients of a beneficial clinical outcome.

icities related to HER1/EGFR inhibitors are not available

Oncology nurses often are the first point of contact for patients

because no data from control ed clinical studies have been

who are receiving treatment; therefore, understanding the clinical

basis for such skin reactions and offering effective and appropriate assessments and interventions are critical.

On October 29, 2006, an interdisciplinary forum was held in

Beth Eaby, MSN, CRNP, OCN®, is a nurse practitioner at the University of

Chicago, IL, to discuss skin toxicities associated with HER1/EGFR-

Pennsylvania in Philadelphia; Ann Culkin, RN, OCN®, is a clinical nurse at

targeted therapies. Oncologists, dermatologists, pharmacists, and

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, NY; and Mario E.

nurses shared their knowledge on the underlying mechanisms

Lacouture, MD, is a dermatologist in the Department of Dermatology at

of these events and evaluated existing practices in the hope of

SERIES Clinic and the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center at

reaching a consensus strategy on how best to manage them. This

Northwestern University in Chicago, IL. Eaby is a member of the Tarceva®

article provides an overview of their discussions.

speakers bureau and Culkin is a member of the Advisory Board and speak-ers bureau, both for Genentech. Lacouture received an honorarium from Genentech and is a speaker for Genentech, ImClone, and OSI Pharmaceu-

Human Epidermal Growth Factor

ticals. Mention of specific products and opinions related to those products do not indicate or imply endosement by the

Clinical Journal of Oncology

Nursing or the Oncology Nursing Society. (Submitted July 2007. Accepted

As a result of an increased understanding of the underly-

for publication September 1, 2007.)

ing molecular causes of cancer, biologic targeted agents have

Digital Object Identifier:10.1188/08.CJON.283-290

Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing • Volume 12, Number 2 • Managing Skin Reactions

emerged since the mid-1990s as a new strategy in the treat-

tyrosine kinase (Yarden & Sliwkowski, 2001). Both prevent

ment of various malignancies. These targeted agents interact

the initiation of cell-signaling pathways that normally promote

with specific molecules that are pivotal in tumor growth and

tumor-cell proliferation, migration, adhesion and angiogenesis,

development. Traditional "cytotoxic" chemotherapies not

and inhibit apoptosis (Arteaga, 2001). A fourth agent, the TKI

only kill tumor cells by affecting processes that commonly are

gefitinib (Iressa®, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals), initially was

overactive or enhanced in cancerous tissue but also may be

approved in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

important in affecting normal cells. Targeted agents can exert

for third-line use, based on the results of a randomized phase II

their influence by, among other things, inhibiting tumor-cell

trial (Kris et al., 2003). However, data from a phase III confir-

proliferation, inducing programmed cell death, inhibiting

matory trial failed to show a survival benefit and its use now is

angiogenesis, and enhancing antitumor immune responses

restricted to patients currently or previously benefiting from it

(Hoang & Schiller, 2002). Common targets for these agents

or to patients enrolled in a clinical study (FDA, 2005).

include growth factors such as the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF); intracellular signaling molecules, including

Skin Reactions Associated

cyclooxygenase-2 and the BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase; and cell-surface receptors (e.g., members of the HER family, which

With Human Epidermal Growth Factor

includes HER1/EGFR).

The HER1/EGFR is an attractive target for new biologic

targeted agents because it has been implicated in the develop-

Largely because of their specificity of action, biologic targeted

ment of a range of tumor types (Greatens et al., 1998; Ohsaki

agents often are considered to have a more favorable toxic-

et al., 2000; Salomon, Brandt, Ciardiello, & Normanno, 1995).

ity profile than traditional chemotherapy. This also is true for

Overexpression of the receptor also has been correlated with

HER1/EGFR-targeted therapies, which generally are associated

disease progression, poor prognosis, and a reduced sensitivity

with fewer hematologic adverse events than chemotherapy.

to chemotherapy (Cooke, Reeves, Lannigan, & Stanton, 2001;

However, patients treated with HER1/EGFR-targeted therapies

Nicholson, Gee, & Harper, 2001). Several HER1/EGFR inhibitors

often do present with a unique group of skin reactions (Rhee et

are in clinical development, and three (erlotinib, cetuximab,

al., 2005), which occur in more than 50% of patients receiving

and panitumumab) have demonstrated efficacy in a range of

these treatments (Segaert & Van Cutsem, 2005).

indications and received U.S. Food and Drug Administration

Clinical trials with HER1/EGFR-targeted inhibitors have

(FDA) approval. Erlotinib is an oral, reversible, tyrosine kinase

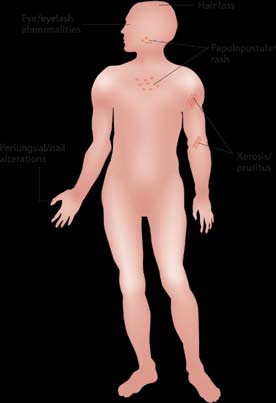

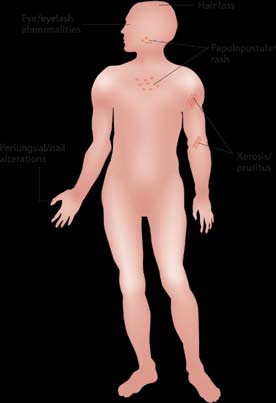

revealed a spectrum of skin toxicities of varying severity (see

inhibitor (TKI), whereas cetuximab and panitumumab are IV

Table 1 and Figure 1). The most commonly reported reactions

administered anti-HER1/EGFR monoclonal antibodies (MAbs).

are mild-to-moderate skin rashes that occur most frequently

MAbs prevent ligands, such as the EGF, from binding to the

on the face and upper trunk. Other common dermatologic

receptor, whereas TKIs block the activity of the receptor's

reactions include xerosis (dry skin), pruritus, nail changes

Table 1. Spectrum of Dermatologic Reactions Associated With Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

Inhibitors

TImE couRSE

Monomorphous erythematous maculopapular, follicular,

Onset: one to three weeks of treatment;

or pustular lesions, which may be associated with mild

maximum: three to five weeks of treatment;

resolution: within four weeks of treatment

cessation but may wax and wane

Paronychia and fissuring

Painful periungual granulation-type or friable pyogenic

Onset: after two to four months of treat-

granuloma-like changes associated with erythema,

ment; resolution: persistent, several months

swelling and fissuring of lateral nailfolds, and/or distal

Curlier, finer, and more brittle hair on scalp and extremi-

Variable onset: after 7–10 weeks to many

ties; also extensive growth and curling of eyelashes and

Diffuse fine scaling

Occurs after appearance of rash

Flushing, urticaria, and anaphylaxis

Occurs on the first day of initial dosing

Mild to moderate mucositis, stomatitis, aphthous ulcers

Onset during treatment, not related to dose or

schedule; resolution without specific measures

Note. From "Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitor–Associated Cutaneous Toxicities: An Evolving Paradigm in Clinical Management," by T.J. Lynch, Jr., E.S. Kim, B. Eaby, J. Garey, D.P. West, and M.E. Lacouture, 2007,

Oncologist, 12(5), p. 614. Copyright 2007 by AlphaMed Press. Reprinted with permission.

April 2008 • Volume 12, Number 2 • Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing

The severity of rash also appears to vary between agents. In

general, rash associated with the use of anti-HER1/EGFR MAbs tends to be more severe than that observed with TKIs, present-ing as a more purulent and pustular reaction, which may require more aggressive interventions (Sipples, 2006).

The different modes of administration for these agents might

be one reason: TKIs (e.g., erlotinib, gefitinib) are administered orally on a daily basis, whereas MAbs (e.g., cetuximab, panit-mumumab) are given intravenously once a week or every two weeks. The pharmacokinetic properties of these agents are therefore different, with potentially greater differences in peak and trough concentrations for MAbs than for TKIs. This may ex-plain the differing incidence and manifestation of rash observed

To view this image,

with these agents, particularly because preclinical data support a correlation between the appearance of rash and concentration

please see the print version.

for these agents (Bruno, Mass, Jones, Lu, & Winer, 2003).

Some evidence suggests that the appearance of skin rash may

be useful as a marker of efficacy for HER1/EGFR-targeted agents. Several studies with erlotinib have demonstrated a relationship between severity of skin reaction and treatment efficacy. Phase II studies in NSCLC, head and neck cancer, and ovarian cancer sug-gest that survival rates are significantly increased in patients with skin reactions, compared to those without (Clark, Perez-Soler, Siu, Gordon, & Santabarbara, 2003; Perez-Soler et al., 2004). This observation was repeated in the pivotal phase III trial of erlotinib

Figure 1. Dermatologic Toxicities Secondary

monotherapy for NSCLC, in which the patients who developed

to Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

a rash (75%) survived significantly longer than those who did

not: 8.5 months for patients with grade 1 rash and 19.6 months

Note. From "Mechanisms of Cutaneous Toxicities to EGFR Inhibitors,"

for patients with grade 2 or 3 rash versus 1.5 months for patients

by M.E. Lacouture, 2006, Nature Reviews Cancer, 61(1), p. 804. Copy-

who did not develop any rash (p < 0.0001) (Perez-Soler, 2006).

right 2006 by Nature Publishing Group. Reprinted with permission.

Overall, these observations support the consensus that patients who develop rash should be treated for the reaction while being maintained on anti-HER1/EGFR therapy; those patients may ob-

(usually manifested as paronychia), and hair changes (usually

tain the greatest benefit from the drugs.

manifested as mild hair loss) (Lacouture, 2006; Segaert & Van Cutsem, 2005). These adverse events are observed during

pathobiology of Skin Reactions

treatment with all HER1/EGFR-targeted agents, MAbs, and TKIs, and their etiology suggests that such skin toxicities are

Associated With Human Epidermal

a class effect of HER1/EGFR-targeted therapies. However, dif-

Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors

ferences may exist in the incidence and manifestation of these events with different treatments.

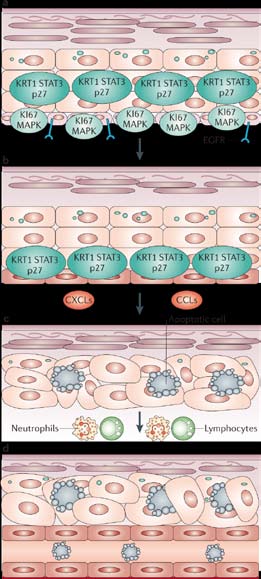

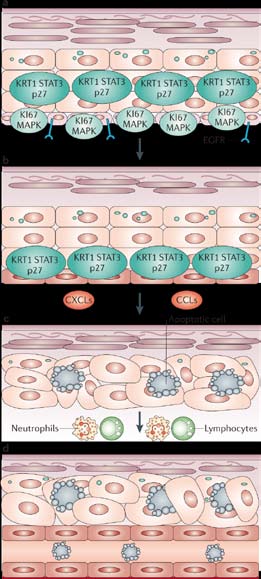

Although the pathobiology of HER1/EGFR-targeted inhibitor-

The papulopustular rash generally develops along a char-

associated skin reactions is not understood fully, drug-induced

acteristic course. Within the first week, patients experience

inhibition of the HER1/EGFR is believed to affect keratinocyte

a sensory disturbance on the face with erythema and edema,

proliferation, differentiation, migration, and attachment (Jost,

followed by a papulopustular eruption (in weeks 1–3). In

Kari, & Rodeck, 2000; Woodworth et al., 2005). HER1/EGFR is

week 4, a crusting of the rash develops. Provided that the rash

expressed in epidermal keratinocytes, sebaceous and eccrine

is treated successfully, patients may continue to experience

glands, and the epithelium of the hair follicle (Nanney, Sto-

erythema and dry skin in the areas previously affected by the

scheck, King, Underwood, & Holbrook, 1990). Such expression

papulopustular eruption.

is particularly high in proliferating and undifferentiated kerati-nocytes, which commonly are found in the basal and suprabasal

layers of the epidermis, and in the outer root sheath of the hair

Directly comparing the incidence of skin toxicities (and, in

follicle (Fox, 2006). Inhibition of the HER1/EGFR signaling

particular, rash) for different agents is challenging. Descriptive

pathway is believed to play a critical role in inflammatory cell

terms often differ in gradation schemes between trials, and in

recruitment and subsequent cutaneous injury, which can lead

some instances skin toxicities are recorded as a single event

to the development of dry skin, papulopustules, and periungual

(e.g., dermatitis), whereas in others, they may be broken down

inflammation (Lacouture, 2006). The potential effects of HER1/

into separate categories (e.g., rash, acne, dry skin).

EGFR inhibition in the skin are illustrated in Figure 2.

Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing • Volume 12, Number 2 • Managing Skin Reactions

Guidelines for the Treatment

of Skin Reactions Associated

With Human Epidermal Growth Factor

Inhibitors

As yet, no data from controlled clinical studies investigating

treatment options for HER1/EGFR-targeted inhibitor-associated skin reactions have been published; therefore, no peer-reviewed, evidence-based treatment recommendations are available. To date, proposed treatments are based mostly on qualitative rather than quantitative evidence (Lacouture, Basti, Patel, & Benson, 2006; Rhee et al., 2005). However, patients still require treatment and advice for skin reactions, and in the absence of suitable clini-cal data, best practice offers the best treatment advice.

The aim of the forum in Chicago was to bring a number of

experts together in an attempt to amalgamate their interdisci-plinary knowledge (published or otherwise) as well as to distill the common practices employed by their institutions into a consensus approach for the treatment of dermatologic adverse events associated with HER1/EGFR-targeted inhibitor therapy. Discussion at the forum focused primarily on the clinical man-agement of cutaneous toxicities; however, the experts also advocated a proactive approach for patients that could minimize the occurrence and severity of toxicities.

To view this image,

practical Guidelines for patients

please see the print version.

Two key patient education recommendations were made at the

forum: Patients should regularly use a thick, alcohol-free emollient for dry skin (alcohol can dry the skin). A number of recommended emollients are listed in Table 2. Application of high-sun protection factor (≥ 15) physical sunscreen (i.e., containing zinc oxide or tita-nium dioxide) each morning and prior to sun exposure is recom-mended for all patients receiving HER1/EGFR-targeted agents.

Based on the existing literature, a range of other practical

guidelines also might be considered to help prevent rash and

a. Normal expression of HER1/EGFR-dependent molecular markers. Be-

other cutaneous toxicities, which include the following (Herb-

fore treatment, the basal layer shows expression of phosphorylated

st, Fox, Viele, & Messner, 2006; O'Keeffe, Parrilli, & Lacouture,

HER1/EGFR, MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) and the prolif-

2006; People Living With Cancer, 2006).

eration marker KI67, and suprabasal expression of phopsphorylated

• Patients should take care to remain hydrated.

HER1/EGFR, the cyclin-dependent-kinase inhibitor p27, KRT1 (keratin

• Patients should ensure that they apply an adequate amount

1) and STAT3 (signal transducer and activator of transcription 3).

of sunscreen: more than half a teaspoon of sunscreen to

b. During HER1/EGFR inhibitor therapy, phosphorylated HER1/EGFR

each arm, the face, and neck, and a little more than one

is abolished in all epidermal cells and the expression of MAPK is

teaspoon to the chest and abdomen, back, and each leg. The

reduced. Inhibition of HER1/EGFR in basal keratinocytes leads to

use of a broad-brimmed hat also is advised if going outside.

growth arrest and premature differentiation, as demonstrated by upregulated p27 KIP1, KRT1 and STAT3 in the basal layer.

• Patients should avoid long, hot showers. Instead, patients

c. Subsequently, the release of inflammatory cell chemoattractants

should use lukewarm water and mild (preferably scent-free)

(such as CXCLs and CCLs) recruits leukocytes that release enzymes,

soap, ensuring that genital, rectal, and skin-fold areas are

causing apoptosis and tissue damage, with consequent apoptotic

cleaned thoroughly. A moisturizer should be applied within 15

keratinocytes and ectatic (dilated) vessels.

minutes of showering or bathing (to prevent skin drying).

d. A decrease in epidermal thickness is observed, with a thin stratum

• Patients should avoid laundry detergent with strong per-

corneum that lacks its characteristic basket weave configuration,

fumes and use only hypoallergenic makeup.

indicating abnormal differentiation.

• The use of saline nasal spray followed by petroleum jelly

may reduce risk of nosebleeds.

Figure 2. The Effects of Human Epidermal Growth

• Patients should use personal lubricant for intercourse.

Factor Receptor (HER1/EGFR) Inhibition in Skin

• To prevent nail problems, patients should keep finger and toe-

Note. From "Mechanisms of Cutaneous Toxicities to EGFR Inhibitors,"

nails clean and trimmed; avoid biting of nails, pushing back cu-

by M.E. Lacouture, 2006, Nature Reviews Cancer, 61(1), p. 806. Copy-

ticles, tearing the skin around the nail bed, or applying artificial

right 2006 by Nature Publishing Group. Reprinted with permission.

nails; and avoid tight-fitting shoes. Patients also are advised to

April 2008 • Volume 12, Number 2 • Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing

therapeutic decision making, forum attendees felt that a simple,

Table 2. Recommended Agents for Dry Skin,

more specific grading system would be the most appropriate rash

Itching, and Sun Exposure

associated with HER1/EGFR-targeted inhibitors. Thus, classifying skin reactions as mild, moderate, or severe was believed to be the

most effective system for assigning therapeutic intervention.

The following is a stepwise approach to intervention, employ-

• Vanicream® (Pharmaceutical Specialties, Inc.),

ing the suggested three-tiered grading system developed by the

Eucerin® (Beiersdorf AG), Aquaphor® (Beiersdorf

consensus group.

AG), Aveeno® (Johnson & Johnson Consumer Com-

panies, Inc.), and Cutemol® (Summers Laboratories

mild Skin Toxicity

Mild skin toxicity (papulopustular rash) is defined as generally

Exfoliants (for scaly areas)

localized, minimally symptomatic, with no sign of superinfection,

• Ammonium lactate12% (Am-Lactin®, Upsher-Smith

and no impact on daily activities. Some attendees suggested that,

Laboratories, Inc.) for body

in many instances, no intervention was necessary, whereas others

• Urea 20%–40% cream for palms, soles, and fissures

felt that intervention of either topical hydrocortisone (1% or 2.5%

cream) or clindamycin (1% gel) would be beneficial. Dose reduc-

• Body: Sarna Ultra® (PharmaDerm) cream and Re-

tion of the HER1/EGFR-targeted agent was not recommended.

genecare® (MPM Medical, Inc.) gel as needed

• Scalp: Fluocinonide 0.05% shampoo or clobetasol

moderate Skin Toxicity

Moderate rash is defined as papulopustules with mild pruritus

or tenderness, with minimal impact on activities of daily living

• Antihistamines (diphenhydramine 25–50 mg twice

and no signs of superinfection. The suggested therapeutic inter-

daily and/or cetirizine 10–20 mg per day)

vention is hydrocortisone (2.5% cream), clindamycin (1% gel), or

• Pregabalin (Lyrica®, Pfizer) 75–100 mg twice daily

pimecrolimus (Elidel®, Novartis) (1% cream), with the addition of

• Any broad-spectrum sunscreen containing zinc ox-

doxycycline (100 mg PO BID) or minocycline (100 mg PO BID)

ide or titanium dioxide

(Micantonio et al., 2005; Molinari, De Quatrebarbes, Andre, & Aractingi, 2005; Sapadin & Fleischmajer, 2006). Dose reduction of the HER1/EGFR-targeted agent was not recommended.

wear gloves when washing dishes or using chemical clean-ing agents. Hands and feet should be moisturized frequently;

Severe Skin Toxicity

petroleum jelly is particularly effective and should be applied to the skin around the nails periodically throughout the day.

Severe skin toxicity is defined as a rash that may be generalized

At night, applying a thick coat to hands and feet and covering

and accompanied by severe pruritus or tenderness; this level of

with white cotton gloves and socks may be helpful.

toxicity has a significant impact on activities of daily living and

• If a patient develops trichomegaly (i.e., excessive eyelash

has the potential for superinfection. The dose of the HER1/EGFR

growth) or eye complaints, the eyelashes should be trimmed

inhibitor should be reduced (according to the principal investiga-

and the patient should have an ophthalmologic consultation.

tor). The skin toxicity should be treated the same as for moderate

Most importantly, patients should be educated to call a health-

rash but with the addition of a methylprednisolone dose pack. In

care professional as soon as they develop any symptoms of

the event that severe rash symptoms fail to respond to the above-

cutaneous toxicity. Early intervention is critical in the clinical

mentioned interventions, interruption of the HER1/EGFRI-tar-

management of these events, so an early (< 14 days from EGFR-

geted therapy is recommended. However, treatment may resume

inhibitor therapy onset) follow-up is advisable.

(most likely at a lower dose) once skin reactions have diminished in severity at a recommended follow-up of two weeks.

clinical management

The use of pimecrolimus or tacrolimus (Protopic®, Astellas

Pharma, Inc.) for HER1/EGFR-associated skin reactions is being

The treatment algorithm presented in Figure 3 represents the

investigated at a number of institutions; however, it is an immu-

key output from the forum. The effective treatment of skin rashes

nosuppressant, which should be taken into account when con-

associated with HER1/EGFR-targeted inhibitors depends largely

sidering treatment options (Novartis, 2006). Although a causal

on accurate grading of skin reactions to allow for appropriate

relationship has not been established, rare cases of skin malig-

intervention. The National Cancer Institute (2006) Common

nancies and lymphoma have been observed in patients treated

Toxicity Criteria (NCI-CTC) is used most commonly to grade

with calcineurin inhibitors, such as pimecrolimus (Novartis).

adverse events in clinical trials with HER1/EGFR-targeted agents

Such incidences most likely are associated with long-term usage;

(see Table 3); it is designed, primarily, as a surveillance tool and

pimecrolimus is not recommended, however, in immunosup-

is of limited use as an aid to selecting intervention. Although cer-

presed patients (Novartis). As a result, great care should be

tain categories are relevant to events associated with HER1/EGFR

taken when considering its use in patients with cancer.

inhibitors, including rash and desquamation, they often are not sufficiently specific. For example, within the NCI-CTC, rash sever-

ity is based on body surface area coverage; this can be misleading because rash associated with HER1/EGFR inhibitors generally

The skin toxicities associated with HER1/EGFR-targeted

are confined to the face and upper trunk. For the purposes of

inhibitors can cause patients physical and psychological symp-

Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing • Volume 12, Number 2 • Managing Skin Reactions

• Employ a proactive approach in managing skin reactions.

• Suggest patients use a thick, alcohol-free emollient cream.

• Suggest patients use a sunscreen of SPF 15 or higher, preferably containing zinc oxide or titanium dioxide.

• If a patient presents with rash, verify appropriate administration and follow the proceeding algorithm in a step-wise manner.

Continue EGFR inhibitor at current dose and monitor for change in severity.

• Generally localized• Minimally symptomatic• No impact on ADL

Topical hydrocortisone 1% or 2.5% cream* and/or clindamycin 1% gel

• No sign of superinfection

Reassess after 2 weeks (either by healthcare professional or patient self-reported); if reactions worsen or do not improve, proceed to next step.

Continue EGFR inhibitor at current dose and monitor for change in severity; continue treatment of

• Mild symptoms (e.g.,

skin reaction with the following:

pruritus, tenderness)

• Minimal impact on ADL• No sign of superinfection

Hydrocortisone 2.5% cream* or Clindamycin 1% gel or pimecrolimus 1% cream PLUS doxycycline

100 mg BID or minocycline 100 mg BID

Reassess after 2 weeks (either by healthcare professional or patient self-reported); if reactions worsen or do not improve, proceed to next step.

Severe• Generalized• Severe symptoms (e.g.,

pruritus, tenderness)

Reduce EGFR-inhibitor dose as per label and monitor for change in severity; continue treatment of

• Significant impact on

skin reaction with the following:

• Potential for

Hydrocortisone 2.5% cream* or clindamycin 1% gel or pimecrolimus 1% cream PLUS doxycycline

100 mg BID or minocycline 100 mg BID PLUS medrol dose pack

Reassess after 2 weeks; if reactions worsen, dose interruption or discontinuation may be necessary.

* The use of topical steroids should be employed in a pulse manner based on your institution's guidelines.

ADL—activities of daily living; BID—twice daily; EGFR—epidermal growth factor receptor; SPF—sun protection factor

Figure 3. proposed Therapy Algorithm for the management of Skin Reaction Associated

With Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors

Note. From "Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitor–Associated Cutaneous Toxicities: An Evolving Paradigm in Clinical Management," by T.J. Lynch, Jr., E.S.

Kim, B. Eaby, J. Garey, D.P. West, and M.E. Lacouture," 2007, Oncologist, 12(5), p. 618. Copyright 2007 by AlphaMed Press. Reprinted with permission.

toms, particularly given that rash characteristically occurs

The algorithm suggested by the consensus group and pre-

on exposed areas such as the face. Although the concerns of

sented in this article represents current best practice for the

patients (and caregivers) must be addressed sympathetically,

treatment of rash associated with HER1/EGFR inhibitors. Con-

in most cases, these adverse events can be managed without

trolled studies remain necessary to fully evaluate the efficacy

the need for dose modification or interruption to the HER1/

of the strategies presented in the algorithm, but this approach

EGFR-inhibitor regimen. Moreover, in refractory cases, the

hopefully will be a useful guide for nurses and other healthcare

suspension of HER1/EGFR inhibitor therapy is temporary,

professionals, ensuring that patients receive the maximum pos-

allowing for appropriate intervention and diminution of skin-

sible clinical benefits from the continued and uninterrupted use

toxicity severity.

of the HER1/EGFR inhibitors.

April 2008 • Volume 12, Number 2 • Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing

Table 3. classification of Dermatologic Toxicities Associated With Human Epidermal Growth Factor

Receptor Inhibitors

Symptomatic, not interfering with Interfering with ADL

Discoloration, ridging, Partial or complete loss of nails;

Interfering with ADL

pain in nailbed(s)

Mild or localized

Intense or widespread

Intense or widespread and inter-

Macular or papular

Macular or papular eruption or

Severe, generalized erythro-

Generalized exfolia-

eruption or erythema

erythema with pruritus or other

derma or macular, papular, or

tive, ulcerative, or

without associated

associated symptoms; localized

vesicular eruption; desquamation bullous dermatitis

desquamation or other lesions

covering > 50% BSA

covering < 50% BSA

Intervention not

Intervention indicated

Associated with pain, disfigure-

ment, ulceration, or desquamation

Life threatening;

ADL—activities of daily living; BSA—body surface areaNote. From Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) [v.3.0], by National Cancer Institute, 2006. Retrieved February 20, 2008, from http://ctep.cancer.gov/forms/CTCAEv3.pdf. Adapted with permission.

The authors gratefully the participants of the October 2006 inter-

Greatens, T.M., Niehans, G.A., Rubins, J.B., Jessurun, J., Kratzke, R.A.,

disciplinary forum: Jean Pierre DeLord, Jody Gary, Giuseppe Giaccone,

Maddaus, M.A., et al. (1998). Do molecular markers predict survival

Patricia LoRusso, Thomas J. Lynch, Barbara Melosky, Martin Reck,

in non-small-cell lung cancer? American Journal of Respiratory

Roman Perez-Soler, Jennifer Temel, and Dennis P. West. The authors

and Critical Care Medicine, 157(4, Pt. 1), 1093–1097.

also acknowledge third-party medical writing support from Gardiner

Herbst, R., Fox, L.P., Viele, C.S., & Messner, M. (2006). Managing

Caldwell US, funded by Genentech, Inc., OSI Pharmaceuticals, Inc.,

rash and other skin reactions to targeted treatment. Retrieved

and F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

February 20, 2008, from http://www.cancercare.org/pdf/book-lets/ccc_managing_rash.pdf

Author contact: Beth Eaby, MSN, CRNP, OCN®, can be reached at eabyb@

Hoang, T., & Schiller, J.H. (2002). Advanced NSCLC: From cytotoxic

uphs.upenn.edu with copy to editor at [email protected].

systemic chemotherapy to molecularly targeted therapy. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy, 2(4), 393–401.

Jost, M., Kari, C., & Rodeck, U. (2000). The EGF receptor—An essen-

tial regulator of multiple epidermal functions. European Journal

Arteaga, C.L. (2001). The epidermal growth factor receptor: From mu-

of Dermatology, 10(7), 505–510.

tant oncogene in nonhuman cancers to therapeutic target in human

Kris, M.G., Natale, R.B., Herbst, R.S., Lynch, T.J., Jr., Prager, D., Be-

neoplasia. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 19(18, Suppl.), 32S–40S.

lani, C.P., et al. (2003). Efficacy of gefitinib, an inhibitor of the

Bruno, R., Mass, R.D., Jones, C., Lu, J., & Winer, E. (2003). Preliminary

epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase, in symptomatic

population pharmacokinetics (PPK) and exposure-safety (E-S) rela-

patients with non-small cell lung cancer: A randomized trial. JAMA,

tionships of erlotinib HCI in patients with metastatic breast cancer

(MBC) [Abstract 823]. Proceedings of the American Society of

Lacouture, M.E. (2006). Mechanisms of cutaneous toxicities to EGFR

Clinical Oncology, 22, 205.

inhibitors. Nature Reviews Cancer, 6(10), 803–812.

Clark, G.M., Perez-Soler, R., Siu, L., Gordon, A., & Santabarbara, P.

Lacouture, M.E., Basti, S., Patel, J., & Benson, A., III. (2006). The

(2003). Rash severity is predictive of increased survival with erlo-

SERIES clinic: An interdisciplinary approach to the management

tinib HCI [Abstract 786]. Proceedings of the American Society of

of toxicities of EGFR inhibitors. Journal of Supportive Oncology,

Clinical Oncology, 22, 196.

Cooke, T., Reeves, J., Lannigan, A., & Stanton, P. (2001). The value of

Micantonio, T., Fargnoli, M.C., Ricevuto, E., Ficorella, C., Marchetti,

the human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) as a prognos-

P., & Peris, K. (2005). Efficacy of treatment with tetracyclines to

tic marker. European Journal of Cancer, 37(Suppl. 1), S3–S10.

prevent acneiform eruption secondary to cetuximab therapy.

Fox, L.P. (2006). Pathology and management of dermatologic

Archives of Dermatology, 141(9), 1173–1174.

toxicities associated with anti-EGFR therapy. Oncology, 20(5,

Molinari, E., De Quatrebarbes, J., Andre, T., & Aractingi, S. (2005).

Suppl. 2), 26–34.

Cetuximab-induced acne. Dermatology, 211(4), 330–333.

Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing • Volume 12, Number 2 • Managing Skin Reactions

Nanney, L.B., Stoscheck, C.M., King, L.E., Jr., Underwood, R.A., &

Salomon, D.S., Brandt, R., Ciardiello, F., & Normanno, N. (1995).

Holbrook, K.A. (1990). Immunolocalization of epidermal growth

Epidermal growth factor-related peptides and their receptors in

factor receptors in normal developing human skin. Journal of

human malignancies. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology,

Investigative Dermatology, 94(6), 742–748.

National Cancer Institute. (2006). Common terminology criteria

Sapadin, A.N., & Fleischmajer, R. (2006). Tetracyclines: Nonantibiotic

for adverse events (CTCAE) [v.3.0]. Retrieved February 20, 2008,

properties and their clinical implications. Journal of the American

Academy of Dermatology, 54(2), 258–265.

Nicholson, R.I., Gee, J.M., & Harper, M.E. (2001). EGFR and cancer

Segaert, S., & Van Cutsem, E. (2005). Clinical signs, pathophysiology

prognosis. European Journal of Cancer, 37(Suppl. 4), S9–S15.

and management of skin toxicity during therapy with epidermal

Novartis. (2006). Elidel® (pimecrotimus) [Package insert]. Re-

growth factor receptor inhibitors. Annals of Oncology, 16(9),

trieved February 20, 2008, from http://www.pharma.us.novartis

Sipples, R. (2006). Common side effects of anti-EGFR therapy: Acne-

Ohsaki, Y., Tanno, S., Fujita, Y., Toyoshima, E., Fujiuchi, S., Nishigaki,

form rash. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 22(1, Suppl. 1), 28–34.

Y., et al. (2000). Epidermal growth factor receptor expression cor-

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2005). Patient information

relates with poor prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer patients

sheet gefitinib (marketed as Iressa). Retrieved February 20,

with p53 overexpression. Oncology Reports, 7(3), 603–607.

O'Keeffe, P., Parrilli, M., & Lacouture, M.E. (2006). Toxicity of targeted

therapy: Focus on rash and other dermatologic side effects. Oncol-

Woodworth, C.D., Michael, E., Marker, D., Allen, S., Smith, L., &

ogy Nurse Edition, 20(13), 1–6.

Nees, M. (2005). Inhibition of the epidermal growth factor recep-

People Living With Cancer. (2006). Skin reactions to targeted thera-

tor increases expression of genes that stimulate inflammation,

pies. Retrieved February 20, 2008, from http://www.plwc.org/

apoptosis, and cell attachment. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics,

Yarden, Y., & Sliwkowski, M.X. (2001). Untangling the ErbB signalling

Perez-Soler, R. (2006). Rash as a surrogate marker for efficacy of epi-

network. Nature Reviews, Molecular Cell Biology, 2(2), 127–137.

dermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in lung cancer. Clinical Lung Cancer, 8(Suppl. 1), S7–S14.

Perez-Soler, R., Chachoua, A., Hammond, L.A., Rowinsky, E.K., Huber-

Receive free continuing nursing education credit

man, M., Karp, D., et al. (2004). Determinants of tumor response

for reading this article and taking a brief quiz on-

and survival with erlotinib in patients with non-small-cell lung

line. To access the test for this and other articles,

cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 22(16), 3238–3247.

visit www.cjon.org, select "CE from CJON," and

Rhee, J., Oishi, K., Garey, J., & Kim, E. (2005). Management of rash

choose the test(s) you would like to take. You

and other toxicities in patients treated with epidermal growth fac-

will be prompted to enter your Oncology Nurs-

tor receptor-targeted agents. Clinical Colorectal Cancer, 5(Suppl.

ing Society profile username and password.

2), S101–S106.

April 2008 • Volume 12, Number 2 • Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing

Source: http://cincinnati.vc.ons.org/file_depot/0-10000000/0-10000/6741/associatedFiles/Eaby+Rash+Management+ArticleforVC.pdf

XYLAN & ARABINOXYLAN (100 Assays per Kit) or (1000 Microplate Assays per Kit) or (1300 Auto-Analyser Assays per Kit) © Megazyme International Ireland 2012 INTRODUCTION:In nature, D-xylose occurs mainly in the polysaccharide form as xylan, arabinoxylan, glucuronoarabinoxylan, xyloglucan and xylogalacturonan. Mixed linkage D-xylans are also found in certain seaweed species and a similar polysaccharide is thought to make up the backbone of psyllium gum. Free D-xylose is found in guava, pears, blackberries, loganberries, raspberries, aloe vera gel, kelp, echinacea, boswellia, broccoli, spinach, eggplant, peas, green beans, okra, cabbage and corn. In humans, D-xylose is used in an absorption test to help diagnose problems that prevent the small intestine from absorbing nutrients, vitamins and minerals in food. D-Xylose is normally easily absorbed by the intestine. When problems with absorption occur, D-xylose is not absorbed and blood and urine levels are low. A D-xylose test can help to determine the cause of a child's failure to gain weight, especially when the child seems to be eating enough food. If in a polysaccharide, the ratio of D-xylose to other sugars etc. is known, then the amount of the polysaccharide can be quantitated from this knowledge plus the determined concentration of D-xylose in an acid hydrolysate. Xylans are a major portion of the polysaccharides that could potentially be hydrolysed to fermentable sugar for biofuel production.

Fighting counterfeit phones Making communication easier UgANDA CoMMUNICATIoNS UCC LAUNCHED RURAL CoMMUNICATIoN CoMMISSIoN ADVISES oN HoW DEVELoPMENT FUND To BRIDgE THE To BUY gENUINE PHoNES P. 7 DIgITAL RURAL DIVIDE P. 3 Daily Monitor FRIDAY, MAY 30, 2014 www.monitor.co.ug Journal UGANDA DIGITAL MIGRATION DEADLINE June next year is the global deadline for replacing analogue with digital TV